The Hundred Acre Wood has seen some pretty unsettling things over the years. A honey jar shortage. Rather blustery days. The omnipresent threat of a Heffalump.

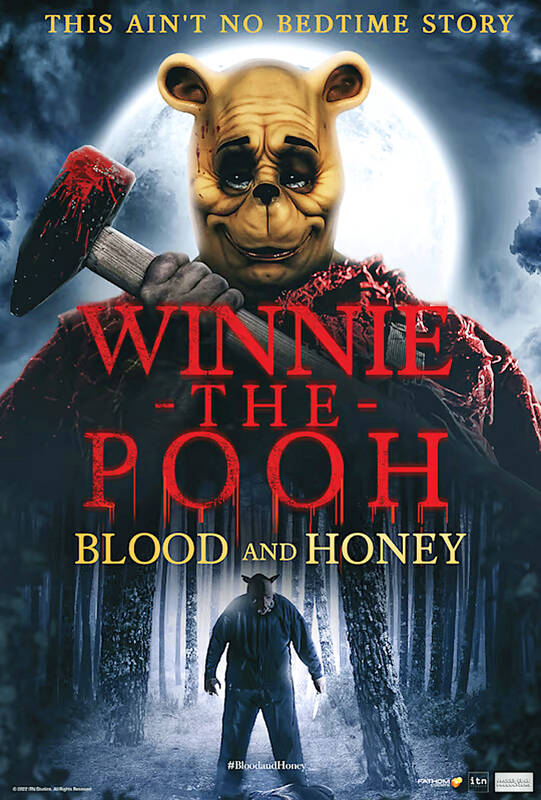

But in Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey, a new microbudget R-rated horror film, Pooh wades into far darker territory than even Eeyore could have ever imagined. After 95 years of saying things like “A hug is always the right size,” Pooh — newly freed from copyright — is now violently terrorizing a remote house of young women.

Countless cherished characters have passed into public domain before, but perhaps never so abruptly and savagely as Pooh.

Photo: AP

Pooh, Piglet, Kanga, Roo, Owl, Eeyore and Christopher Robin all became public domain on Jan. 1 last year when the copyright on A.A. Milne’s 1926 book, Winnie-the-Pooh, with illustrations by E.H. Shepard, expired. Just a year later, Pooh and Piglet can now be found on a murderous rampage in nationwide movie theaters — a head-spinning development that’s happened faster than a bear could say “Oh, bother.”

Depending on how you look at it, Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey is either a crass way to capitalize on a beloved bear or an ingenious bit of independent filmmaking foresight. Either way, it’s probably a harbinger of what’s to come.

In the next 10 years, some of the most iconic characters in pop culture — including Bugs Bunny, Batman and Superman — will pass into public domain, or at least their most early incarnations. Some elements of Pooh are still off-limits, like his red shirt, since they apply to later interpretations. Tigger, who debuted in 1928’s The House at Pooh Corner, isn’t public until next year.

Photo: AP

Many have next Jan. 1 circled. That’s when the original version of Mickey Mouse, from Steamboat Willie, becomes public domain. It will be open on season on the face of the Walt Disney Co — or at least that early whistling variety of Mickey.

Pop culture, as a concept, was born in the 1920s, meaning many of the most indelible — and still very culturally present — works will fall into public domain in the coming years. There will be all kinds of new and unlikely contexts for some of these characters. Some could be wonderful, some schlocky. But Winnie Pooh: Blood and Honey may just be a taste of what’s in store.

“When Superman and Batman fall into the public domain, there’s going to be some wild films, I’m sure of it,” says Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey writer, director and co-producer Rhys Waterfield. “There’s going to be so many different and cool unique iterations coming off that. I might do one.”

Though made for less than US$100,000, Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey will open Friday on some 1,500 screens in North America, an unusually wide release for such a little-funded movie. It’s already made US$1 million in Mexico and has many more international territories booked. For Waterfield, a British film producer of direct-to-DVD titles (credits include Dinosaur Hotel and Easter Killing), it’s already a hit way beyond expectation.

The movie will see its Taiwan release on March 3.

“I kind of thought this could do a small theatrical run in some places and do quite well commercially,” says Waterfield. “But it’s blown up way beyond that to a scale that’s absolutely insane.”

In a 2021 tally of media franchises by Statista, Winnie the Pooh, with US$80.3 billion in worldwide revenue, tied Mickey Mouse for No. 3, trailing only Pokemon and Hello Kitty. But unlike them, Pooh accounts for a veritable religion for his kind-hearted witticisms and contented spiritual outlook. Pooh is as much a gentle sage as he is a round-tummied toon. When Waterfield realized Pooh was entering public domain, “I had a spark in my eye,” he says.

Here was much-coveted intellectual property that could sell just about any film. “I’ve never met anyone that doesn’t know who Winnie the Pooh is,” Waterfield said in a recent phone interview speaking from Amsterdam.

But certainly, not everyone has been so happy about the idea of one of the most benevolent bears turning feral monster. Waterfield says he receives daily messages telling him he’s evil, and even some death threats. One person said they were calling the police.

“You’ve got to be pretty thick-skinned to do a movie like this,” Waterfield says. “It baffles me. People think making an alternative version of him is somehow infiltrating their mind and destroying their memories. When I get claims that I ruined people’s childhoods, I’m genuinely confused. I just kind of brush it off and carry on making more of them.”

Waterfield is already planning sequels with Peter Pan, Bambi and many more. (The Felix Salten book Bambi, A Life in the Woods also became public domain last year.)

Jennifer Jenkins, a professor of law and director of Duke’s Center for the Study of Public Domain, is used to operating in a relatively quiet and byzantine realm of copyright law and thorny rights issues. She writes an annual Jan. 1 column for “Public Domain Day.” But nothing has caused her phone to ring off the hook quite like Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey.

The movie has clearly touched a nerve; millions have watched its trailer online. (Typical comment: “I can’t believe that this movie is real.”) And Jenkins, a firm believer in the long-range benefits of public domain, has been somewhat bemused by the storm kicked up by a movie like Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey. She compares public domain issues like these to the way free speech is a right, regardless of whether you agree with what’s said.

“Some uses of public domain material will be welcome to some and disturbing to others,” Jenkins says. “But I don’t think new content uniformly saps the value of the original work. I have the original books. I adore them. The fact that this slasher film is out there has no effect whatsoever on how I feel about A.A. Milne’s original creation or E.H. Shepard’s pencil sketches.”

It’s worth noting that much of the Disney empire was, itself, built on public domain. Beauty and the Beast comes from Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s 1756 version of the fairy tale. Sleeping Beauty came from Charles Perrault’s 1697 fairy tale. Aladdin comes from the folk tale collection The Book of One Thousand and One Nights.

Though Jenkins can’t think of too many characters who had such a jarring entry to public domain as Pooh, films like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2016) and the 2021 book The Great Gatsby Undead are reference points.

“People love adding zombies to public domain works,” says Jenkins.

To her, Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey may not be the most glorious example of the effects of public domain, but it’s part of a process that human creativity depends upon and thrives on. Blood and Honey may not make a lasting mark in the Hundred Acre Woods, but something, someday will. Chalk it up to growing pains.

“The fact that some people may be disturbed or revolted by this particular re-use of some of the characters from Winnie the Pooh doesn’t detract from the value of the public domain,” says Jenkins. “This is how people throughout history have created. They’ve always drawn on or been inspired by earlier works. Time will tell with this movie or any other reuse of Winnie the Pooh and Piglet whether movies like this will be rewarded in the marketplace or have any enduring appeal.

“My thing is always: Time will tell.”

Cheng Ching-hsiang (鄭青祥) turned a small triangle of concrete jammed between two old shops into a cool little bar called 9dimension. In front of the shop, a steampunk-like structure was welded by himself to serve as a booth where he prepares cocktails. “Yancheng used to be just old people,” he says, “but now young people are coming and creating the New Yancheng.” Around the corner, Yu Hsiu-jao (饒毓琇), opened Tiny Cafe. True to its name, it is the size of a cupboard and serves cold-brewed coffee. “Small shops are so special and have personality,” she says, “people come to Yancheng to find such treasures.” She

The low voter turnout for the referendum on Aug. 23 shows that many Taiwanese are apathetic about nuclear energy, but there are long-term energy stakes involved that the public needs to grasp Taiwan faces an energy trilemma: soaring AI-driven demand, pressure to cut carbon and reliance on fragile fuel imports. But the nuclear referendum on Aug. 23 showed how little this registered with voters, many of whom neither see the long game nor grasp the stakes. Volunteer referendum worker Vivian Chen (陳薇安) put it bluntly: “I’ve seen many people asking what they’re voting for when they arrive to vote. They cast their vote without even doing any research.” Imagine Taiwanese voters invited to a poker table. The bet looked simple — yes or no — yet most never showed. More than two-thirds of those

In July of 1995, a group of local DJs began posting an event flyer around Taipei. It was cheaply photocopied and nearly all in English, with a hand-drawn map on the back and, on the front, a big red hand print alongside one prominent line of text, “Finally… THE PARTY.” The map led to a remote floodplain in Taipei County (now New Taipei City) just across the Tamsui River from Taipei. The organizers got permission from no one. They just drove up in a blue Taiwanese pickup truck, set up a generator, two speakers, two turntables and a mixer. They

Former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chairwoman Hung Hsiu-chu’s (洪秀柱) attendance at the Chinese Communist Party’s (CPP) “Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War” parade in Beijing is infuriating, embarrassing and insulting to nearly everyone in Taiwan, and Taiwan’s friends and allies. She is also ripping off bandages and pouring salt into old wounds. In the process she managed to tie both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) into uncomfortable knots. The KMT continues to honor their heroic fighters, who defended China against the invading Japanese Empire, which inflicted unimaginable horrors on the