Feb. 6 to Feb. 12

The plan was to break out of jail, seize the facility’s ammunition, release the inmates and broadcast their “declaration of Taiwanese independence” to the world at the nearby Broadcasting Corporation of China station.

Chiang Ping-hsing (江炳興) and his fellow political prisoners at Taiyuan Prison (泰源監獄) hoped that this action would attract international attention and spark a nationwide rebellion that would overthrow Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) authoritarian regime.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It was originally planned for Feb. 1, 1970, but due to various setbacks they weren’t able to strike until the noontime guard change at the prison on Feb. 8. They attacked the six guards and wrestled away their guns while fatally stabbing one of them, but the commotion had already alerted other guards, making any further action impossible.

Chiang Ping-hsing and his five collaborators fled into Taitung’s mountains of and hid for over a week until they were captured. Although capital punishment was almost certain, they refused to name any other conspirators, which allegedly included over 100 prisoners and locals. They also insisted that Cheng Cheng-cheng (鄭正成), one of the escapees, was forced to come along as a hostage, resulting in him being the only one to escape death.

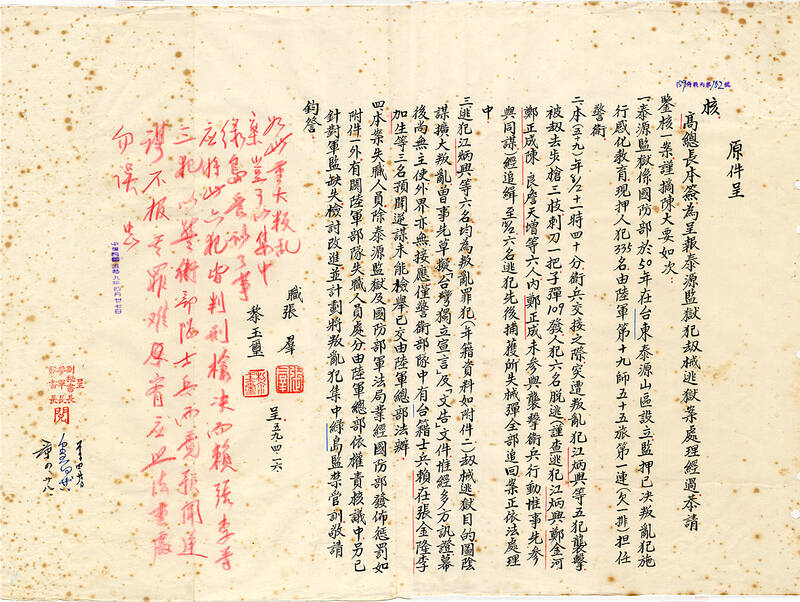

According to a 2018 report by Academia Historica president Chen Yi-shen (陳儀深) for the National Human Rights Museum (NHRM), the only other people arrested were three Taiwanese prison guards who knew about the plot but failed to report it. Several officers also received demerits. The five were executed on May 30, while Cheng received an additional 15 years on top of his existing sentence.

Photo courtesy of National Human Rights Museum

Although botched, it was one of the few armed uprisings during the Martial Law era that actually got off the ground. Dubbed the “Taiyuan Riot” by the government and “Taiyuan Revolution” by activists, historians generally refer to it today as the “Taiyuan Incident.”

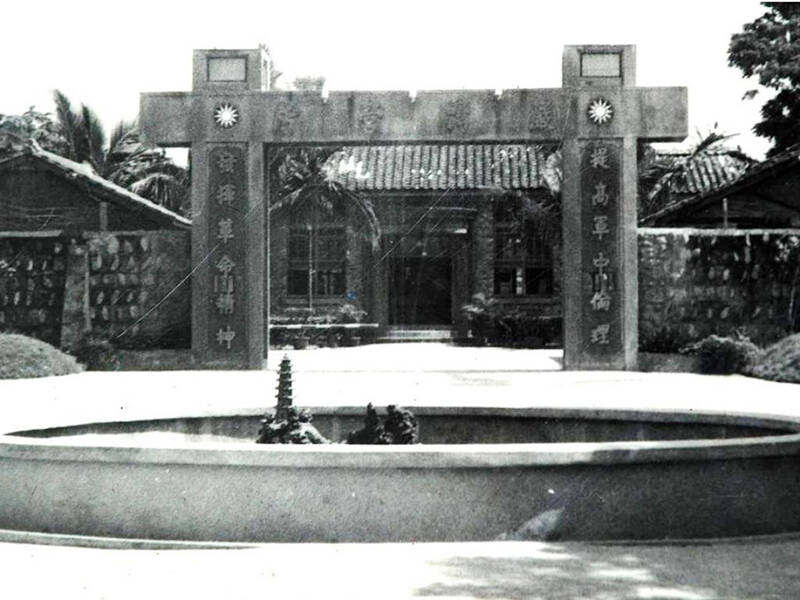

The event led to the rapid construction of the high-security “Oasis Villa” on Green Island, where all prisoners were transferred in 1972.

BOILING POINT

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In March 1960, Chiang Kai-shek extended his presidential term limit indefinitely, leading to much disappointment and discontent among local politicians. An attempt to form an opposition party to challenge him was squashed in September, which, according to Chen Yi-shen, led many to believe that an armed uprising was the only remaining option to restore democracy.

Meanwhile, the political arrests continued. In 1962, the Taiyuan Prison in Taitung County’s Tungho Township (東河鄉) replaced Green Island as the nation’s largest facility for political prisoners. However, Chiang insisted to the outside world that Taiwan did not have political prisoners and that it was just a small group of exiled politicians that were agitating for independence overseas.

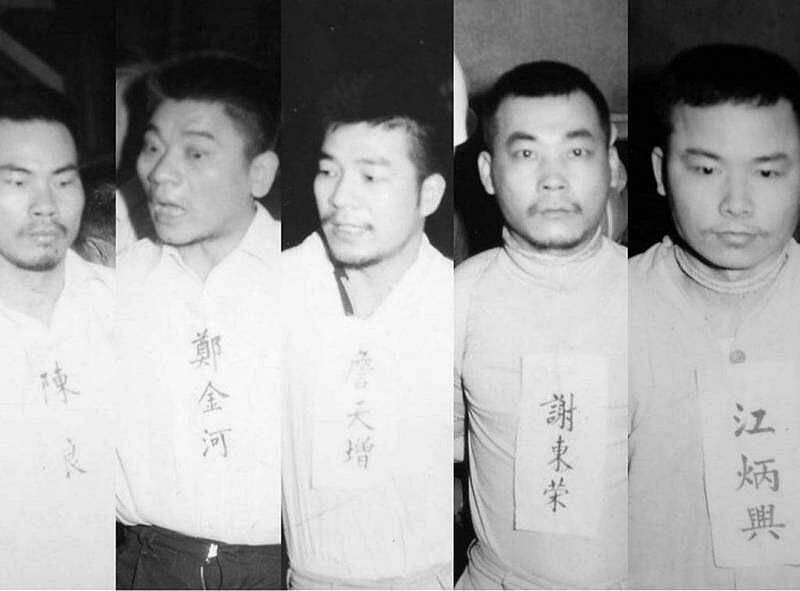

Countless White Terror prisoners were jailed on bogus charges, but five of the six Taiyuan Incident convicts actually took part in pro-independence activities. Cheng Chin-ho (鄭金河), Chen Liang (陳良), Chan Tien-tseng (詹天增) and Cheng Cheng-cheng were among 50 people sentenced in 1961 for the Su Tung-chi (蘇東啟) incident, a planned armed rebellion that was snuffed out before it could begin. Chiang, a 22-year-old army cadet, was arrested the following year for joining a pro-independence group. Hsieh Tung-jung (謝東榮), on the other hand, was given seven years in 1966 just for writing a “revolutionary” message in the bathroom stall of his military school.

Despite having served the bulk of their sentences by 1970, they were determined to give their life for the cause, each penning final letters to their family. Their manifesto states: “Why are Taiwanese only allowed to have one voice? Why can Taiwanese only choose one fate? Why are Taiwanese resigned to obedience, and are not able to rise up and resist authoritarian rule?”

A major motivation to carry out the uprising was to support activist Peng Ming-min’s (彭明敏) attempt to flee the country and let the world know about the government’s political oppression. It was a precarious time as Taiwan’s seat in the UN was being questioned, and the activists felt that it was time to at least make some noise even if the operation failed.

TAKING ACTION

Fellow prisoner Ke Chi-hua (柯旗化) says in the NHRM report that the prisoners who were assigned tasks outside the facility walls established good relationships with the Taiwanese guards as well as the indigenous neighbors, and obtained their support in a potential uprising. Supervision was quite relaxed, and they could converse freely with people they met.

Tsai Kuan-yu (蔡寬裕) says that Cheng Chin-ho was the one who came up with the idea, but things didn’t pick up until the more “radical” Chiang Ping-hsing arrived in 1969. Chiang immediately obtained privileges to work outside due to one of the higher-ranking officers being his former classmate.

“This speeded up the development of the events,” Tsai says. “Chiang also had more military knowledge than the other outside prisoners, so he quickly became the central figure for the event.”

The prisoners allowed outside regularly discussed their plans with those inside, which included Tsai, Kao Chin-lang (高金郎) and Shih Ming-te (施明德). They were to provide support after the guards were subdued, such as releasing other inmates from their cells.

According to the official report, the six prisoners struck during the change of the guard. Facing six armed guards, Chiang yelled, “Taiwan is independent now, give us your guns!” A struggle ensued and the prisoners succeeded in obtaining the weapons. However, guard Lung Run-nian (龍潤年) was stabbed twice and later died.

The other guards rushed to the scene and a standoff ensued. The prisoners eventually escaped through an orchard. Some say a sympathetic guard let them escape. Chiang was the first to be caught five days later, and the rest were nabbed one by one.

AFTERMATH

Chen Yi-shen’s report shows that the six refused to mention any names over the weeks of intense torture and interrogation. Many believe that this ensured Cheng Cheng-cheng’s survival so he could tell the truth to the future generations.

But Cheng’s story is confusing. He says in an Academia Sinica oral history interview in 2002 that he was involved throughout the action, but in a 2017 interview he claims that he wasn’t present when the struggle broke out; he’d simply ran toward the hills after hearing the commotion and met up with his comrades later.

The official verdict is even more confusing. It first describes Cheng as being on scene during the attack, but later states that he refused to partake at the last minute. They decided that if they also executed Cheng, “the Taiwanese independence conspirators would surely use it as propaganda and affect the minds of our Taiwanese compatriots.”

Before Cheng Chin-ho’s execution, he told Cheng Cheng-cheng: “If Taiwan doesn’t become independent, that would be the shame of our generation. I’m going now, the rest is up to you all.”

Although the remaining collaborators escaped punishment, several had their releases delayed for no apparent reason after finishing their sentences on Green Island.

In October 2021, the five executed were acquitted of sedition after the Transitional Justice Committee deemed that they did not receive a fair trial.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)