For thousands of years, predictions of apocalypse have come and gone. But with dangers rising from nuclear war and climate change, does the planet need to at least begin contemplating the worst?

When the world rang in 2022, few would have expected the year to feature the US president speaking of the risk of doomsday, following Russia’s threats to go nuclear in its invasion of Ukraine.

“We have not faced the prospect of Armageddon since Kennedy and the Cuban missile crisis” in 1962, Joe Biden said in October.

Photo: EPA-EFE

And on the year that humanity welcomed its eighth billion member, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned that the planet was on a “highway to climate hell.”

In extremes widely attributed to climate change, floods submerged one-third of Pakistan, China sweat under an unprecedented 70-day heatwave, and crops failed in the Horn of Africa — all while the world lagged behind on the UN-blessed goal of checking warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

BIGGEST RISK YET OF NUCLEAR WAR?

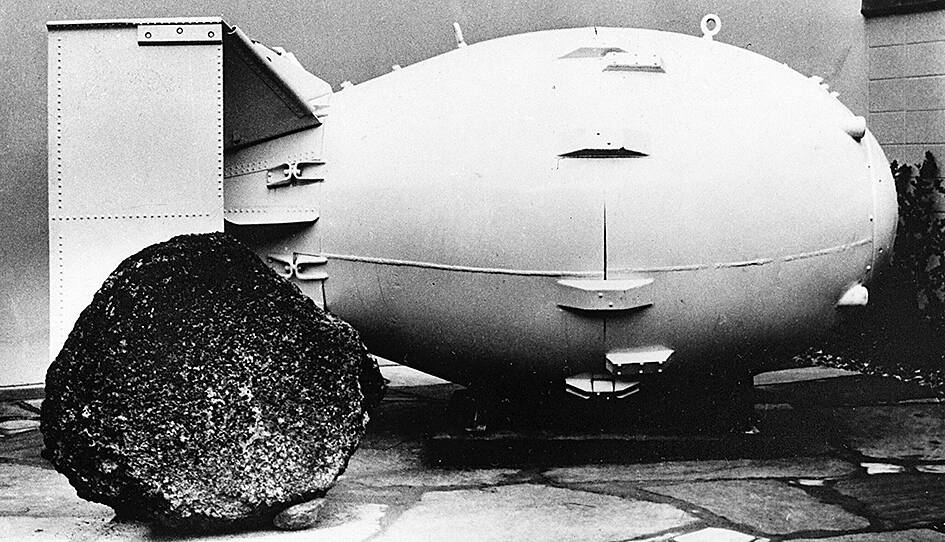

Photo: AP

The Global Challenges Foundation, a Swedish group that assesses catastrophic risks, warned in an annual report that the threat of nuclear weapons use was the greatest since 1945 when the US destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in history’s only atomic attacks.

The report warned that an all-out exchange of nuclear weapons, besides causing an enormous loss of life, would trigger clouds of dust that would obscure the sun, reducing the capacity to grow food and ushering in “a period of chaos and violence, during which most of the surviving world population would die from hunger.”

Kennette Benedict, a lecturer at the University of Chicago who led the report’s nuclear section, said risks were even greater than during the Cuban Missile Crisis as Russian President Vladimir Putin appeared less restrained by advisers.

While any Russian nuclear strike would likely involve small “tactical” weapons, experts fear a quick escalation if the US responds.

“Then we’re in a completely different ballgame,” said Benedict, a senior adviser to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which in January will unveil its latest assessment of the “doomsday clock” set since last year at 100 seconds to midnight.

Amid the focus on Ukraine, US intelligence believes North Korea is ready for a seventh nuclear test, Biden has effectively declared dead a deal on Iran’s contested nuclear work and tensions between India and Pakistan have remained at a low boil.

Benedict also faulted the Biden administration’s nuclear posture review which reserved the right for the US to use nuclear weapons in “extreme circumstances.”

“I think there’s been a kind of steady erosion of the ability to manage nuclear weapons,” she said.

CHARTING WORST-CASE CLIMATE RISKS

UN experts estimated ahead of talks in Egypt last month that the world was on track to warming of 2.1 to 2.9 degrees Celsius — but some outside analysts put the figure well higher, with greenhouse gas emissions in 2021 again hitting a record despite pushes to renewable energy.

Luke Kemp, a Cambridge University expert on existential risks, said the possibility of higher warming was drawing insufficient attention, which he blamed on the consensus culture of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and scientists’ fears of being branded alarmist.

“There has been a strong incentive to err on the side of least drama,” he said.

“What we really need are more complex assessments of how risks would cascade around the world.”

Climate change could cause ripple effects on food, with multiple breadbasket regions failing, fueling hunger and eventually political unrest and conflict.

Kemp warned against extrapolating from a single year or event. But a research paper he co-authored noted that even a two-degree temperature rise would put the Earth in territory uncharted since the Ice Age.

Using a medium-high scenario on emissions and population growth, it found that two billion people by 2070 could live in areas with a mean temperature of 29 degrees Celsius, straining water resources — including between India and Pakistan.

CASE FOR OPTIMISM

The year, however, was not all grim. While China ended the year with a surge of COVID-19 deaths, vaccinations helped much of the world turn the page on virus, which the WHO estimated in May contributed to the deaths of 14.9 million people in 2020 and last year.

Surprising jaded observers, a conference this month in Montreal on biodiversity produced a major deal to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and seas, with China leading the way.

The world has seen previous warnings of worst-case scenarios, from Thomas Malthus predicting in the 18th century that food production would not keep up with population growth to the 1968 US bestseller The Population Bomb.

One of the most prominent current-day critics of pessimism is Harvard professor Steven Pinker, who has argued that violence has declined massively in the modern era.

Speaking after the Ukraine invasion, Pinker acknowledged Putin had brought back interstate war. But he said a failed invasion could also reinforce the positive trends.

Biden, in a Christmas address to Americans, acknowledged tough times but pointed to the decline in COVID and healthy employment rates.

“We’re surely making progress. Things are getting better,” Biden said.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,