Unlike Transitions in Taiwan, the previous White Terror-themed collection from Cambria, this latest anthology addresses Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) crimes head on.

In Wu Chuo-liu’s (吳濁流) almost novella-length “Potsdam Section Chief,” for example, the depiction of protagonist Fan Hanzhi’s wanton venality is unvarnished. He is shown as a traitor, informer, thief and racketeer. Lest the reader be left with the impression that Fan is an aberration, a lone wolf operating within an otherwise virtuous milieu, the story’s conclusion paints an even more disturbing picture.

Following Fan’s arrest, the investigator who tracks him down in Taiwan after a year-long search, is horrified to see his quarry’s avaricious cunning reflected in the responses of his own team.

“His secretary walked in with a grin and congratulated him for nabbing Fan. The grinning face looked just like Fan’s. Then he saw that everyone in the office, even the janitor, was grinning like that, their faces the spitting images of the traitors and corrupt officials … It was loathsome.”

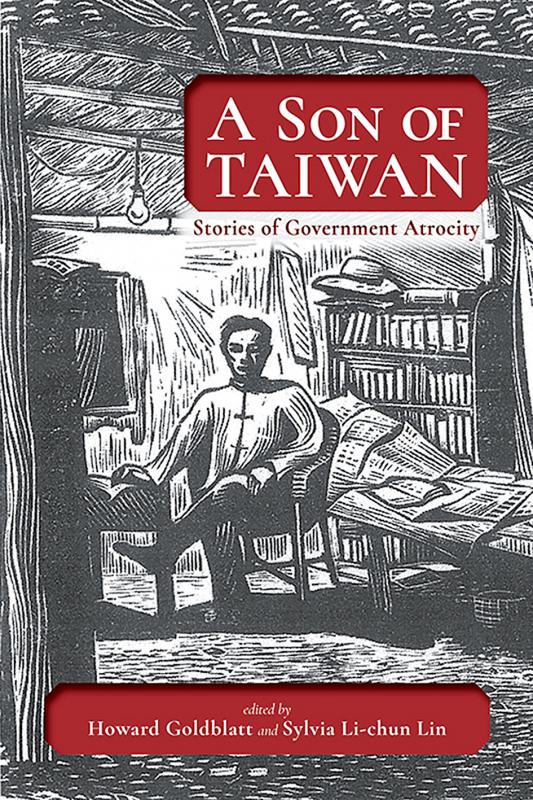

A montage of vignettes from Jian A-tao, A Son of Taiwan, the tale from which this collection takes its name, gives us a personal view of how Taiwan’s intelligentsia suffered under the KMT’s authoritarian rule. Loosely based on the experiences of the writer Yeh Shih-tao (葉石濤), the series of fragments begins with the protagonist A-tao’s incarceration.

Joined in his cell by a group of peasants, who have been arrested as suspected Communists during the Luku Incident (鹿窟事件) of 1952 to 1953, Jian reflects that the new inmates “were clearly not the sort who commit political crimes.”

Another cellmate, Professor Wang sums it up. “They’ll arrest anyone. This time they even pulled in a bunch of destitute farmers. Bastards!”

Yet, upon quizzing an elderly member of the group, A-tao begins to suspect that things might not be so simple. The apparently “guileless” old fellow seems a little too innocent, and A-tao recalls that diehard communists are “adept at disguising themselves.”

The farmers also relate the death of A-tao’s famous contemporary, the writer Lu He-ruo (呂赫若), an avowed communist who disappeared during the crackdown (and is thought to have died from a snakebite). Again, we are reminded that the tentacles of repression extend to all segments of society.

The subsequent episodes deal with A-tao’s life after his release — blacklisted and drifting from one menial position to another, shunned by friends, embarrassed by a chance encounter with a former flame, and finally dragged back in for questioning. Punishment is shown as all pervasive and perennial, and the occasional act of kindness and encouragement cannot dissipate the fog of despair.

Nowhere is the brutality of the dictatorship more manifest than in Red Butterfly by Lay Chih-ying (賴志穎). Collaborating again with translator Darryl Sterk, who worked on Lay’s own short story collection Home Sickness in 2020, the Montreal based writer is, at 41, by far the youngest author in this anthology.

Lay’s narrator is a medical student who finds himself dissecting the corpse of his “disappeared” cousin. In flashback sequences, Lu He-ruo makes another appearance as the missing youth’s music teacher and, it soon becomes clear, recruiter. Carefree reminisces give way to the shock of arrest and interrogation, as the narrator reveals he was unaware of the clandestine sedition.

Addressed to his presumably murdered relative, the narrator’s reflections are interspersed with clinical, present tense observations of the various incisions he is making made on the lifeless body, creating a poignant, yet disconcerting juxtaposition.

The menace of violence permeates Auntie Tiger, a story that blends fact, fiction and Taiwanese folklore to depict another historical figure, Hsieh Hsueh-hung (謝雪紅). This legendary revolutionary, who led the ill-fated 27 Brigade uprising in Taichung in 1947, emerges as a multifaceted feminist symbol in writer Li Ang’s (李昂) imagining: good-time girl, guerrilla leader, and, overarchingly, fairy-tale witch, with a strong dash of dominatrix. (The first-person sex scenes, it must be said, are jarringly incongruous and unappealing.)

References to the KMT’s “killing zones” aboard trains, the 228 “appeasement massacre” engulfing the island, and “relatives, neighbors, friends, and local gentry who were imprisoned, executed, or went missing,” are unambiguous in their condemnation of the regime.

Yet for all that, the absence of explicit depictions of state violence in this collection makes the subtitle “Stories of Government Atrocity” a trifle baffling.

Of course, said absence is understandable. As the collection’s co-editor Sylvia Li-chun Lin (林麗君) notes in the introduction, “ambiguity was a necessary narrative technique in literary works when representing atrocities in Taiwan.” Many of the characters in these stories are unsure what fate has befallen their missing loved ones, where they are, or how such things came to pass.

Perhaps, then, this is the point: Atrocity exacted by a totalitarian regime will necessarily remain enveloped in uncertainty, making it that much more harrowing. This is a legacy with which Taiwan continues to wrestle, and these stories — for the most part — do an admirable job of conveying that.

Finally, where this selection really shines is in the realms of the metaphorical and allegorical. In “Potsdam Section Chief”, for example, there is the none-too-subtle but superbly effective use of Fan and his wife Yulan’s relationship to allude to Taiwan’s disillusionment with “China.”

In Tiger Auntie, the figure of Hsieh is used to highlight KMT hypocrisy — Snow Red as her name literally translates — is a hussy for donning a slit-to-the-thigh qipao, while on First Lady Soong Mei-ling (宋美齡) the garment is elegance personified.

Meanwhile, the brutality of the police who “could take us away from our home, our parents, and our playmates and [they] could even shoot us dead” is somehow transferred onto Hsieh, around whom a terrifying silence looms. Parents deny her existence. Children dare not speak her name.

This, and other provocative metaphors and devices make for a captivating read, which will be a welcome addition to the bookshelves of any fan of contemporary Taiwanese history and literature.

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

The latest edition of the Japan-Taiwan Fruit Festival took place in Kaohsiung on July 26 and 27. During the weekend, the dockside in front of the iconic Music Center was full of food stalls, and a stage welcomed performers. After the French-themed festival earlier in the summer, this is another example of Kaohsiung’s efforts to make the city more international. The event was originally initiated by the Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association in 2022. The goal was “to commemorate [the association’s] 50th anniversary and further strengthen the longstanding friendship between Japan and Taiwan,” says Kaohsiung Director-General of International Affairs Chang Yen-ching (張硯卿). “The first two editions