Feb. 20 to Feb. 26

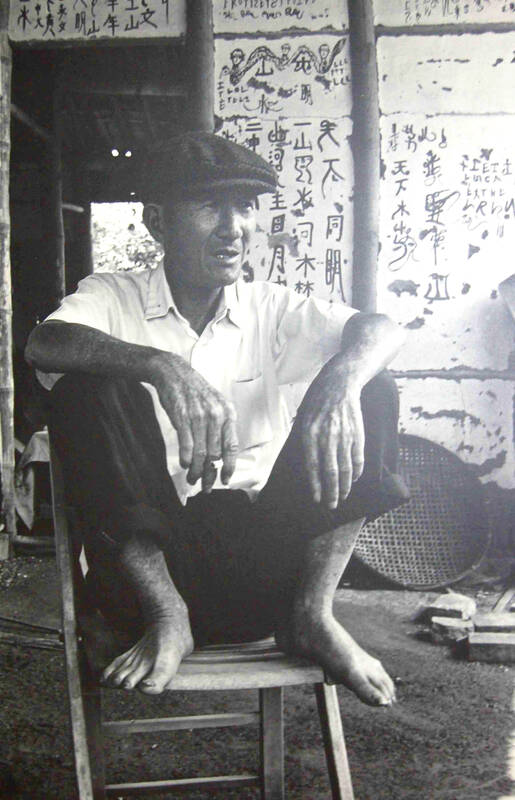

Just a few years removed from the peak of his fame, Hung Tung (洪通) lived alone in a dilapidated house in rural Tainan in the 1980s, working on his art and subsisting mostly on sweet soymilk. His family had moved to Tainan City, but he refused to join them.

Neighbors were mostly used to this peculiar old man, who seemed to live in his own world and rarely interacted with others. Even though he barely had enough to eat, he still refused to sell his paintings. Several months after the death of his wife, Hung passed away on Feb. 23, 1987.

Photo courtesy of Hung Shih-pao

At his posthumous retrospective, his paintings sold for as little as NT$30,000 — quite meager for an artist who was once the talk of the nation. Art collector Chou Yu (周渝) urged Hung’s son to stop selling the paintings, telling him that they would fetch much higher prices in the future.

Chou was right. A second “Hung Tung craze” swept the art world in the 1990s, with one piece fetching NT$3.6 million in 1996. On the ninth anniversary of his death, Hung’s paintings were exhibited overseas for the first time -- first in New York City, then at the Asian Arts & Cultural Center at Towson University in Maryland.

Ever averse to publicity, Hung probably wouldn’t have liked it if he were alive.

Photo: Hsi Yen-hsia, Taipei Times

MIDLIFE CRISIS?

Nicknamed the “Amateur Painter” and “Mad Artist,” Hung was born in 1920 in Kunchiang Village (鯤江) in rural Tainan. It was a barren area, and the illiterate Hung scraped out a living as a fisherman, bricklayer, fishmonger, candle vendor, construction worker and spirit medium.

Soon after he turned 50, Hung’s wife suddenly found him kneeling in front of her, begging her to let him stop working and focus on painting. She declined twice, but finally relented. He clearly remembers that day: it was Nov. 4, 1969.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“My life has been filled with more hardships than happiness,” Hung tells writer Chang Yin (常茵) in an interview. “After I turned 50, I started to experience suffocating feelings of despondence that made me feel sad and mournful. I needed to get that feeling off my chest, so I picked up a stone and started drawing on the ground and the walls. I was engrossed and soon got the hang of it.”

“Drawing was the only way for me to forget the poverty and suffering of everyday life. It made me happy on a spiritual level,” he adds.

Hung locked himself in his room, painting day and night. The villagers looked down on his behavior, convinced that he had gone nuts. His cousins called him a “useless person” to his face, while others said that he was possessed by an evil spirit.

When he did venture out, it was often to see exhibits and to learn from professional artists. Tseng Pei-yao’s (曾培堯) recalls in a Lion Art Monthly (雄獅美術) article seeing a depressed-looking old man from the countryside at his doorstep one day. He had a large roll of drawings that he claimed were made by his farmer friend, and wanted Tseng’s opinion on them.

“When I told him my thoughts, he seemed happy, and said that I was the first person to praise these works. He said others told him they were worthless and worse than a child’s scribblings,” Tseng writes.

Hung insisted that Tseng become his teacher. Between 1971 and 1973, Tseng gave Hung suggestions on material and subject matter, but claims to not have influenced his style.

DISCOVERY OF A MADMAN

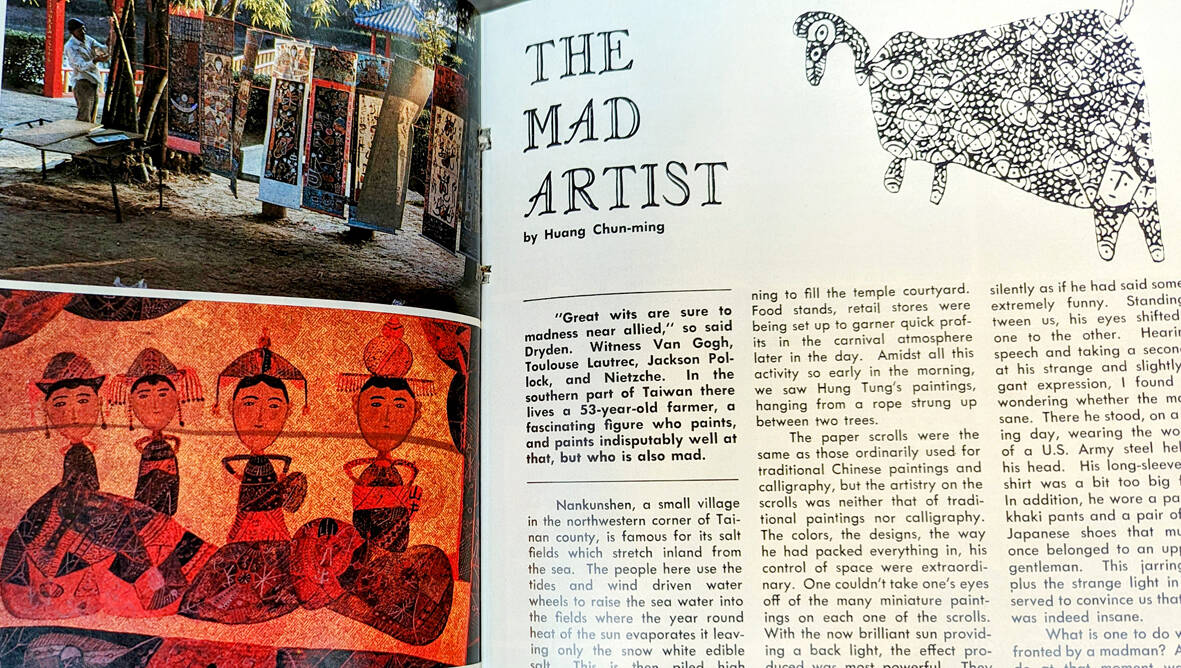

In May 1972, the Wangye temple in nearby Nankunshen (南鯤鯓) held a photography contest. Hung put up about 20 of his pieces near the temple, which caught the attention of an Echo of Things Chinese (漢聲) magazine team who was there to cover the deity’s birthday ceremony.

The English-language magazine published “The Mad Artist” in its July-August edition, describing Hung as a “fascinating figure who paints, and paints indisputably well at that, but who is also mad.”

“The colors, the designs, the way he had packed everything in, his control of space were extraordinary,” author Huang Chun-ming (黃春明) writes. “One couldn’t take one’s eyes off the miniature paintings on each one of the scrolls ... Small figures seemed to be winking at me, beckoning me to come closer, the flowers and shrubs even seemed to exude a sweet fragrance …”

Huang then spoke to Hung, who seemed surprised that they liked the art. Switching between “shy, humble” and “arrogant, self-satisfied” personas, the writer was convinced that Hung was a crazy genius. He found it hard to believe that Huang had never lived outside the village and had only been painting for three years.

The interview ended with Hung accusing them of stealing his paintings and threatening them with martial arts and black magic. They offered to buy some of the work, but Hung refused to sell.

News of the Mad Artist spread, leading to the craze known as the Hung Tung Phenomenon (洪通現象).

The frenzy reached a climax in 1976, when Hung had his first solo show at the US Information Agency office in Taipei. China Times (中國時報) devoted two-thirds of a page to him for six days in a row, leading other media to follow suit. Tens of thousands of visitors packed the venue for the entire two weeks of the exhibition.

However, Hung remained adamant on not selling his paintings and remained destitute. After three exhibitions in one year, he grew tired of the attention and returned home, becoming a recluse.

‘HUNG TUNG PHENOMENON’

Chen Chi-hsiung (陳吉雄) examines Hung’s meteoric rise and fall in Study on the Hung Tung Phenomenon (洪通現象之研究).

According to Chen, Hung’s rise coincided with the “nativist movement” (鄉土運動) in Taiwan, which began in the late 1960s as a pushback against the Western, modernist style that dominated the cultural scene. This sentiment for local culture and identity only grew in the 1970s as the nation suffered setback after setback in the international arena.

“These events sparked a strong sense of crisis and self-awareness among Taiwanese society and the cultural community as they pondered Taiwan’s fate,” Chen writes.

This period saw the rise of Taiwan-born realist writers, as well as ventures by Western-educated musicians to rural areas to “discover” traditional folk music. The fine arts world, however, was still lacking in nativist content by the early 1970s, and Hung’s humble background and reputation as an untrained genius was the perfect embodiment of the sentiment.

“His success was a product of the times,” Chen writes. “Due to the [media frenzy], viewing his art became a trendy thing to do for the masses … as popular culture is often disposable and ephemeral, it’s not hard to understand why Hung Tung’s stardom rose as quickly as it fell.”

Chen adds that most people saw Hung as some sort of fairy-tale figure with a fascinating backstory instead of purely as an artist. They visited his exhibit out of curiosity as if it were a spectacle, and as such, his art was quickly forgotten until it was “rediscovered” a decade later.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful