In the pale dawn light, a line of men solemnly stream into a mountain tunnel, with full bellies but heavy hearts. After enjoying breakfast with their family, they had set out once again for the underground work that could one day, without warning, claim their lives.

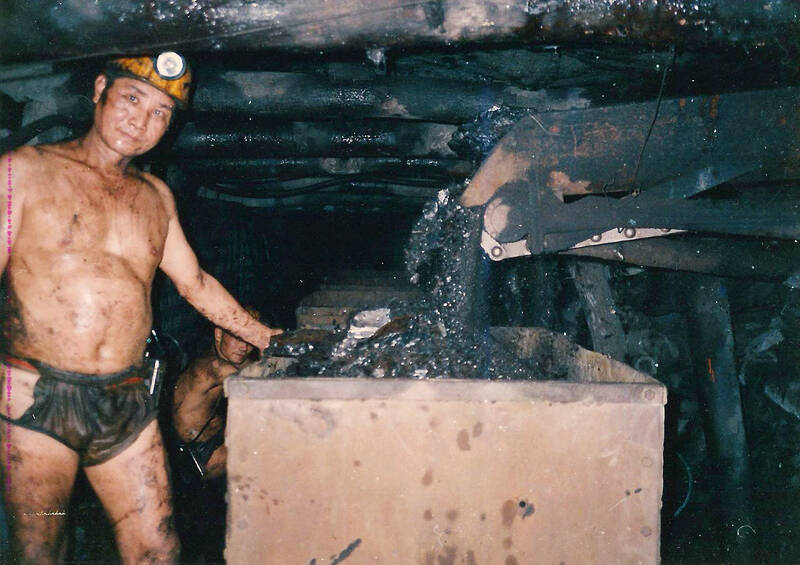

All day long, cartload after cartload of black gold is pulled out from this tunnel until midafternoon, when men begin to stream out again. They are black from head to toe, sweaty and exhausted. Their bellies are empty but their hearts are now full, for they have cheated death in the coal mine for one more day and can now return home with a few dollars in their pockets.

Such is the impression of a day in the life of a Taiwanese coal miner that one gains when visiting the Houtong Miner’s Culture & History Museum (猴硐礦工文史館) in New Taipei City’s Ruifang District (瑞芳). The stories and artifacts here are especially vivid and undeniably authentic as they are presented by retired coal miners themselves. They poured their blood, sweat and tears into this place, both literally when they worked underground here from the 1960s to 1980s, and now figuratively in the superb museum they have created from scratch in just four years, using money from their own meager pensions.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

The miners feel that the government has long neglected this important chapter of Taiwanese history, and with the last generation of miners now past middle age, their stories will soon fade away without a concerted effort at preservation. The industry barely gets a mention in the education system, despite the central role it played in Taiwan’s rapid economic development. For decades, coal was indispensable to Taiwan’s national defense, transportation, industry and even home life, but these economic benefits came at the cost of disease, injury and death to countless miners.

The founders of the museum hope that as everyone enjoys the benefits of Taiwan’s prosperity, these sacrifices will not be forgotten.

MOST PRODUCTIVE MINE

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

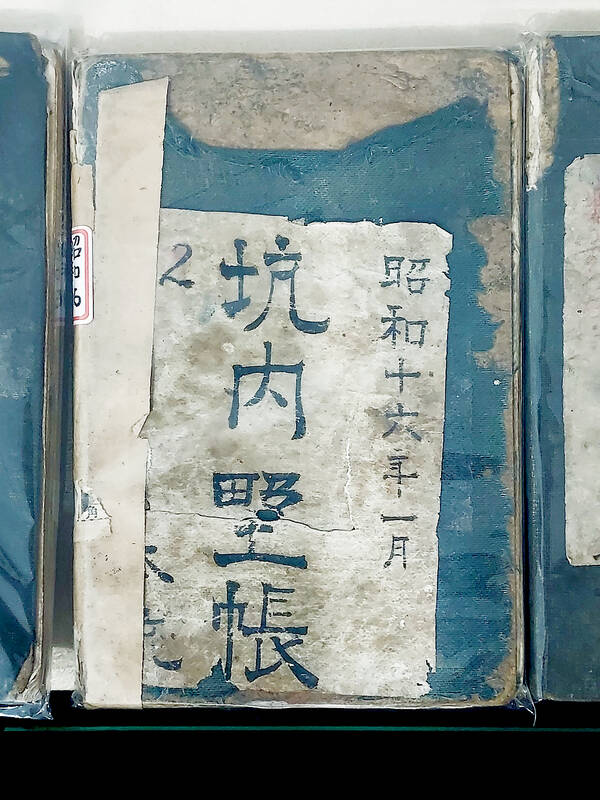

The museum is in the former offices of the Ruisan Mining Company (瑞三煤礦), right next to the entrance to the company’s “original mine,” one of many they operated. This particular mine was the most productive of Taiwan’s 394 coal mines, due in part to its size. It stretches horizontally for 6km, nearly to the famous Shifen Waterfall (十分), and downward nearly half a kilometer. The total length of coal cart tracks laid down in the shafts here totals 300km, and this still does not include the length of all the drifts reaching out from either side of these tracks where the coal was actually excavated.

This mine began operations in 1930 and was taken over by the newly formed Ruisan company in 1934. Starting as early as the 1960s, energy demands in Taiwan began to shift away from coal toward petroleum, but coal mines were still profitable.

Domestic coal later helped soften the effects of the energy crises of the 1970s. By the mid-1980s, however, the price of imported coal dropped below that of domestic coal. This and a series of mining accidents that killed 289 people in a single year finally sounded the death knell for the industry, and Ruisan ceased all operations in 1990.

Photo courtesy of Chou Chao-nan

HAZARDS OF MINING LIFE

Accidents were a common occurrence in the early days of mining in Taiwan. The death rate for coal miners was an astounding 12 percent, while the injury rate was around 800 percent, meaning that every miner was nearly certain to be injured multiple times throughout his or her career.

Major mining accidents were mostly of two kinds: collapses and explosions. The former were more common, but only affected one or two people at a time, while the latter happened less often but had the potential to kill dozens all at once.

Photo courtesy of Chou Chao-nan

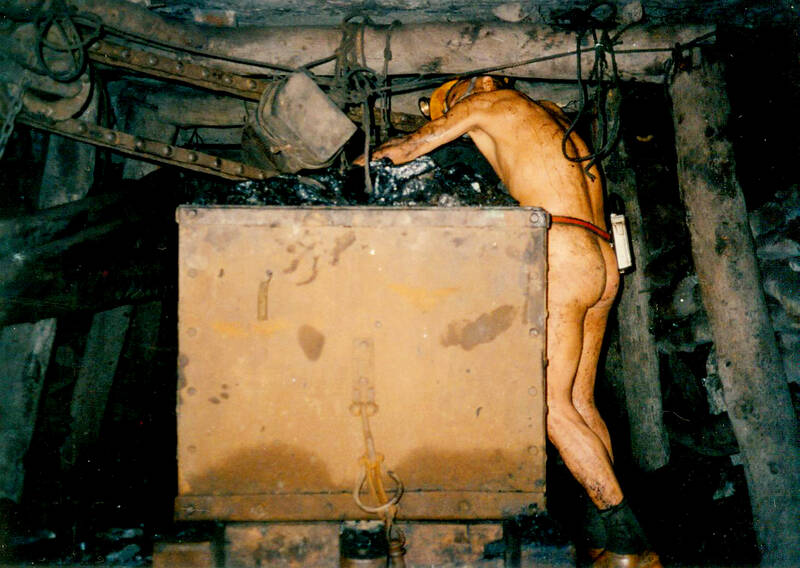

The coal veins here are only 30–60cm high, so the drifts were never cut very high, and miners often had to lie on their backs or sides to excavate the thin vein of coal. After every meter or so, they had to install supports made of acacia timber to prevent the roof from collapsing on them as they continued to extend the drift. Nevertheless, the sound of cracking wood was an all too familiar sound in the mines, and one everyone dreaded, as it announced the imminent collapse of one of the drifts.

An explosion could claim many more lives, as an entire section of the mine shaft turned into a giant pipe bomb. Methane released from coal veins or airborne coal dust, in sufficient concentrations, could be instantly ignited by a spark or heat source. Special detectors for these airborne hazards were used in the mines and are now on display in the museum, but accidents still occurred.

Coal dust that didn’t kill miners instantly through an explosion still posed a health risk in the form of pneumoconiosis. This lung disease is brought on by prolonged exposure to coal dust. There is no cure or treatment, and symptoms can continue to worsen even after a person has stopped working in the mines.

Photo courtesy of Chou Chao-nan

Japan was not a signatory to the Underground Work (Women) Convention, 1935, which prohibited women from working in coal mines, so dozens of women once worked in the Ruisan mines, doing the same manual labor as the men. The Republic of China did ratify this convention, but women still continued working in the mines here after the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) takeover.

As is common in Taiwan, rules aren’t always enforced until there is a problem. In 1963, a major accident caused the deaths of several married couples, turning their children into orphans overnight. The next year, urged on by then-first lady Soong Mei-ling (宋美齡), women were officially prohibited from underground mining work.

MUSEUM WITH A PERSONAL TOUCH

Photo courtesy of Chou Chao-nan

To reach the museum, walk south from Houtong Railway Station about 800m until you reach the end of the drivable road. Go through the underpass below the railway tracks on the right and continue straight to the museum. It is open every day except Monday, and staff are available for tours or to answer any questions, all free of charge. The miners are eager to share their stories with interested visitors.

The majority of the artifacts on display here were collected over the years by one of the museum’s founders, Chou Chao-nan (周朝南), who worked as a miner for over 30 years, starting at the age of 14. Even more impressive are the photographs on display, mostly taken by Chou himself. Decades ago, he took a camera into the mines to show others the cramped, filthy conditions of the coal drifts, and the stifling underground temperatures that caused most miners to work nearly or fully naked.

An even more personal touch is a trophy, which Chou and his coworkers were awarded by Ruisan for excavating the most coal of any team that year. For that year of hard work risking their lives to boost the company’s profits, they were awarded a bonus of NT$2,000.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

The museum also holds “Mining Life Memory Tours” (礦工生活記憶漫遊) several times per month (Chinese only, no charge). These are half-day walking trips covering several important mining operation sites in the Houtong area, guided by former miners.

This is your chance to learn more about the entire mining process and hear a firsthand account of what it was like to work here. Registration for this tour is done through their Facebook page, and all the tour dates for a given month are usually announced in the middle of the previous month.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them