Taiwanese collectors are rumored to shun contemporary works on paper, deemed too fragile to withstand the island’s notorious tropical humidity and the voracious pests that go with it.

Somehow, this does not seem to bother Liang Zhaoxi (梁兆熙) who, to this day, only draws and paints on paper sheets, larger formats being then glued onto canvas.

Who is this rare artist? Reading the poster at the entrance of the museum was my first encounter with this China-style pinyin Romanization: I have known him since the end of the nineties as Leung Hsiu-hay (some galleries prefer to spell his name Leung Siu Hee).

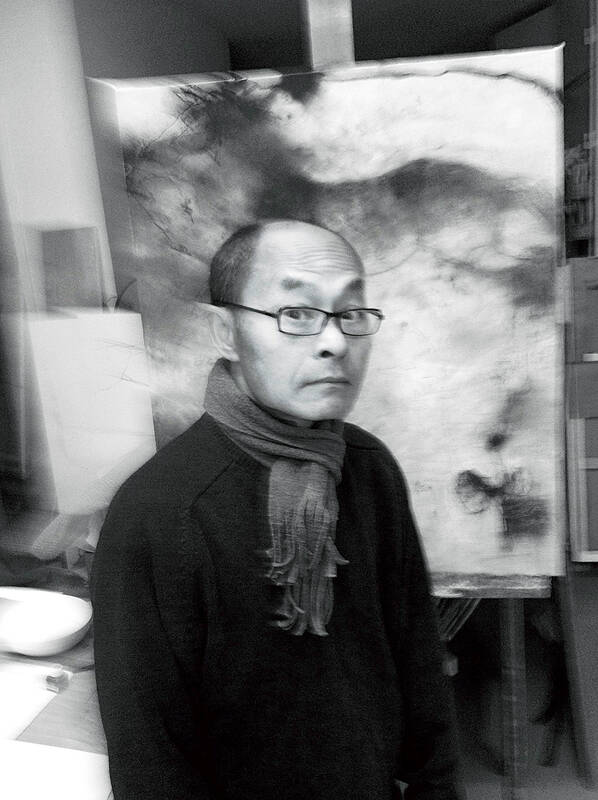

Photo courtesy of Yu-Hsiu Museum of Art

Not at all worried about the added blur to his identity, Liang doesn’t care much how galleries or museums transcribe his name, or what anybody says about him.

“I’d rather my drawings talk for me, lest I influence the viewer,” he told me over the phone in late January. “Really, feel free to write whatever you want, I never read reviews anyway.”

Born in 1953 in the then British-ruled Solomon Islands (and not “Luomen, China”, as I read on the Web with amusement) to parents from Hong Kong, Liang graduated from Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1980.

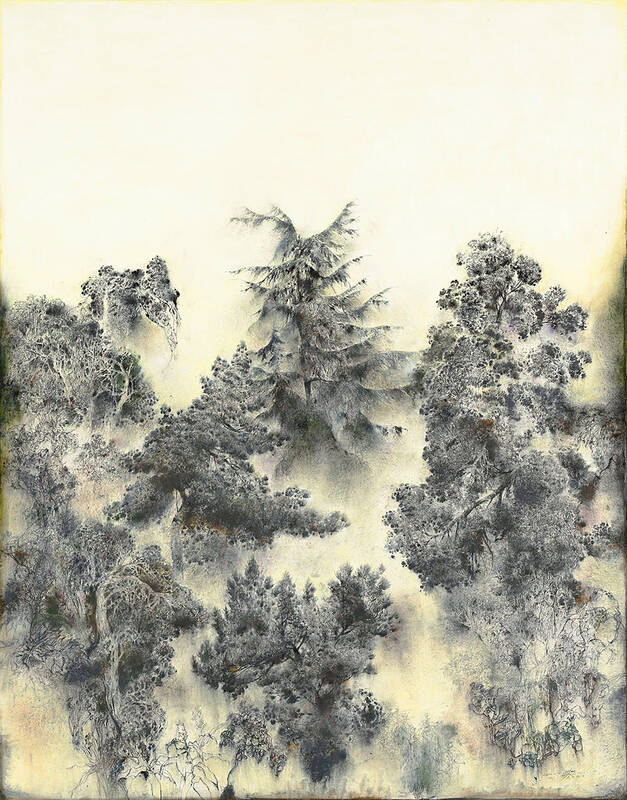

Photo courtesy of Yu-Hsiu Museum of Art

Although he has lived in Paris for over 40 years, Taiwan is the place where he has been exhibiting exclusively since 1990, and he therefore considers himself as an integral member of the Taiwanese art scene.

PETRIFIED CORNUCOPIA

Yet I definitely detect the true Parisian in his habit of loitering in the flea markets of the French capital. This is where, I imagine, he must have encountered this full medieval armor, that beautiful conch shell, that rumpled garment or other sometimes barely recognizable objects, but my guess is that the hippocampus appearing in some of his still lifes is a reminiscence of Hong Kong traditional Chinese medicine counters.

Photo courtesy of Yu-Hsiu Museum of Art

Liang’s unique style revolved in his early works around his use of charcoal, sometimes projected onto the paper in the form of powder by plucking a straightened metal string, which allowed for straight lines that give his works a kind of photographic preciseness.

If Liang may have honed his strong fusain drawing skills at Beaux-Arts, this particular technique comes from a job at a carpenter’s workshop during his student years.

The “black” still lifes of the 80s and 90s feel like a visit to a dusty attic, only guided by the dim light of a lone electric bulb or the rays of the moon shining through disjointed wooden planks.

Photo courtesy of Yu-Hsiu Museum of Art

Another technique employed by Liang is closer to free hand sketching and allows better for the depiction of movement — human silhouettes with gaunt torsos, muscular horses, are caught in the midst of a turn, of a leap.

Liang’s running horses have as much evocative power as those of Paleolithic parietal works such as those seen in Lascaux, in Southern France, and the painter’s hand prints left here and there on some drawings could be another wink to some of the earliest artists in mankind’s history.

Animals, in Liang’s drawings, are royal and serious, yet you might also sense in their straight gaze a hint of mischievousness or simple confidence.

If I am allowed by Liang himself to give you my personal interpretation, then this is the artist at work, taking the silly world around him with a pinch of salt.

TWO WORLDS

I invite you to savor the view of his tranquil hares which take us back to Albrecht Durer and other Renaissance masters.

The hare, or the rabbit, has been a recurrent motive in Western art at least since the Renaissance: See for instance the extraordinary Dame a la Licorne tapestry dated circa 1500, which is hung in the Cluny Museum in Paris.

Liang acknowledges that after 40 years in France, he is indeed “influenced by French culture,” but how could he not have first and foremost an intimate knowledge of the masterpieces of Chinese classical art?

His beautiful furry creatures, among other members of his rich bestiary, could very well be having a conversation with Magpies and Hare (雙喜圖), the painting by the mid-11th Northern Song painter Tsui Pai (崔白) that is one of the highlights of the National Palace Museum (NMP) collections.

It is a delight to see exhibited here one example of Liang’s ominous mountains, where the huge mass of land occupies most of the space.

Again, I like to see here a clear reference to famous classical Chinese ink paintings such as Travelers among Mountains and Streams (谿山行旅) by Fan Kuan (范寬), another Song dynasty painter and NPM favorite.

I personally wished I had seen in this exhibition more of Liang’s earlier “black” works such as Untitled (1983) depicting a table laid with various objects under the cone of a hanging light.

Liang is here a master at his own game of depicting “dark brightness falling from the stars,” to paraphrase 17th century French tragedian Pierre Corneille.

Over the years, somber lights have gradually allowed color pigments to seep through, and carbon black has eventually receded somewhat against light yellow or creme backgrounds.

That is the case for instance with two large works depicting mountain slopes with conifers emerging as if from mellow snow or icy mist.

Lately, plants in Liang’s works seem similarly less desiccated and dusty, less brittle, and since the mid-2010s, roses are indeed in bloom.

Art critics are heard wondering aloud if this might be a sign of the serenity said to come with advancing age — just do not ask the artist to confirm.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on