Oct. 10 to Oct. 16

Caitian Fudi (采田福地, “blessed land of colorful fields”) seems to just be a poetic name for a typical family shrine in Hsinchu’s Jhubei City (竹北). But the name hides its true identity: combine the first two characters and you get fan (番, “savage”), the term used during the Qing Dynasty and Japanese colonial era for Taiwan’s indigenous people.

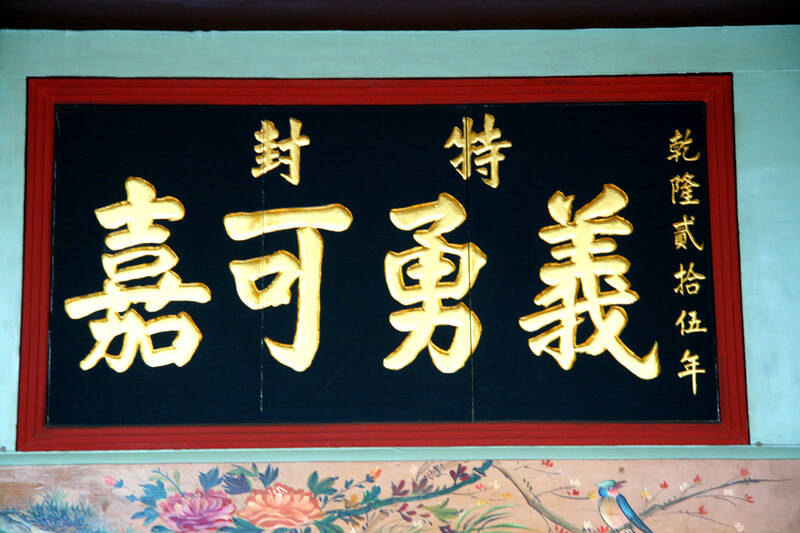

The shrine was originally built in 1797 to honor the seven main families of the indigenous Taokas territory of Jhucian (竹塹), which was based around today’s downtown Hsinchu City. Qing policies and Han immigration starting in the early 1700s severely eroded their culture and way of life, but they still persevered as a loose community until warfare between rival Han groups in the 1850s ravaged their lands and caused them to scatter.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The shrine was destroyed in the unrest, but in 1878 the remaining five families got together to rebuild it, renaming it Caitian Temple (采田宮). Even though they had mostly assimilated into Han culture, they still gathered here twice a year to worship their ancestors using the Taokas language.

A stele explains the migration history of the Jhucian Taokas, how they accepted Qing rule, and were rewarded for helping suppress local rebellions. In 1758 (some say 1788) the Qing governor of Taiwan ordered the Taokas to adopt the Qing hairstyle and Han dress, and gave the seven main families the surnames Liao (廖), Chien (錢), San (三), Wei (衛), Pan (潘), Li (黎) and Chin (金). No descendants of the Li and Chin can be found today.

The last person who knew the words to the Taokas-language ceremony died in 1966, and rituals have been carried out in the Hakka language ever since. Today the shrine also hosts cultural activities as well as exchanges with other Pingpu (plains indigenous) groups.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ARRIVAL OF HAN SETTLERS

Last week’s Taiwan in Time column explored the life of Huang Shih-chieh (黃世傑), who led the first Han settlers into Jhucian territory and triggered waves of massive Han immigration. Although things were reportedly peaceful at first, the Taokas quickly became marginalized due to the loss of their original way of life, and were either forced out of the area or assimilated into Han culture.

The Qing gave them special rights as “cooked savages” (熟番) who were considered more civilized and subservient to the government, and the seven families continued to do fairly well until the mid-19th century. This week’s column explores what life was like for these Taokas, who despite adopting Han culture, retained aspects of their identity and ancestral memory.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Records show that the traditional territory of the Jhucian Taokas stretched from Yanshuei River (鹽水溪) in southern Hsinchu County to Shezi River (社子溪) in southern Taoyuan City.

After Wang established two extensive settlements in today’s Hsinchu City area, in 1732 another group founded Maoerding Village (貓兒錠). The land contract explains that the Taokas were having trouble paying their taxes (which were heavier than those paid by the Han settlers) due to the decline of deer in the area, and they also didn’t have enough funds to build proper irrigation systems to farm. The contract stated that it was better that the land was farmed by the Han, who would pay the Taokas’ taxes. Much land was acquired this way, taking advantage of the Taokas’ hardships.

The Qing eventually reduced taxes for the Taokas who took up farming, and they banded together in the Han-type settlement of Jhucian. It was officially designated a she (社), which indicates an indigenous village. They were allowed to settle in an area between the Han settlements and the hostile “raw barbarians” further to the east, and Han settlers were forbidden from encroaching. They were also granted special tax-free land renting rights in these areas.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The village remained in the Hsinchu City area until 1749, when floods forced them to relocate northward to the Jhubei area. About 400 Taokas thrived here as hunters and farmers, and they expanded to the east and north while renting much land to Hakka settlers.

ASSIMILATION

At first, Han interpreters served as go-betweens to the Taokas chiefs and Han leaders. There are cases of them abusing their power and seizing indigenous land, but they were important figures to both communities. By 1753, enough Taokas had learned Chinese that they took on the position themselves. They started commonly using Han surnames around this time but retained their indigenous names; these later morphed into hybrid names and only became fully Han in the 1800s.

After helping the Qing quell the Lin Shuang-wen (林爽文) rebellion in 1788, many Taokas were enlisted as civilian guards and were given land to farm around their posts in the foothills to the east.

Wei A-kuei (衛阿貴) founded Sinsing Village (新興庄) in today’s Guansi Township (關西) under this system around 1794, and invited large numbers of Hakkas to help farm the land. Stuck between the powerful Hoklo by the coast and hostile indigenous in the mountains, Taokas often worked with Hakkas, and the two often teamed up together to help the Qing defeat Hoklo rebels. There was much intermarriage between the two groups, speeding up the cultural loss.

This was the last wave of Taokas expansion, and things started to go downhill for them in the 1800s.

LOSING THE LAND

Government protection toward “cooked savages” started to wane under the Jiaqing Emperor, who took the throne in 1796. Between 1796 and 1850, the Taokas lost a great deal of land in the reserved zone to Han settlers. Lacking capital and manpower, they were also burdened by taxes and duties as border guards, and they could no longer compete.

Much of the land was lost as collateral as they borrowed money from Han loan sharks and were unable to pay it back due to high interest rates. In addition, many Taokas landowners permanently lost their lands to the Han farmers because they could not pay back the deposit when the contract was up. Other lands were lost by more dubious means.

Interestingly, future Taokas chief Wei Pi-kuei (衛壁奎) sold his house and land to a Han farmer to fund his trip to the capital to take the imperial examinations. The final decades of Qing rule were chaotic due to heavy fighting between rival Han settlements, and the Taokas scattered further.

The final blow was the Japanese revoking their renting rights in 1904. Since there was no more benefit to identifying as indigenous, many registered as Han during the following colonial census to avoid discrimination. Young people sought opportunities in other areas, blending into Hakka society as “Pingpuke” (平埔客).

Despite their dispersal, descendants of the seven families never forgot to worship their ancestors at Caitian Fudi. Today, they have clan associations in the Taoyuan, Hsinchu and Miaoli areas, as well as Taipei and Kaohsiung.

Per Han tradition, the seven families kept detailed genealogy books, which often emphasized Confucian values. Their indigenous identity is apparent, if not explicit, through the family histories. For example, a Chien family book from the early 1900s states that they only learned the importance of family names and ancestor veneration after they “received” the seven surnames. It also notes that their original home was a she — only used for indigenous villages.

It gets more specific as time passes: the Liao family book from 1973 states, “Our ancestors are fan (“savages”), and only during Cheng Cheng-kung’s (鄭成功) rule of Taiwan did we submit to the Chinese, began using Chinese surnames and intermarried with Chinese.”

Many Jhucian descendants interviewed in the book Modern Self Identities of the Pingpu People of Jhucian Village (當代平埔竹塹社的族群認同) state that while they identify as Hakka, they know they have indigenous ancestry, but don’t know which exact people.

Recent publications spell things out clearly. The Wei family book published in 2000 begins with: “The ancestors of the Weis are indigenous Pingpu Taiwanese … Taokas who lived in the Hsinchu area.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

It’s Aug. 8, Father’s Day in Taiwan. I asked a Chinese chatbot a simple question: “How is Father’s Day celebrated in Taiwan and China?” The answer was as ideological as it was unexpected. The AI said Taiwan is “a region” (地區) and “a province of China” (中國的省份). It then adopted the collective pronoun “we” to praise the holiday in the voice of the “Chinese government,” saying Father’s Day aligns with “core socialist values” of the “Chinese nation.” The chatbot was DeepSeek, the fastest growing app ever to reach 100 million users (in seven days!) and one of the world’s most advanced and

The latest edition of the Japan-Taiwan Fruit Festival took place in Kaohsiung on July 26 and 27. During the weekend, the dockside in front of the iconic Music Center was full of food stalls, and a stage welcomed performers. After the French-themed festival earlier in the summer, this is another example of Kaohsiung’s efforts to make the city more international. The event was originally initiated by the Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association in 2022. The goal was “to commemorate [the association’s] 50th anniversary and further strengthen the longstanding friendship between Japan and Taiwan,” says Kaohsiung Director-General of International Affairs Chang Yen-ching (張硯卿). “The first two editions

It was Christmas Eve 2024 and 19-year-old Chloe Cheung was lying in bed at home in Leeds when she found out the Chinese authorities had put a bounty on her head. As she scrolled through Instagram looking at festive songs, a stream of messages from old school friends started coming into her phone. Look at the news, they told her. Media outlets across east Asia were reporting that Cheung, who had just finished her A-levels, had been declared a threat to national security by officials in Hong Kong. There was an offer of HK$1m (NT$3.81 million) to anyone who could assist