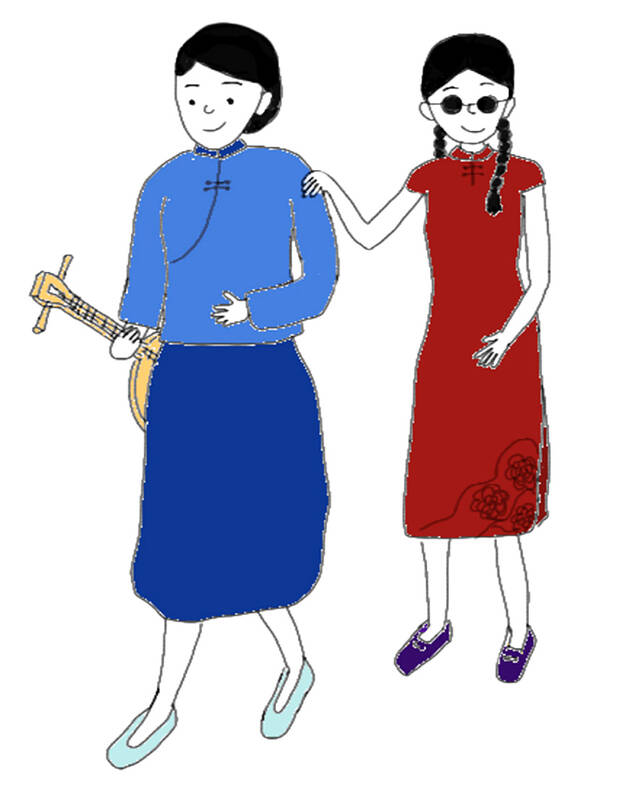

During the late 1940s, two blind teenage girls could be seen walking with their moon lutes from Badu (八堵) to Keelung (基隆). Accompanied by a guide, they sometimes trekked more than 10km to Heping Island (和平島), then a bustling commercial hub with many opportunities to perform liam-kua (唸歌), a traditional form of melodic storytelling that mixes singing with the spoken word.

The duo kept singing on the journey home, and were often invited by locals who heard them to perform a set or two. By the time they got home in the wee hours, the nearby ditch that people bathed and washed their laundry in would be relatively clean, and they fetched drinking water for the next day.

The older girl, Hsiao Chin-feng (蕭金鳳), stopped performing after she got married. But the younger one, Yang Hsiu-ching (楊秀卿), carried on for more than seven decades and was revered as a national treasure when she died on June 17 last year at the age of 88.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

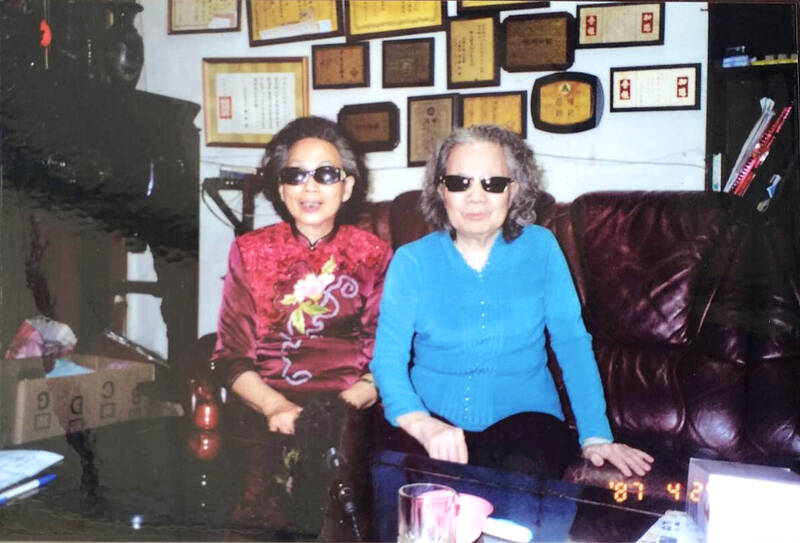

Yang Hsiu-ching played for most of her career alongside her husband Yang Tsai-hsing (楊再興), a train mechanic who learned how to play the daguangxian (大廣弦, an erhu-like bowed instrument) to take the stage with her during their years traveling the country and using liam-kua performances to peddle medicine and ointments.

Yang Hsiu-ching is known for pioneering the “dialogue” (口白) style of liam-kua, which emphasizes the spoken part through dialogue and dramatic narration, which helped maintain interest in the art form during the 1960s and 1970s when modern or Western forms of entertainment began to gain popularity.

After concluding a successful 20-year radio career in 1989, she continued to perform well into old age. Today, younger people probably recognize Yang Hsiu-ching for her role as narrator in the acclaimed 2017 film The Bold, the Corrupt and the Beautiful (血觀音).

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank

ROUGH BEGINNINGS

Yang was born in 1934 in Quchi (屈尺) in today’s Sindian District, but the family moved to Jiufen (九份) at a young age. She caught a fever at the age of four and, due to delayed treatment, her vision was severely impaired. By the time her stepfather carried her on foot for a whole day to a well known eye doctor in Sansia (三峽), she was already blind.

Becoming a musician was one of the ways for blind people to make a living, and at the age of seven, Yang was given to successful blind liam-kua singer Chiu Feng-ying (邱鳳英) as a foster daughter. She didn’t get along with her new family, and after one particularly intense argument with her foster parents, Yang was sent home.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank

A few years later, her stepfather saw a woman named Hsiao-Chen A-hsien (蕭陳阿現) performing with a blind young girl at Badu Railway Station. He asked if Hsiao-Chen could take Yang as a disciple, but Hsiao-Chen said the only way was for Yang to become her foster daughter, writes Chen Yi-kai (陳奕愷) in an oral history book about traditional performers.

They lived in an old house without tap water between two railroads, and were mocked by neighbors for drinking from the nearby ditch. Hsiao-Chen’s life was also hard — as a child, she was given to a family as a future daughter-in-law, but her husband abandoned her during World War II and left her to care for two children in addition to his young brother.

Hsiao-Chen did all sorts of odd jobs, working so much that one day she collapsed and could no longer care for the children. While recovering, she supplemented her income by guiding blind liam-kua singers, learning how to perform from watching and practicing on her own. With no close family, raising foster daughters and training them to perform was a way to ensure that someone took care of her in old age.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank

STRICT TRAINING

Hsiao-Chen was already training another blind foster daughter, Hsiao Chin-feng, when Yang arrived. Hsiao was five or six years older, and patiently taught Yang the basics. The hardest part was memorizing lyrics since the two couldn’t see, and they relied on other people reading the lyrics to them. They only heard the songs once and had little time to practice before they were asked to recite them, and were beaten for any errors.

Besides eating, sleeping and practicing her instrument, Yang recalls that she devoted all her time to memorizing lyrics. She was constantly reciting them, and passersby sometimes thought she had lost her mind. Through this training, she developed an uncanny ability to memorize, improvise and modify lyrics at will.

But she also attributes her memory to a strange event that occurred when she was 14 years old. That year, her leg suddenly swelled up to the point that it required surgery, leaving her with a permanent limp. But after this event, she says her memory became superb and was rarely beaten again.

Yang and Hsiao performed together on the street, at restaurants, banquet halls, tea shops, temple ceremonies and private residences. It was a rare sight as liam-kua was usually a solo act. They sang in unison, took turns and also harmonized, creating a new form of the performance. After Hsiao’s marriage, Yang continued on her own until she turned 18. It was 1951, and many of the establishments they frequented were taken over by refugees of the Chinese Civil War, who couldn’t understand or appreciate liam-kua.

With fewer and fewer opportunities to perform, Yang began working with ointment vendors to help peddle their wares. She would sing a set first to attract an audience, then suddenly stop at a crucial part of the story. The vendor would then appear and start advertising his products, and since the audience were eager to hear the rest of the tale, they stayed and listened. Often they ended up buying from him.

LIFELONG COMPANION

Yang was quite successful and did this for four more years until she met her husband. Yang Tsai-hsing was deeply impressed by Yang Hsiu-ching’s singing, and eventually quit his job to travel with her and help sell ointment. After they had children, they began selling ointment and other medicines themselves, traveling all over the countryside.

One time, a local hoodlum mocked Yang Tsai-hsing for sitting around while his wife performed.

“How about you go learn a bowed instrument so you could accompany her? It’ll probably sound even better,” he said.

Yang Tsai-hsing thought this was a great idea, and a week later he was on stage playing the daguangxian with his wife. They played together for more than 50 years.

The Yangs’ first foray into radio came in 1959, when a Taiwanese opera troupe leader hired them to record liam-kua for a local station. They spent six hours per day recording, then took on other jobs at night. This opportunity only lasted a year.

By the 1960s, Yang Hsiu-ching realized that she needed to modify her act to keep the public’s waning interest in liam-kua. The variations of tunes she could perform were limited, so she decided to elaborate on the spoken part, creating a new form of liam-kua that emphasized storytelling and entertainment value.

The pair stopped traveling for their children’s sake in 1968, and began working full time for various radio stations. It was a new challenge, as they could perform the same tunes in different stops on the road but had to come up with something different every day for the station.

The Yangs retired from radio in 1989. Yang Tsai-hsing died in 2008, but Yang Hsiu-ching was still teaching and playing well into her 80s, regaining fame as society developed a renewed interest in traditional Taiwanese arts. She won the National Culture Award one year before her death in 2021.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

What does the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) in the Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) era stand for? What sets it apart from their allies, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)? With some shifts in tone and emphasis, the KMT’s stances have not changed significantly since the late 2000s and the era of former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). The Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) current platform formed in the mid-2010s under the guidance of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and current President William Lai (賴清德) campaigned on continuity. Though their ideological stances may be a bit stale, they have the advantage of being broadly understood by the voters.