“Formosa in the 19th century was responsible for some of the most lurid pages in the history of the Far East,” wrote George Carrington in his 19th century PhD thesis, Foreigners in Formosa, 1841-1871. Chief among them was the sordid tale of the ships Ann and Nerbudda, wrecked off the coast of Taiwan (then known as Formosa, or “beautiful island”) during the First Opium War (1839-1942) between the Qing Dynasty and British Empire.

At the time Formosa was seen as a possible alternative market for the British opium trade. In 1837, William Jardine, co-founder of Jardine, Matheson and Co wrote: “The drug market is getting worse every day owing to the extreme vigilance of the authorities. The only thing to do is to send more armed European ships along the coast and try out new markets such as Formosa.”

Jardine advocated annexing Formosa and said that the English merchant community in China all supported such a move.

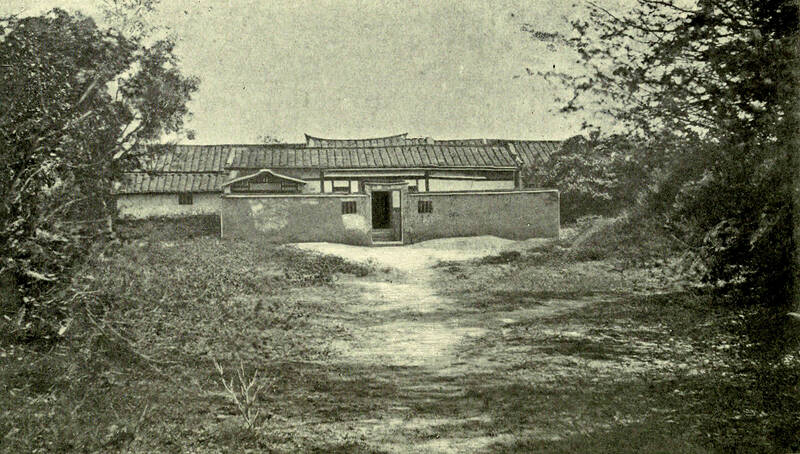

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Echoing Jardine in 1840, as the Opium War entered its opening stages, the cartographer and linguist William Huttmann, one of those fascinating omni-talented people the British Empire minted like penny coins, wrote to foreign secretary Lord Palmerston arguing that the British should occupy the east coast of Formosa. He said that a base there would enable the British to “constantly harass the Chinese by land, and destroy their foreign and coasting trade by sea.”

To be seen as a font of disorder on the margins of great imperial states is a terrible calamity for a place. Just as Taiwan is today.

THE NERBUDDA

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Nerbudda left Hong Kong bound for Zhoushan in September of 1841. Aboard were 274 souls, including 243 Indians, sailors and their followers. The ship was dismasted in a storm, and drifting, hit a reef off Keelung. The Europeans, including the crew, quickly abandoned the ship, leaving “the Indians… to their fate,” Carrington records with obvious disgust.

The stricken ship then drifted into Keelung Harbor where it remained for several days. The Indians made rafts and attempted to float to shore. Some drowned, some were killed for their belongings when they reached shore, but roughly two-thirds made it and were captured by the local government. They were marched overland to Tainan.

In Tainan the Indians were imprisoned. Meanwhile, the Europeans in the rowboat drifted over to the east coast where a passing ship picked them up and took them to Hong Kong.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In October, a British sloop, the Nimrod, arrived in Keelung looking for survivors, offer $100 for each one. After learning that the survivors had been packed off to Tainan, the captain had the ship bombard the harbor. Not much of a diplomat was he.

THE ANN

In March of 1842, the Ann set off for Macao from Zhoushan, with 57 aboard, again mostly Indian sailors. She was buffeted by strong winds and forced into Daan Harbor in Taichung. The crew seized a couple of local junks and attempted to leave, but were surrounded and captured by locals after an armed standoff.

One of the men aboard the Ann, Robert Gully, left a diary of his experiences. From time to time they were taken out of their cramped, waterless cells (“our jailer was the most wicked brute ever created,” he averred) and moved about.

On one such journey, he observed: “The houses, together with every building we passed, were formed of the before-mentioned boulders and mud, with, in many instances, a large wide-spreading tree or trees with seats close to them,” a tradition that continues in Taiwan to this day.

“The country had a most wild and heavy aspect,” he continued “more so than any I ever saw, and I began to think ‘Formosa’ a sad misnomer.”

In both cases, the local Manchu Brigade General Dahonga (達洪阿) and Han official Yao Ying (姚瑩) reported to the Emperor claiming to have sunk the ships and captured the foreigners in the act of attacking Taiwan. The diary of Captain Denham of the Ann states that their interrogators tried to force them to say the Ann was a warship, and that two of the captured men from his ship were repeatedly whipped when they refused.

The two local leaders then asked the emperor for permission to execute the men as invaders. That came down in May of 1842, in revenge for a British victory in the war. The emperor ordered the leaders imprisoned, but the others to be executed.

A SAD FATE

The Chinese Repository, a periodical published between 1832 and 1851 for Protestant missionaries, tells the sad tale of their fate.

“On or about Aug. 13, 1842, one hundred and ninety-seven men, late of the British vessels the Ann and Nerbudda, were placed on their knees near to each other, their feet in irons and their hands manacled behind their backs.”

This was done in a large field just outside Tainan, with thousands of local onlookers. Executioners then proceeded to behead all 197. The heads were tossed into baskets to be displayed on the shore, while the bodies were thrown into a mass grave.

Later, according to reports of the time, in discussions with a British representative, Yao Ying denied that any British people had been killed, arguing that only 130 “black ones” had been killed.

In October of 1842, the British ship Serpent arrived in Taiwan, knowing that the executions had taken place, but still searching for survivors. They were able to rescue survivors from another shipwreck, who had been well treated.

The Nerbudda Incident could have served as a useful excuse for a British attempt to occupy Formosa, an interest that would again be stimulated by the discovery of coal in the north, and would wax and wane as the century wore on.

The British desire for coal was confounded, however, by two factors. First, it was still cheaper to ship coal from Hong Kong; second, the local gentry in Keelung blocked coal excavations in the hills above the city, on the grounds that mining works wrecked the fengshui (風水).

After Tamshui was opened as a Treaty Port in the wake of the Arrow War, a bizarre private Prussian-British initiative to erect a colony near Yilan County’s Suao took place in 1868. By early 1869, its leader, James Horn, had built a fortress and was levying taxes on the local indigenous communities, infuriating China’s Manchu leadership (recall that James Brooke, the first white Rajah of Sarawak, had just died after 27 years of rule, and the reader can imagine what Horn might have been dreaming).

James Milisch, the German merchant funding the colony, arrived and encouraged Horn to grow tea. In the interest of good relations with the Qing Dynasty, the British suppressed the colony later that year, and Horn’s dreams were lost with him at sea off the southern tip of Taiwan.

British interest in Taiwan in the mid 19th century remains just another of the numerous might-have-beens that populate Taiwan history.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In