Among the proselytizers, merchants and adventurers from Europe who inserted themselves into Taiwan’s early modern history, George Psalmanazar is notorious. Centuries before the Chinese Communist Party began faking news about Taiwan, this (most likely) French-born hoaxer, who claimed to be a Formosan and invented his own language to prove it, was regaling eighteenth century London with tales of annual mass sacrifice, floating villages and laws permitting the cannibalization of adulterous wives.

While Psalmanazar later admitted his fraud and actually helped to edit genuine accounts of Taiwan, his real name, birthplace and other key details of his life remained a mystery. It wasn’t until 1968 that the first comprehensive account of The Great Formosan Impostor was published.

The book’s author, Father Frederic Foley, made a valuable contribution to documenting Taiwan’s postwar history. In several curious ways, Foley’s life parallels the subject of his biography — most obviously in the pair’s shared Jesuit background. Yet, unlike Psalmanazar, who is well-known among Formosaphiles, Foley remains relatively obscure.

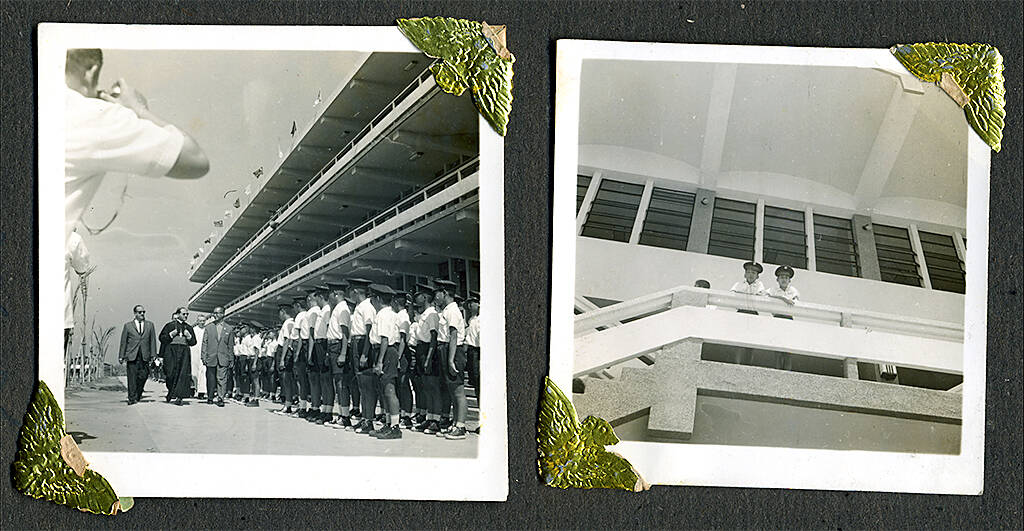

Photo courtesy of Joseph Ho

Joseph Ho (賀威瑋), an assistant professor of history at Albion College in the US state of Michigan, is in the process of rectifying this. Following the publication in January of Developing Mission, his monograph on photography and filmmaking among American Protestant and Catholic missionaries in China, Ho gave an online talk Oct. 13 that cast light on the work of Foley and his fellow Jesuits in Taiwan.

Hosted by the University of Nottingham’s Taiwan Studies Program, the Webinar was titled Framing Futurity: Photography, Religious Diaspora, and Transnational Imaginations of Cold War Taiwan. The presentation was split into two parts, the first of which focused on Foley’s dual role as a missionary and maker “of extremely high-quality photojournalist images.”

Picking up the strands of Developing Mission, Ho looks at “missionary modernity” and posits a shift toward “Christian arcs of containment.” The idea of an “arc of containment,” advanced in a 2019 work of the same name by Singaporean scholar Ngoei Wen-qing, refers to the crescent of anticommunist states in Southeast Asian that emerged from the confluence of British neocolonialism, anti-Chinese sentiment and burgeoning US hegemony in the region.

Photo courtesy of Joseph Ho

While this development has typically been viewed through a political lens, Ho reframes this to ask: “What does it mean when Christian actors are thinking about their reframing of identity within and without political issues of the arc of containment?”

BLENDED IDENTITIES

Considering the theme of “wayfaring” in the work of photographer Chang Chao-tang (張照堂), which formed the basis of an exhibition last year in Australia on Taiwanese photography, Ho poses several more questions: “Where are we going? How are we finding our path? And what kinds of roots are being set down as part of these experiences and visual materials?”

Photo courtesy of the Foley Collection, Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History, Boston College

Wayfaring among diasporic Chinese, which features in such works as Dominic Yang’s The Great Exodus from China (2021), is extended to include the displacement of the missionaries.

Having prepared himself for missionary life in China, Foley is transplanted to Taiwan, where he undergoes “a greater reframing of the mission to which he belonged.” With the 1959 publication of The Face of Taiwan, Foley begins “blending the identity of a photojournalist with the identity of a missionary priest.”

As such, Foley is “not just a kind of mediator between the United States and Taiwan or between Catholicism and the world; he is also a photographic mediator.”

Photo courtesy of the Foley Collection, Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History, Boston College

PHYSICAL INTERACTION

Ho says visual technologies and materials have agency.

“Images do things and cameras do things, and together shape micro-historical engagements. They’re involved in lived experience,” he says.

Photo courtesy of Joseph Ho

He notes that to shoot with the Rolleiflex 3.5E camera that Foley used, you had to “curl yourself into a ball” to look down into it.

“There is a performance that is structured by the device that actually puts the photographer, in this case a missionary photographer, in a submissive posture,” Ho says. “That does something to the relationship between the subject, the maker and the audience.”

In the second part of the discussion, Ho spotlights a personal photo collection, which documents generations of a diasporic Chinese Catholic family that Ho eventually reveals as his own. Calling these images “relational memory maps,” he suggests they “represent imagined belonging.”

The albums, says Ho, become a “physical and visual assemblage of material that maps out what it means to set down roots.”

Even blurred images and spaces where photos have been removed or added tell their own story.

“There’s a sense of negotiating absences and technical problems in the evolution of the album.”

At several points in the presentation, Ho draws on Roland Barthes’ seminal work Camera Lucida (1980).

“The photograph is always something that has been,” Barthes writes. “It doesn’t necessarily say what is no longer, but only and for certain what has been.”

Emphasizing this point, Ho also quotes Susan Sontag’s description of photos as “memento mori” that “testify to time’s relentless melt.”

Tweaking this, Ho calls photos “memento vivere,” that remind us to live.

As per the title of the talk, futurity and “afterlives” are embedded within the lived experiences of photographic images. As much as they capture the past, images, Ho says, are also about “looking at the future, thinking ahead and moving forward with materialized visual imagination.”

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

Desperate dads meet in car parks to exchange packets; exhausted parents slip it into their kids’ drinks; families wait months for prescriptions buy it “off label.” But is it worth the risk? “The first time I gave him a gummy, I thought, ‘Oh my God, have I killed him?’ He just passed out in front of the TV. That never happens.” Jen remembers giving her son, David, six, melatonin to help him sleep. She got them from a friend, a pediatrician who gave them to her own child. “It was sort of hilarious. She had half a tub of gummies,

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping

There is an old British curse, “may you live in interesting times,” passed off as ancient Chinese wisdom to make it sound more exotic and profound. We are living in interesting times. From US President Donald Trump’s decision on American tariffs, to how the recalls will play out, to uncertainty about how events are evolving in China, we can do nothing more than wait with bated breath. At the cusp of potentially momentous change, it is a good time to take stock of the current state of Taiwan’s political parties. As things stand, all three major parties are struggling. For our examination of the