Oct 31 to Nov 6

Chang Chang-mei (張常美) was just 19 years old when she was suddenly summoned out of class, led into a jeep and thrown in a small cell. “Isn’t this where they put bad people?” she thought.

Later that day, the guards dragged in two of her male classmates. Chang wept until the sun came up, but this ordeal on April 10, 1950, was just the beginning of the nightmare.

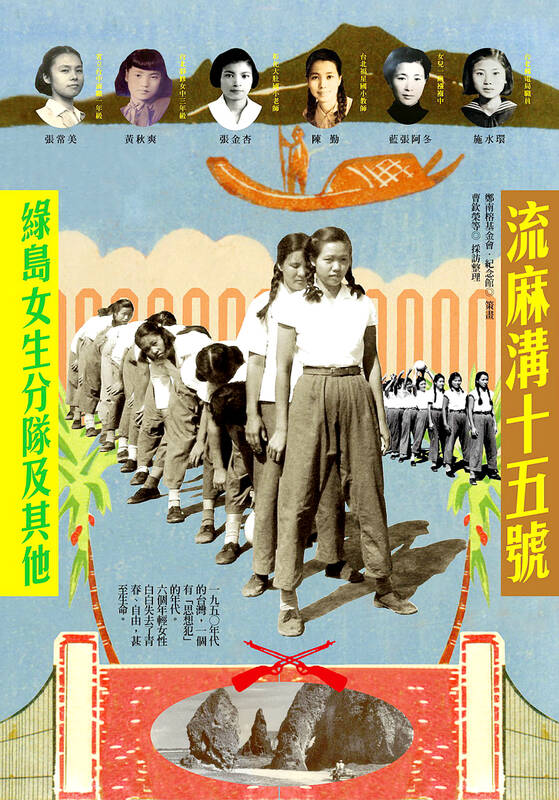

Photo: File photo

Months later, Chang found out that she was arrested because the leader of her school’s student government, of which she was an officer, was accused of being a communist. Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) agents made the terrified Chang sign a confession under a blinding light in a room filled with torture devices, and was sentenced to 12 years for joining a seditious organization — a common charge during White Terror.

“I was just a 14, 15-year-old girl when I joined the student government,” she recalls in the 2012 book, Liumagou No. 15 (流麻溝十五號). “I didn’t join the [KMT], nor did I join the communist party. I just wanted to get an education, I didn’t care about those things.”

Chang spent time in several facilities before landing on Green Island in 1953. She was referred to as No. 72, one of roughly 100 women who made up the often-forgotten female division of political prisoners on the island. Their ordeal of forced labor, torture and “re-education” is featured in the new film Untold Herstory (流麻溝十五號), which hit the theaters on Friday.

Photo courtesy of Activator Marketing Co

The fictional plot is based on the book, which details the experiences of six female political prisoners, four of whom spent time on Green Island. The book’s final character, Shih Shui-huan (施水寰), was the only one who did not make it out alive; her tragic story and execution was featured in the June 18, 2021 edition of “Taiwan in Time.”

LIFE ON THE ISLAND

Chang had already seen and experienced much suffering and hardship by the time she arrived on Green Island. Her cell in the first facility was next to the interrogation rooms, and she could clearly hear men being beaten and tortured all night.

Photo courtesy of GJTaiwan

She was later held in cramped, unsanitary conditions with other women and children, and recalls inmates giving birth in the cells. Executions took place during the wee hours, and the women would shudder whenever footsteps approached their cell, wondering if they would be the next to go. One of the most harrowing memories was watching crying children cling on to their mothers who were being dragged off to the firing squad.

On Green Island, the prisoners were mostly confined to the fenced living areas, and only let out to attend classes, do laundry and carry water. Some women, mostly from China (“mainlanders”), joined a theater troupe that put on anti-communist performances. They rehearsed in a cave by the shore.

The male prisoners grew vegetables and cooked — Chang recalls that it was the best food she had during her 12 years of imprisonment. Those who broke the rules were often confined to a solitary bunker, where they stayed for months at a time living in their excrement. Many went mad.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

RE-REBELLION CASE

Chang didn’t spend much time in Green Island. She was sent to Taipei at the end of 1953 to stand another trial due to suspected involvement in the infamous “re-rebellion” case (再叛亂案) in the camp, which features heavily in the movie’s plot. She recalls that her arrest was due to letters sent to her by former classmate and fellow prisoner Hsu Hsueh-chin (許學進), who encouraged her to join the passive resistance against the prison’s draconian rules.

The prisoners were particularly adverse to the “One Person, One Heart, Save the Country with Good Conscience Movement” (一人一心良心救國運動), which involved tattooing anti-communist slogans on their bodies.

Chang was terrified and immediately destroyed the first letter, but the second was intercepted by prison authorities. She insisted that the first note was a love letter, which she ignored because she was not in the mood for romance in jail, and that she had no idea what the second one was about.

The prisoners didn’t talk much with each other, Chang recalls, as snitching was common. Hsu was caught because a close friend of his reported his behavior to the guards.

Chang was sure she was going to die.

“I got 12 years without any evidence, what are they going to do now that there is evidence?” she wondered.

Fortunately, she was acquitted. Fourteen people, including Hsu, were executed for this incident, their death warrants personally signed by KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石).

The lone woman executed in this ordeal was Fu Ju-chih (傅如芝), with whom Chang spent time on Green Island. According to Chang, she was nabbed for failing to copy down the parts of her “political education” textbooks that criticized communism. But what really got her killed were the letters she exchanged with the incident’s main suspect, Chen Hua (陳華), which she hid under the cap of a hot water bottle. Someone must have notified authorities because the guards knew immediately where to look when they entered the cell. Fu was just 23 years old.

Chang remained in a correctional facility until her release in 1962. A few years later, she married Ouyang Chien-hua (歐陽劍華), a fellow prisoner whom she met at her last stop, and after much initial hardships, the two were able to cobble together a decent life with four children.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she