Dec 5 to Dec 11

Recent visitors to Taipei’s Guangzhou Street Night Market (廣州街) may have noticed that the old concrete building with traditional tiled roofs at No. 200, which spans an entire block, is undergoing renovation.

Jen Chi Hospital (仁濟醫院) maintains that it was just doing “emergency maintenance” when it partially demolished the building’s second floor walls in September, but the city stopped them and declared last week the 71-year-old structure a historic building.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Since it still housed the hospital’s rehabilitation and dentistry departments, the hospital said that the structure was suffering from severe water damage and repairs were needed for the safety of the patients and staff.

The hospital argued that the building was not its original site, and has little historic connection to the people involved in the institution. The Taipei City Government, on the other hand, says that it has been on their culture heritage watch list for years.

According to the hospital’s Web site, they expanded their facilities to this site in 1922. They first built a wooden, one-story structure that served as a 16-bed clinic with an x-ray room and operation center. The marble plaque in front of the building indicates that the current structure was built in 1951, and the city finds historic value in the pebble terrazzo walls and classic window grills typical of hospital designs of that era. Hospital officials, however, say that it lacks any unique technique or design, and is made from ordinary material.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Jen Chi Hospital has been an important landowner during Wanhua [District’s, 萬華] history and it has been closely tied to the area’s development,” the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs states. “This building has played a role in local healthcare for many decades.”

Not much additional information can be found about the building, but the Jen Chi organization actually has an interesting history in Taiwan, starting in 1899 as a government-organized social charity. Today it remains a major landowner in Taipei, with the Liberty Times (Taipei Times sister paper) in a 2017 article calling it the “wealthiest charity in the nation.”

MERGING FORCES

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Jen Chi Relief Institution was launched in May 1899 as a merger of three Qing-era institutions. Wanhua’s Yuyingtang (育嬰堂), which cared for abandoned babies — many of them female — and orphans, was started in 1870 by magistrate Chen Pei-kuei (陳培桂) with the support of the local gentry. It was located on Guangzhou Street, which was once called “Along Yuyingtang Street” (育嬰堂邊街).

This collaboration between government and wealthy locals in social welfare was common across the Qing empire as a way for them to maintain prestige and earn people’s respect. Chen Yen-chen (陳燕禎) writes in the study, “The Changing Relationship between the state and indigenous non-profit organizations” (政府與本土非營利組織關係之轉變), that the institution practiced reactive medicine rather than preventative medicine, and served to appease the people instead of working to alleviate poverty.

Yangjiyuan (養濟院) cared for the poor, sick and elderly who lived alone, and Tongshantang (同善堂) focused on supporting the families of dead soldiers and people who died unexpectedly, whether due to accident or crime.

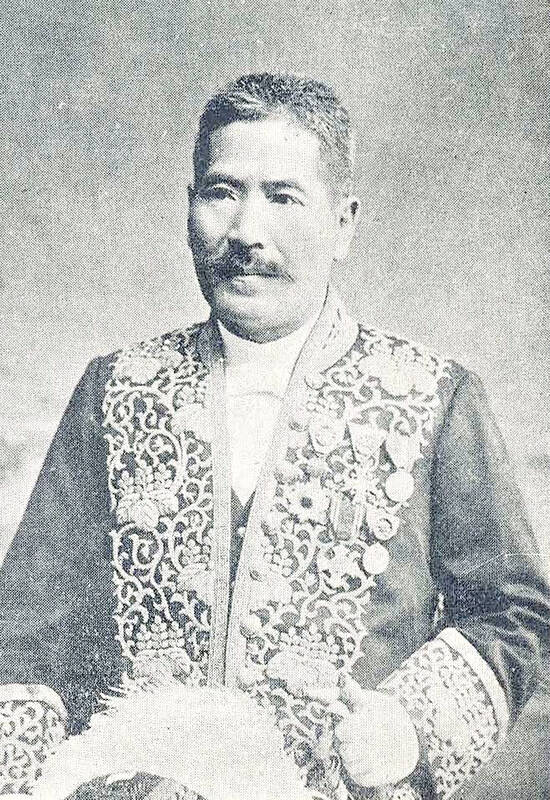

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Many social welfare institutions fell on hard times during the first few years of Japanese rule (1895-1945), some closing down and leaving its residents homeless and begging on the streets. The Japanese colonial government first provided monetary support, but in 1899, with money coming in from empress dowager Eisho’s memorial fund, then-governor-general Gentaro Kodama was able to launch Jen Chi after donating a portion of his salary and holding a local fundraiser. It was run by the Taihoku County Government, which then included today’s Taipei, New Taipei City, Taoyuan, Hsinchu and Yilan.

A fourth institution, Huichunyuan (回春院), which served travelers who fell ill while visiting, was added to the roster in 1904. Two years later, the organization received a major boost in resources by absorbing the orphanage Baoyingju (保嬰局), which was established in 1866 by Lin Wei-yuan (林維源) of the wealthy Banciao Lin family.

Over the years, it added local branches across the colony, including one in Penghu. Its duties were broad, also handling healthcare and foster family placement, and in 1912 it launched a mental health clinic and a school for the deaf and blind in Taipei. It housed 138 residents that year.

The original site fell into disrepair, and in 1922 Jen Chi moved into a new building and expanded its facilities to include several medical clinics divided by specialty, one of them housed in the original wooden building on 200 Guangzhou Street. They also established Taiwan’s first home for the mentally ill. In 1923, Jen Chi became an incorporated foundation and was no longer headed by the local government chief but an appointed director. Funding and operations remained mostly stable for the rest of Japanese rule.

GOING PRIVATE

With World War II and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) unstable new rule, Jen Chi fell onto hard times again. Medical supplies were in short supply, and staff were having trouble collecting rent from Jen Chi properties.

Taipei Prefecture Takeover Committee’s Lien Chen-tung (連震東) tried to take control of Jen Chi for the KMT, but the government didn’t want it because it was already stretched for resources fighting the Chinese Civil War, Chen writes.

With Jen Chi on the verge of collapse, Lien and three others secured private bank loans to keep it afloat. The directors had a lot of influence with the public and government. The first chairman was Taipei mayor Yu Mi-chien (游彌堅), who was able to force renters to pay up, and also kept donations flowing with his connections. Yu served until his death in 1971, upon which Lien took over. His daughter-in-law Lien Fang-yu (連方瑀) now serves on the board.

In 1950, Jen Chi became a private incorporated foundation. This change from public to private has garnered some discussion recently, but that will not be discussed here. Its facilities were given a makeover the following year, including the construction of the current 200 Guangzhou Street structure.

In 1976, the government ordered all charity homes to drop the character “chi” from their names, as it meant “to save” and they said it was harming the dignity of the residents. Due to the board’s power, Chen writes, Jen Chi’s Taipei branch was the only group that requested and received special permission to retain its original name.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any