March 13 to March 19

As editor-in-chief of the pro-communist Kuangming News (光明報), Lu He-ruo (呂赫若) became a wanted man after the newspaper was raided by the authorities in August 1949. While many of his friends were arrested and executed, he managed to elude capture by hiding in the mountains of today’s New Taipei City’s Shihding District (石碇).

Lu never made it out of the mountains, and his death remained a mystery for decades. Today, it’s believed that the author, journalist, musician and playwright once dubbed “Taiwan’s number one talent” (台灣第一才子) died in September 1950 after being bitten by a poisonous snake. He was just 36 years old.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan Literature

Lu was critical of both the Japanese and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regimes, and his first story Oxcart (牛車) depicted how the colonial government took control of Taiwan’s sugar and rice industry and colluded with corporations to cause great suffering to local farming communities. It was one of three local pieces translated into Chinese and published in China in 1936, which was a first for Taiwanese literature.

Although he wrote primarily in Japanese, Lu refused to shift to patriotic or imperialistic literature during World War II. After witnessing the misrule of the KMT and the brutal suppression of the 228 Incident, he joined the Chinese Communist Party, which led to his early demise.

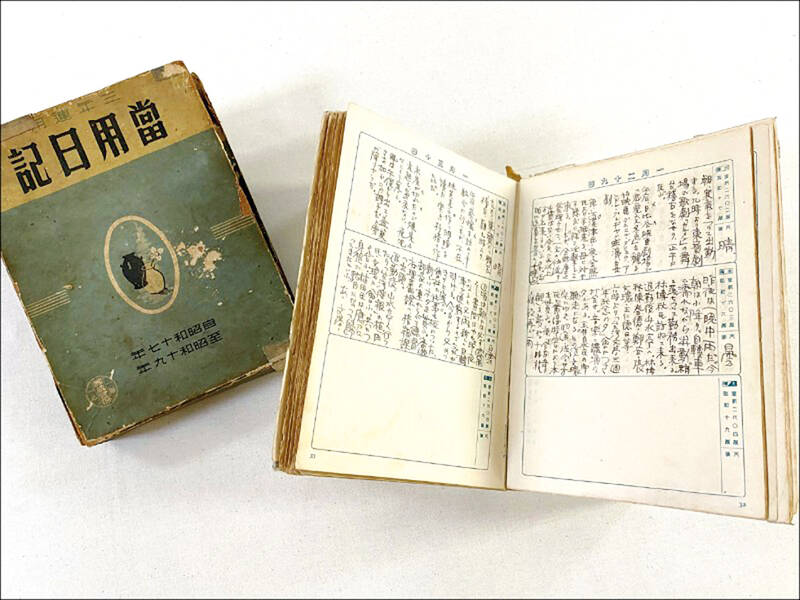

Lu’s stories ran in literary publications and newspapers, and during his life he only published one book, the short story collection Clear Autumn (清秋). Hitting the shelves on March 17, 1944, it was the first Japanese-language literary collection by a Taiwanese author.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan Literature

Due to the political climate, Lu’s works were buried for decades until Oxcart was republished in 1979. In 1995, his former student Lin Chih-chieh (林至潔) published an anthology containing 26 stories. Several more books on Lu have appeared since then, the latest an updated complete works collection by Ink Publishing (印刻), released on Wednesday last week.

HUMANITARIAN

Although Lu’s parents were wealthy, he believed in the “spirit of helping” and mostly wrote realist pieces highlighting social issues as well as the plight of the disadvantaged.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lin Ming-te (林明德) writes in the book Study of Lu He-ruo’s Works (呂赫若作品研究) that his pieces contain four main themes: Farmer and laborer rights, the condition of women, family conflict and current affairs.

Literary critic Yoshihiko Kawano wrote of Clear Autumn: “Through these stories, we can clearly feel the author’s intense criticism of society. This stems from the author’s humanitarian spirit, and furthermore, we can feel his love. He’s angry because he loves, sometimes to the point of wailing in dismay. He fixates on families and unfortunate people, and he doesn’t try to search for the tiny moments of happiness, instead insisting on uncovering their hardships.”

Lu was born in 1914 to a family of landowners in Fengyuan, Taichung. Growing up, he was influenced by the leftist and peasant’s rights movements of the 1920s, which inspired him to pay attention to the conditions of ordinary people.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan Literature

He wrote Oxcart at the age of 22, when he was teaching at Hsinchu’s Emei Elementary School (峨眉國小). The story is a tragic tale of an honest rural couple who were forced into a life of crime and conflict after losing their means of making a living.

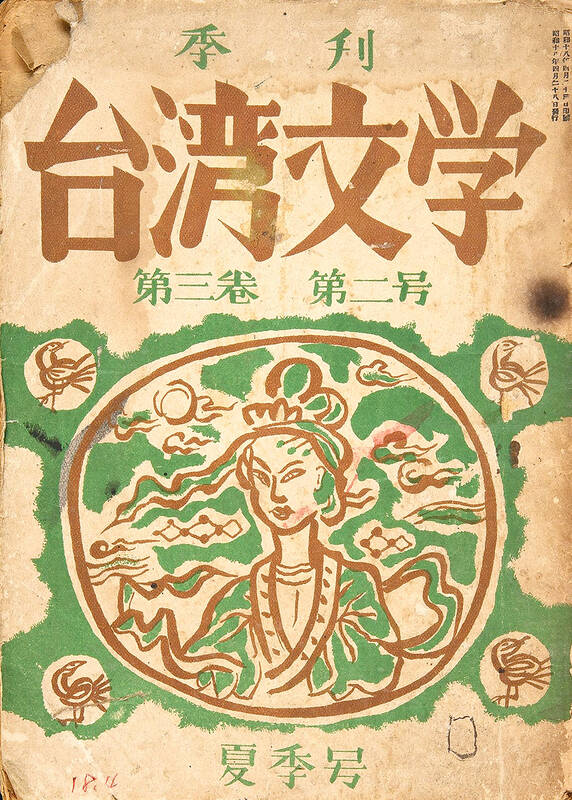

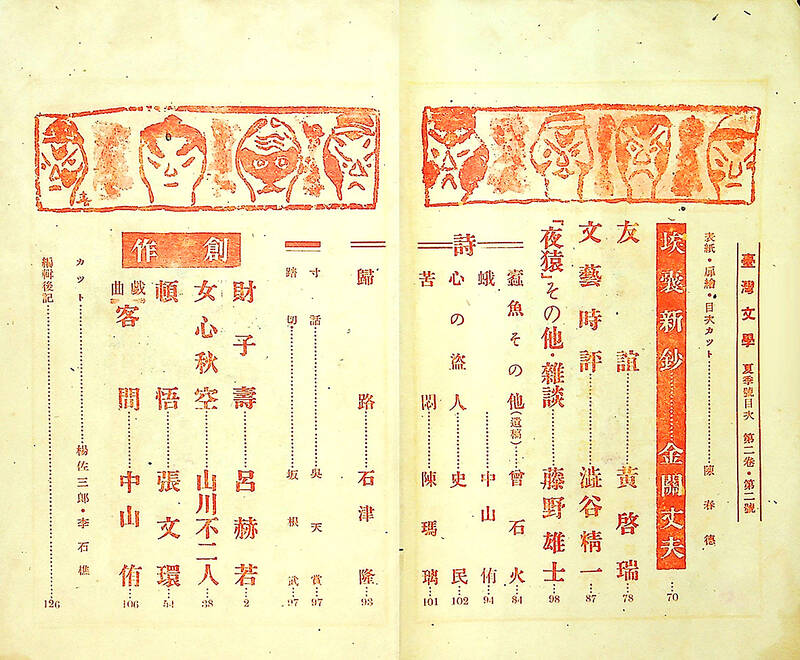

In 1939, Lu went to Japan to study music, during which time he also participated in the acclaimed Takarazuka Theatre Company. He continued his varied interests after returning home, becoming a newspaper reporter and working at the Taiwan Bungaku literary magazine while promoting the colony’s theater scene. He also taught music at Taihoku First Girls’ High School.

Taiwan Bungaku published his second and third novellas, Wealth, Offspring and Longevity (財子壽) and Fengshui (風水), both of which won literary awards. The former examined greed and feudal mentality in a traditional family, while the latter dealt with the collapse of rural morals through two brothers fighting over whether to “pick the bones” of their dead parents. Also known as a “second burial,” the ritual enables the spirits of the deceased to rest in peace and is seen as an act of filial piety.

LIFELONG DISSIDENT

Even though some Japanese critics praised his work, others, such as Mitsuru Nishikawa, attacked Lu and other Taiwanese writers for focusing on the negatives in society and ignoring the “pertinent issues” of the war: imperialism and patriotism.

Faced with such pressure, in June 1943 he wrote in his diary: “Is it finally time to write something that contributes to nationalism? I’ve been writing about the dark side up until now — sure, let’s write about something beautiful!”

The resulting piece, Pomegranate (石榴), had a positive message, but it still focused on the drama in a traditional Taiwanese family.

Clear Autumn dealt with the war. It depicted two brothers who studied medicine in Japan who were faced with the choice of returning to their hometown and becoming respected doctors, or escaping family pressure and heading to serve on the frontlines in the south Pacific — choices framed as a dilemma rather than an effort to glorify the war.

After the war, he wrote several stories about the effects of colonialism on Taiwanese, and continued his journalistic career at the People’s News Leader (人民導報). The paper was critical of the government, and founder Song Fei-ju (宋斐如) was one of the many who were disappeared in the aftermath of the 228 Incident.

By 1949, Lu had committed fully to communism. His fate after fleeing into the mountains was finally confirmed in 2020, when Academia Historica released a document from his comrades in the Luku (鹿窟) communist base that detailed his eight-day struggle after being bitten by the snake in August 1950.

His wife and children were often harassed by the authorities over the decades, and they rarely talked about him until the government began loosening its iron grip on society in the 1980s.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and