Jan. 16 to Jan. 22

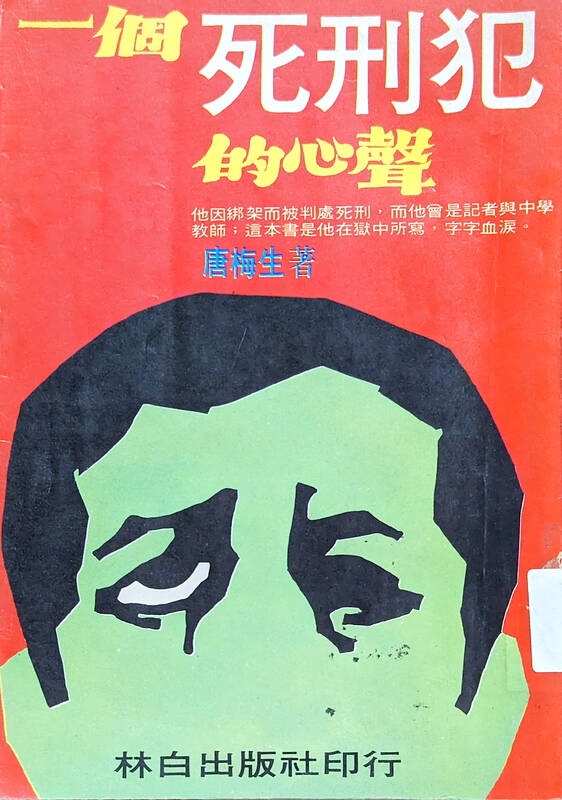

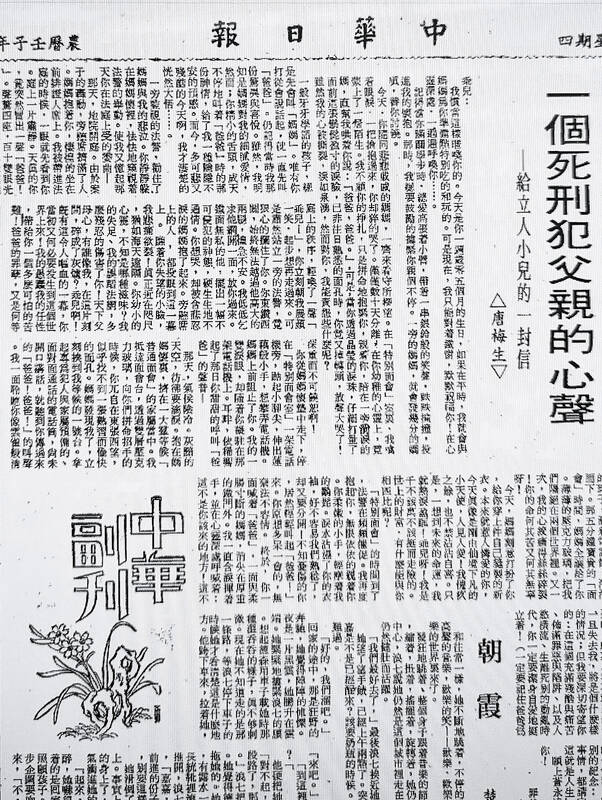

Titled “Confessions of a Father on Death Row,” (一個死刑犯父親的心聲), Tang Chen-huan’s (唐震寰) literary debut was one of sorrow and regret.

It ran in the literary supplement of the China Daily News (中華日報) on Jan. 18, 1972, and marked the beginning of Tang’s literary career, which included several awards and a movie adaptation. He was the nation’s first inmate to pay taxes on book royalties.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The well-liked former junior high school teacher was condemned for kidnapping the children of a businessman who had cheated him out of a large sum of money. Although he returned the kids unharmed, such crimes were punishable by death during the Martial Law era.

“I wrote for nearly 20 hours a day, because I didn’t know if I would be dragged out and executed when the morning came,” he writes in a Xiangguang Magazine (香光莊嚴) article in 1996. “As long as I could still breathe, I wanted to write down all the words I wanted to say … I hoped that those in precarious situations, or those who sought revenge, could see me as an example and refrain from doing something they would regret forever.”

Tang’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 1975, and he was transferred to the Taichung Prison. By 1980, he had written 156 essays, short stories and novels, according to a Taiwan Panorama (台灣光華) article.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

When the organizers of the 1979 National Army Literature and Arts Award learned that their bronze medal winner was an inmate, they traveled to the prison and held for him a formal ceremony, a move that garnered much public attention. He won the award four more times.

Tang was paroled in May 1985 after serving 12 years and eight months. At the press conference, he again told the public not to do what he did, and performed the hit song Last Night’s Stars (昨夜星辰) before walking out the gates a free man.

WRONG STEP

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Born in Hunan Province, China, Tang joined the Republic of China Air Force at a young age, and was about 17 years old when he arrived in Taiwan with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in 1945. He began teaching junior high physics and chemistry in 1956, and ran a lab equipment shop with his wife.

“I was beloved by my students and trusted by my colleagues, and I enjoyed a very happy marriage. I also earned good money,” he writes. “But before I noticed, I had become arrogant. I got carried away, and my self discipline started to wane.”

Tang somehow decided that the kidnapping was the most clever way to handle his predicament, as he did not think direct confrontation or violence would work. He recalls in the 1996 article that if he had actually beaten up the businessman, he would have been charged with assault, which did not carry a death sentence.

“Looking back, It was my destiny for this to happen,” he writes. “Otherwise I wouldn’t be able to share my story with my readers.”

But Tang was furious. He recalls screaming at the judge, “I’m the victim here, you’re putting me on trial while those who swindled me remain at large. Does the law only protect bad people?”

While appealing his death sentence, Tang wanted to do something to calm his mind. The prison wouldn’t allow science experiments, so he picked up a pen and began writing. His first piece described the remorse he felt toward his one-year-old son, and the torment he felt during every visit. He was left in tears when his son called out to him in the courtroom, or innocently played with his handcuffs.

“In this cruel and painful world full of sin and pitfalls, unbridled indulgence and separation between loved ones, you must respect yourself and stand tall. You must remember the lesson of your father being punished for his greed.”

PUBLIC ENCOURAGEMENT

Tang’s moving letter to his son received an outpouring of sympathy from readers, many of whom wondered what landed him in prison. After publishing a letter to his wife, he decided to reveal in the next essay what exactly happened.

Tang didn’t initially know who cheated him, but six months later he found out who was behind the plot. He began scheming ways to exact revenge. On Oct. 26, 1971, he had a female accomplice pretended to be an elementary school teacher, and the ruse enabled them to kidnap the children.

When Tang reached the negotiation spot, he noticed that it was swarming with scary-looking men. Realizing that the thief was probably a gangster, he gave up and released the children. The next day, he was arrested.

While in jail, he picked up a book by then-premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), who wrote: “There are only two people in the world who can enjoy true happiness: those who forever do good and never commit any crimes, and those who have sinned but are able to repent and reform themselves.”

LATER WRITINGS

Tang’s works soon went from autobiographical to creative fiction, most of them containing strong moral messages. His first award-winning story, Bridge (橋), depicted how two rival villages on opposite sides of a river that were able to forgive generations of hatred. His 1985 book, I Kidnapped My Student (我綁架了我的學生), was made into a movie.

There’s not much information about what happened to Tang after his parole. He seemed to have undergone some sort of spiritual awakening in the 1990s, writing a series of self-help books , while avoiding religious scams.

His final book, cataloged by the National Central Library, was published in 1997, by which time he would have been about 70. There’s a section on how to live to 200 years old.

In the introduction, he writes: “If you’re troubled by love, suffering from family conflict, upset due to poor interpersonal relations, desperate due to financial struggles and you’re about to fall apart, before you seek to end your life, call this number. I will turn your life around for free, and open for you a new outlook.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the