Winter is the best season — the only season, many would argue — in which long walks near sea level are enjoyable.

Remembering that Miaoli County is often very pleasant in the cool season, with little of the pollution that often plagues Taiwan’s south during that time of year, I broke out a map and scanned parts of the county I’m not familiar with. I hoped to work out a route that’d link a few points of interest I’d not visited before, and also begin and end at places served by public transportation.

Jhunan Township (竹南), which has a population of 87,000, seemed to satisfy my criteria. This township, in the northwestern part of the county and abutting Hsinchu City, is easy to reach by TRA trains. I figured that, by walking for four or five hours, I’d be able to reach half a dozen noteworthy locations.

Photo: Steven Crook

Strolling out of Jhunan TRA Station on a crisp yet sunny morning, I marched due west, not stopping until I’d escaped from the urban core, and reached what looked like it may once have been a small town in its own right.

Cihyou Temple (慈裕宮) is the main landmark in Jhonggang (中港), where some of the houses certainly date from before World War II. Nothing inside suggests antiquity, but the sea goddess Matsu is said to have been worshiped here since 1783.

JHUNAN SEASIDE FOREST RECREATION AREA

Photo: Steven Crook

Between the temple and the Taiwan Strait, the landscape was typical lowland Taiwan, neither urban nor rural. Exactly an hour after leaving the railway station, and a few minutes after walking beneath an elevated section of Freeway 3, I reached what Miaoli County Government’s Web site calls Jhunan Seaside Forest Recreation Area (竹南濱海森林遊憩區), but which other sources label Jhunan Haibin Natural Park (竹南海濱自然公園).

The forest itself isn’t that impressive, but the bike/pedestrian trail through it makes for good walking. Several information boards introduce features of the local ecosystem, including birds, beetles, cicadas, fiddler crabs, frogs and plants.

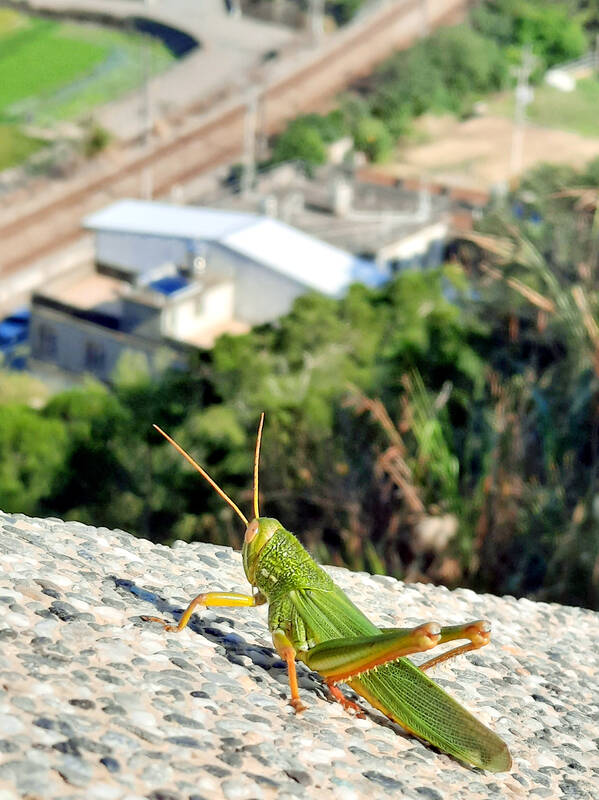

When I moved closer to one board to learn about the area’s population of Chondracris rosea grasshoppers, the scuttling of three creepy crawlies, each as wide as a fingernail, made me jump back.

Photo: Steven Crook

These weren’t grasshoppers, that was obvious. I snapped some photos, and managed to identify them when I got home. They were Amphibious litter cockroaches (Opisthoplatia orientalis).

A sign told me I was 2.3km from Evergreen Forest (長青之森), so I decided to stop ambling and start moving with purpose. Evergreen Forest is apparently a good place for butterfly watching, but instead of searching for lepidopterans, I pressed on a few hundred meters more to Jhunan Wetland (竹南溼地).

This manmade body of water was created at the same time as the edifice that stands to the immediate southeast. I won’t pretend that Miaoli County Refuse Incineration Plant (苗栗縣垃圾焚化廠) is any kind of tourist attraction, but the wetland is an attractive picnic spot.

Photo: Steven Crook

A sign next to the bike trail pointed to my next destination: Wufu Bridge (五福大橋), 4km away. To reach it, I had to veer away from the estuary of the Zhonggang Creek (中港溪), the waterway that separates Jhunan from Houlong (後龍), and take narrow farmers’ roads back toward Freeway 3. There was no tree cover, and it was now well past mid-morning. Luckily, I’d remembered to bring a hat.

GUANYIDU ECO PARK

By the time I reached Guanyidu Eco Park (官義渡生態公園), at the northern end of the bridge, I felt I deserved a proper rest. I’d hiked about 11km, and still had a fair way to go.

Photo: Steven Crook

From the upper level of the park’s two-story pavilion, I could look across a thriving mangrove swamp to Expressway 61 and the wind turbines that lie just offshore. According to an information board, the avian population hereabouts includes Black-winged stilts, Common greenshanks, Black-crowned night herons and Western cattle egrets.

On the south bank of the Jhonggang Creek, I followed Miaoli County Local Road 9 (苗9) inland for 1.5km to Provincial Highway 1. After recaffeinating at a convenience store, I walked south along the highway, not quite sure where I’d find the path to the final attraction on my itinerary.

At the 102.5km marker, I turned off the main road. One minute later, to the left of a dormitory for students attending Yu Da University of Science and Technology (育達科技大學), a hand-painted sign told me I was heading in the right direction for the Zheng Han Memorial (鄭漢紀念碑).

Photo: Steven Crook

ZHENG HAN MEMORIAL

The first part of the ascent was a steep farmer’s road. Soon, I saw a set of broad wooden steps. After these, the trail was paved with stones, then it became a dirt path through woodland.

Reaching the memorial from the main road took me just over 20 minutes — and the 180-degree view was superb, even though it’s just 40m above sea level. Thanks to the clear weather, I could see the rivermouth, central Jhunan and several mid-elevation mountains.

An inscription at the base of the edifice explains why Zheng Han (鄭漢) deserves a memorial.

On Sept. 2, 1965, when he was aged 17 or 18, he jumped into a tributary of the Zhonggang Creek (中港溪) to rescue two drowning children. He saved them, but lost his own life.

To commemorate his bravery and selflessness, the local government cooperated with private-sector donors to establish this 18m-tall memorial. Military personnel stationed nearby lugged bags of cement, sand and gravel up to the construction site.

The memorial melds the image of a man with that of a candle, because, just as a candle burns itself to provide others with light, Zheng sacrificed his own life so others could live.

I spent the better part of an hour at the memorial, taking in the scenery, resting my legs and watching trains approach the historic Japanese-era wooden station building at Tanwen (談文), less than 1km to the east as the crow flies.

By the time I got back down to the trailhead, I’d hiked something like 16km. Rather than walk along a busy road and board a train at Tanwen, I decided I’d finish my tramp right there and catch a bus. I timed it almost perfectly: I hadn’t been at the stop more than two minutes when a #5807 service bound for Hsinchu TRA Station appeared — and I couldn’t remember the last time a bus seat had felt so comfortable.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide and co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the