Taiwan is a world leader when it comes to recycling the electronic devices and household appliances that its citizens throw away each year. Last year, according to the Environmental Protection Administration’s (EPA) Web site, the WEEE (waste electrical and electronic equipment, or e-waste) recycling rate reached a new high of 85.87 percent.

Only a few other countries, mostly in Northern Europe, recycle more than 70 percent of their e-waste. Because such items typically contain minute amounts of various metals, as well as glass and plastics, breaking them down into materials that can be reused is far more complex and expensive than recycling a cardboard box or an aluminum can.

Globally, more than 53 million metric tons of WEEE are generated each year, of which a mere 17 percent is recycled.

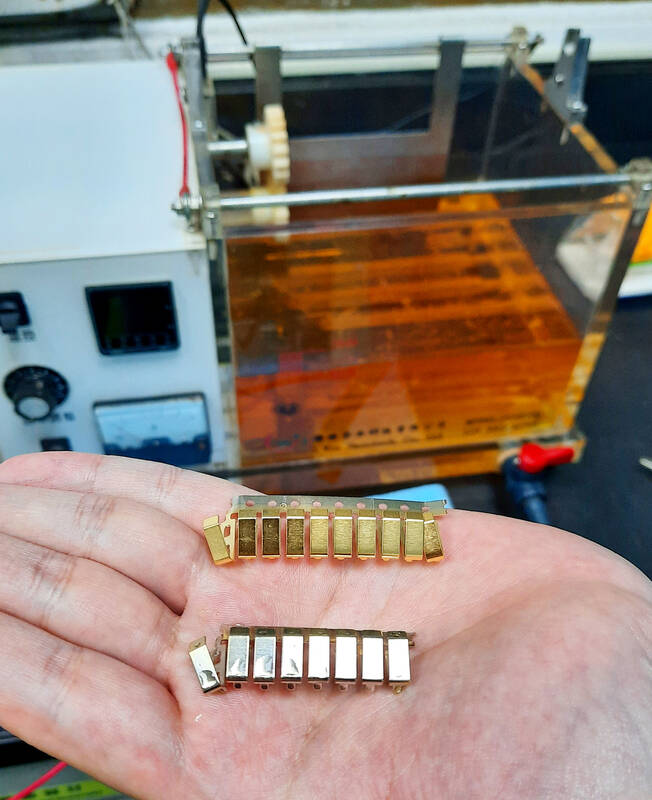

Photo: Steven Crook

‘BEST PRACTICES’

Thanks to certification and licensing requirements, informal recycling — in which unwanted toxic elements are often disposed of irresponsibly — is a thing of the past in Taiwan.

“The authorities here have been very smart, not merely learning from the EU, but looking worldwide to find international best practices,” says Armin Ibitz, an associate professor at Wenzao Ursuline University of Languages who’s written about e-waste recycling and the circular economy.

Photo: Steven Crook

Ibitz, director of the Wenzao EU Center and chair of the university’s Graduate Institute of European Studies, explains that under Taiwan’s 4-in-1 Recycling Program, manufacturers and importers of six types of electrical and electronic goods are obliged to pay into a recycling fund supervised by the EPA. That money is then distributed to incentivize proper recycling.

The six categories are IT equipment (such as laptops, motherboards, keyboards, monitors, and printers), TVs, refrigerators, washing machines, air-conditioning units and fans. Mobile phones aren’t included.

Taiwan’s impressive recycling rate doesn’t, however, mean that discarded electronics are handled in the best possible way, or even that they’re fully processed here in Taiwan.

Photo: Steven Crook

For years, regulations made it impossible for local innovators like UWin Nanotech Co Ltd to apply their green-chemistry technologies within the country. The New Taipei City-based company, which has invented solutions that strip valuable metals from printed circuit boards (PCBs) and other types of e-waste without producing toxic wastewater, has customers in 30 countries, including China and the US.

In 2019, when UWin established an e-waste recycling plant in Japan’s Chiba Prefecture, UWin President Kenny Hsu (許景翔) told the media that, compared to traditional recycling methods, his company’s processes are cheaper and yield metals with higher purity levels.

As UWin Vice President Leo Chang (張永撙) explains, until recently PCBs had to be shredded in order to qualify for recycling subsidies. This requirement was put in place to prevent double dipping. If a piece of e-waste is left intact, an unscrupulous businessperson could report it as “recycled,” but later pretend it had just been collected, and claim a second subsidy.

Photo courtesy UWin Nanotech

In Chang’s opinion, without a subsidy system, “the situation here would be like that in Malaysia, where recyclers depend on market demand for precious metals,” and where less valuable materials are often landfilled or incinerated with ordinary waste.

According to earth.org, if e-waste ends up in a landfill, “the surrounding soil can become contaminated with toxic substances such as mercury, cadmium, beryllium and lead. These chemicals enter the soil, waterways and air, leading to polluted environments and negatively impacting human and marine life.”

Chang describes the EPA’s revision of the rules, so that non-shredded e-waste is eligible for recycling subsidies, as “a big breakthrough.” UWin is putting the finishing touches to a brand-new facility in Taoyuan at which it’ll recycle lithium-cadmium batteries using methods refined and patented by Hsu, the company’s founder. (A future article will cover battery recycling in depth.)

Standard e-waste recycling involves dismantling by hand or robot, crushing, and then extracting metals through hydrometallurgy or pyrometallurgy or both.

Only a handful of smelters around the world, and none in Taiwan, are ideal for processing WEEE. In addition to requiring a great deal of energy, pyrometallurgical treatment has to be followed by hydrometallurgical processes to separate the various metals.

There’s another problem with shredding: PCB waste isn’t always properly disposed of. Between 2016 and 2019, 2,286 metric tons of fiberglass powder from ground-up boards was dumped in a rural part of Pingtung County. Samples from the site revealed dangerously high levels of copper.

UWin’s low-carbon hydrometallurgy technologies not only make it possible to completely recycle e-waste within Taiwan, rather than sending shredded PCBs and crushed batteries abroad, but are also so safe there’s no need to wear gloves. While showing how the UW-700 solution can be used to remove gold from components, Chang demonstrates this by dipping his hand in the yellowish liquid.

“We can handle 37 metals on the periodic table,” Chang says. He expresses confidence that rhodium — a metal far more expensive than gold — will be added to that list in the near future.

According to UWin’s Web site, one metric ton of waste PCBs can yield metals worth approximately NT$84,000. For a metric ton of recycled iPhone 10 handsets, the yield might exceed NT$1.18 million.

INTERNATIONAL PRESSURE

Wenzao University’s Ibitz says that Taiwan could do a lot more to reduce the volume of e-waste.

He supports EU measures which aim to ensure that more products are repaired rather than replaced within their guarantee period, and that consumers have easier and cheaper options to fix products that are technically repairable once the guarantee has expired (“the right to repair”).

“Taiwan has a key role in designing and manufacturing many of these products. But instead of using their influence to change things for the better, companies here only respond to outside pressure when they don’t have a choice,” he says.

If Taiwanese manufacturers want to sell IT products and components in Europe, for instance, they have to adhere to EU rules such as the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive, which limits the use of certain materials in electrical and electronic equipment. Cadmium, lead and mercury are among the 10 controlled substances.

“Local second-hand markets are weak. It seems Southeast Asian workers are the only people who buy second-hand smartphones in Taiwan,” says Ibitz, who says that every cellphone he’s ever owned was a hand-me-down.

Ibitz says that in his native Austria, for some items citizens have to pay a small fee if they bring more than a certain weight of recyclables to a municipal disposal facility. In Taiwan, by contrast, it’s often possible to sell larger devices and appliances to private recycling businesses. The latter is an incentive to recycle, he says, whereas the former encourages people to keep broken-down items at home — or worse, dump them in the countryside.

When he was a child, it wasn’t unusual for Austrians to discard dead appliances in landfills or even woodlands, Ibitz recalls. It’s far less common nowadays, in part because people know better.

Stressing the importance of education, he says that “Taiwanese are open to change and they’re willing to change.” Compared to several years ago, far more students now want to take his environment and sustainability courses. People are increasingly familiar with the concepts of ESG (environmental, social, and governance criteria for companies) and SDGs (the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals), he adds.

Yet, he laments, “environmental knowledge is quite high, but environmental behavior lags some way behind. So many of my students come to class with a drink in a single-use plastic bottle.”

Steven Crook, the author or co-author of four books about Taiwan, has been following environmental issues since he arrived in the country in 1991. He drives a hybrid and carries his own chopsticks. The views expressed here are his own.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades