Aug. 22 to Aug. 28

Max Liu (劉其偉) wanted to become a pirate when he was young. After reading Treasure Island, he dreamed of commanding a great ship and exploring the vast world, writes Yang Meng-yu (楊孟瑜) in Liu’s biography, Ever Changing Max Liu (百變劉其偉).

Such aspirations are mere childhood fantasy for most people, and although born into a wealthy family, Liu’s turbulent early life left him struggling to make ends meet.

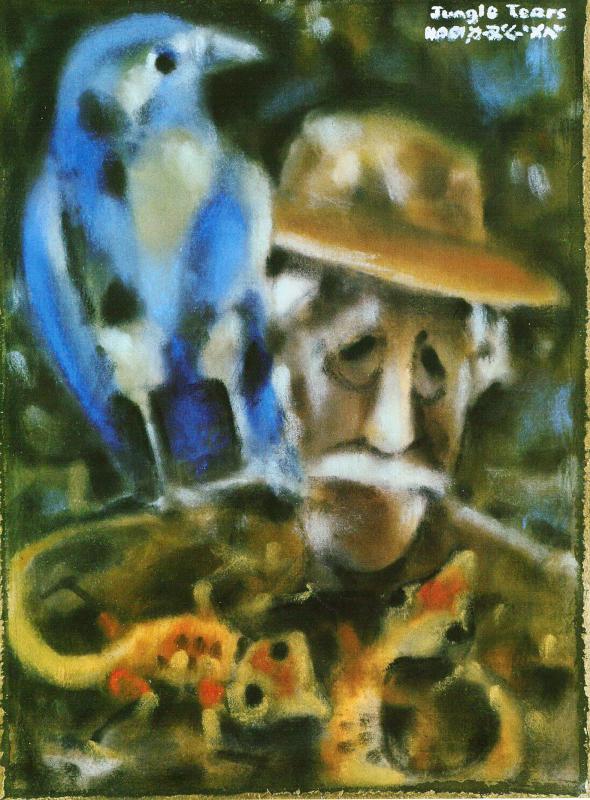

Photo: Lee Jung-ping, Taipei Times

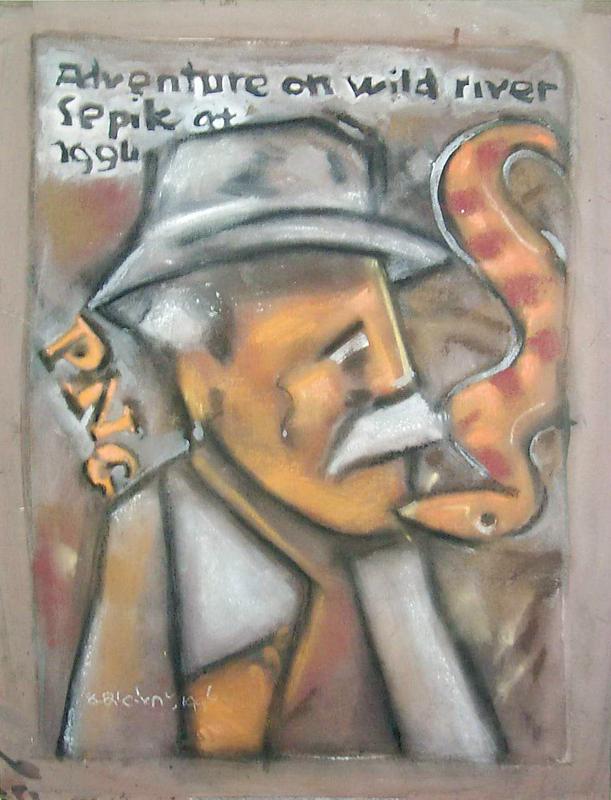

Upon retiring in 1971, however, Liu became a full-time artist and amateur anthropologist, traveling to the less-developed areas in Borneo, Africa, Central America and other places where he developed a fascination for indigenous arts and culture.

Liu produced numerous publications and held countless exhibitions, and became a tireless champion of environmental conservation. He traveled until his health no longer permitted it, embarking on his final trip to Papua New Guinea at the age of 81.

First arriving in Taiwan in 1945 as a technician for the new government, Liu settled here after the Chinese Civil War. His ordinary life began to change when he suddenly took up painting at the age of 38. He was pretty good at it too.

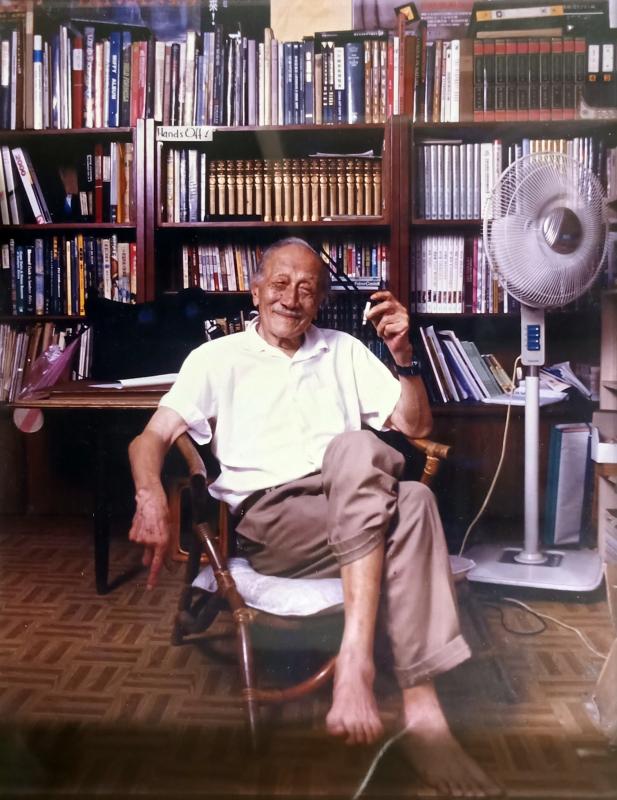

Photo: Wang Chu-hsiu, Taipei Times

But to Liu, the turning point came in 1953 when he was hired by the US Army during the Vietnam War. Although it was a financial decision, he finally had the chance to become an explorer, visiting places like Angkor Wat and the ruins of the Kingdom of Champa. He published a book on his findings as well as a collection of paintings inspired by local culture.

‘INFERIOR AND POOR’

Liu’s mother died shortly after giving birth to him on Aug. 25, 1912. He still enjoyed a privileged life in Fuzhou, China until the age of six, when World War I caused his family’s tea export business to go bankrupt.

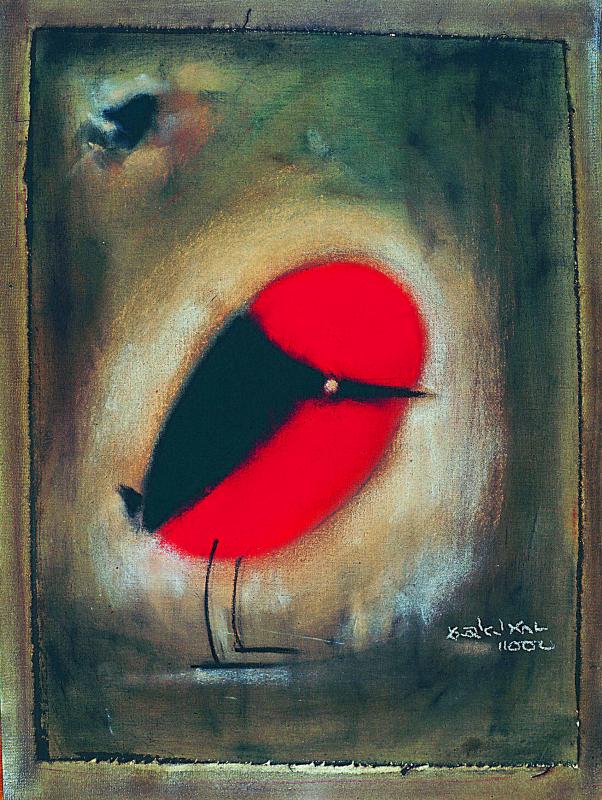

Photo: Lee Jung-ping, Taipei Times

After selling off their prized posesssions, the family moved to Japan in 1919 for a new start. They were living in Yokohama when the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake struck the area, and Liu recalls being suddenly violently thrown to the ground while walking home from school. When he came to, the buildings around him had been flattened and dust clouds obfuscated the sky. The family lost everything again, but fortunately they all survived.

These experiences, along with racism in Japan, had turned Liu into a fight-happy, angsty young man by the time he entered Kobe English Mission College. The only reason his father sent him there was because it was free, but Liu was able to learn English, which proved beneficial for his future endeavors.

Liu received a scholarship to study electrical engineering at the National Railway Technical College — he recalls that the main reason he chose this path was due to less less competition for financial assistance. He returned to China to work afterward, but was fired from his first job due to bad behavior.

Photo: Ling Mei-hsueh, Taipei Times

“People become angry and violent usually because they feel inferior or because they are poor, and I was both,” he recalls. Things changed after he got an assistant teaching job at Zhongshan University in Guangzhou, as the academic atmosphere there helped ground him and calm him down.

DARED TO PAINT

Liu’s life was thrown into chaos again by the Second Sino-Japanese War, and he was recruited into the army due to his knowledge of Japanese. He was stationed along the Yunnan-Burmese border, where for the first time he encountered minority cultures and landscapes that he had never even heard of before. The gregarious Liu visited their villages, and decades later he could still remember the taste of the leaf-wrapped rice cake they offered him.

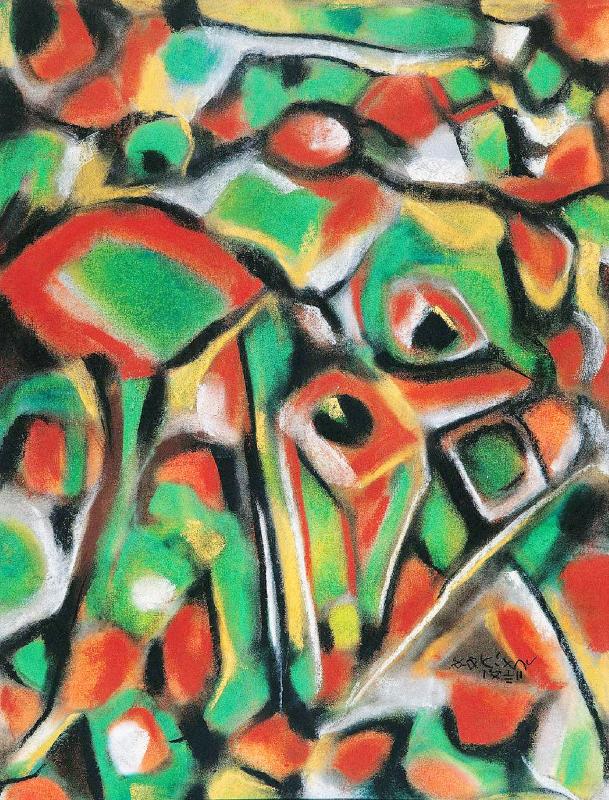

Photo: Chen Wei-jen, Taipei Times

“I did not know what ‘indigenous’ meant then, and I had no anthropology training, I was just in awe and very excited,” he recalls. “I just liked these people.”

In 1949, Liu was working in Taiwan when he stumbled across an art exhibition at Taipei’s Zhongshan Hall. The first thing he noticed wasn’t the art, but the high asking prices for each piece. His friend told him that the artist was an engineer: “You’re also an engineer, why don’t you paint?” the friend teased.

Liu immediately headed to the art supply store. He was 38 years old by then, and his first subject was his infant son. He obviously had a talent for it, as he was selected to the 1950 Taiwan Provincial Art Exhibition and hosted his first solo show two years later.

Photo: Chen Feng-li, Taipei Times

Liu was also a prolific writer — he says he started doing it primarily to supplement his income — but it soon became another one of his many passions.

In 1965, a financially struggling Liu secretly applied to work for the US Army during the Vietnam War. His friends and family tried to stop him to no avail when they found out, but he was adamant on going to provide a better living for his family, saying he would rather die in a war than be poor.

His higher salary — seven times as much as what he made in Taiwan — allowed him to buy more materials to experiment with, and his new surroundings provided much inspiration despite the horrors of war that he witnessed. Two years later, he returned to Taiwan with more than 200 paintings, showing about a quarter of them at an acclaimed exhibition.

Photo: Huang Ming-tang, Taipei Times

LIMPING EXPLORER

At the age of 60, Liu retired and became a full-time explorer. His first stop was the Philippines, which resulted in the book Culture and Art of Philippine Minorities (菲島原始文化與藝術), and later headed to South Korea, Central and South America, Borneo and South Africa.

Liu also paid much attention to Taiwan’s indigenous cultures, investigating the slate house of the Paiwan in Pingtung, as well as the Atayal in Hualien and Tao on Orchid Island.

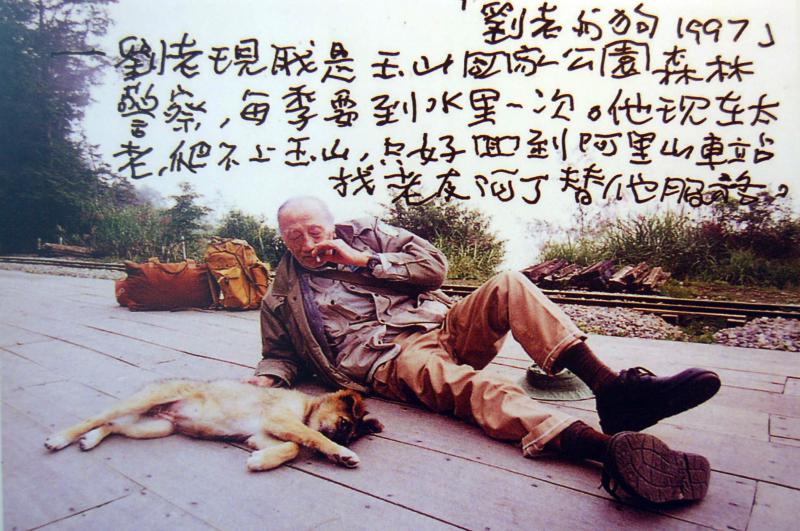

It was not easy for an old man to traverse through the jungles. A 73-year-old Liu was suffering from arthritis when he arrived in Borneo for the second time. Despite limping for much of the trip, he didn’t hesitate getting out of the boat to help push when they hit a dry patch.

“It was him who inspired us to make it to the deepest village,” a companion recalls, noting that few outsiders had been there. It was hot, humid and dangerous, and at one point they had to pull a Swiss reporter out of quicksand, but Liu did not fear death.

Once, someone asked Liu, “Are there really cannibals in Africa?” He replied, “No, the cannibals are all in Taipei.”

Liu’s final trip was to Papua New Guinea, accompanied by his youngest son. He remained humorous about his condition when watching the footage: “I was like, ‘Who is that old man walking so slowly? Oh, it’s actually me.’” He brought back dozens of artifacts, which were exhibited at the Natural Science Museum in Taichung.

Although Liu was no longer able to explore, he remained a passionate wildlife and environmental conversationalist, publishing numerous articles on the topic. His continued to write and paint, and his final book was Eroticism in Literature and Art (性崇拜與文學藝術), published the year of his death in 2002.

Liu insisted that he was an amateur until the end: “I’m not an artist, I’m not an anthropologist,” he told NTU students at a lecture. “I was just playing around. But I played so hard I made a name out of it.

“If you want to do something, do it seriously! Otherwise, you’re better off going home and sleeping.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The Taipei Times last week reported that the rising share of seniors in the population is reshaping the nation’s housing markets. According to data from the Ministry of the Interior, about 850,000 residences were occupied by elderly people in the first quarter, including 655,000 that housed only one resident. H&B Realty chief researcher Jessica Hsu (徐佳馨), quoted in the article, said that there is rising demand for elderly-friendly housing, including units with elevators, barrier-free layouts and proximity to healthcare services. Hsu and others cited in the article highlighted the changing family residential dynamics, as children no longer live with parents,

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,

I was 10 when I read an article in the local paper about the Air Guitar World Championships, which take place every year in my home town of Oulu, Finland. My parents had helped out at the very first contest back in 1996 — my mum gave out fliers, my dad sorted the music. Since then, national championships have been held all across the world, with the winners assembling in Oulu every summer. At the time, I asked my parents if I could compete. At first they were hesitant; the event was in a bar, and there would be a lot