In a small room thick with incense, a woman in a white headscarf takes communion — a piece of bread dipped in red wine. The man standing next to her holds a red cloth under her chin.

She’s from Russia; he’s from Ukraine. And this sacramental ritual came near the end of a Russian Orthodox Church service in Taichung. As happens nearly every month on the third floor of this nondescript office building, Ukrainians, Russians and others come together for communal prayer.

“I don’t even know who’s Russian and who’s Ukrainian,” congregation member Paul Wollos said. “It doesn’t matter.”

Photo courtesy of Julia Startchenko

Aside from a brief prayer for peace, the topic of war and the lives lost doesn’t come up. The services are completely the same, said Wollos, who grew up Catholic in his native Poland, but later converted to Russian Orthodoxy with its traditional, centuries-old practices.

Wollos said while he misses the beauty of the grand European cathedrals and the echoing voices of the choir within, he’s grateful that Russian Orthodox services are even held in Taiwan.

PRAY FOR THOSE SUFFERING

Photo courtesy of Julia Startchenko

Wearing an ornately embroidered purple robe, symbolic of Lent’s repentance, Father Kirill Shkarbul stood tall before the dozen or so adults and children gathered for Sunday evening liturgy in a space that doubles as a Russian-language classroom.

“We pray for the end of the war in Ukraine and we pray for all of those who are suffering,” said Shkarbul in a deep but softly-spoken tone.

Shkarbul, a 39-year-old Russian Orthodox priest who grew up in and around Moscow, alternates between Chinese, English, Russian and the liturgical language of Church Slavonic during his 90 minute service.

Photo courtesy of Julia Startchenko

Nearly four months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the war has resulted in the deaths of thousands and the displacement of millions. And while the initial shock may have waned, any lingering thoughts of anger or despair simply are not talked about — at least in public.

Instead, the focus of the sermon is on Christ’s compassion and the importance of repentance and daily prayer. Speak less and listen more, Shkarbul implores his congregation, suggesting good deeds such as visiting elderly loved ones or volunteering at hospitals or for church events.

“I try to keep the service focused on the gospel,” Shkarbul said. “We need to keep our personal demons at bay because they deprive us of our peace and freedom.”

Shkarbul recalled the summers he spent as a youth relaxing near the Sea of Azov in Zaporizhzhia in southeastern Ukraine, which was then part of the Soviet Union. The region, known for its historical sites and huge hydroelectric plant, is now the scene of fierce fighting as it finds itself on the front lines of the war.

“There’s just so much hatred now on both sides,” Shkarbul said. For this reason, he added, keeping the politics of the conflict out of his sermons is what’s best for everyone. Personal feelings can be saved for private conversations, he said.

As the only priest serving the Russian Orthodox Church in Taiwan, Shkarbul travels around the island, holding Sunday services in Taipei, Hsinchu, Taichung, Kaohsiung and occasionally Hualien.

Services in Taipei typically attract upwards of 40 people with smaller crowds in other cities. In Taiwan, roughly 1,000 people consider themselves to be Russian Orthodox, Shkarbul estimates.

Following the liturgy, tea and cookies are customarily served. In these relaxed settings, the topics move freely from family and jobs to friendships and the weather.

“We don’t care where we’re from,” said Julia Startchenko, the Russian woman in the white headscarf who took communion.

Startchenko said the Russians and Ukrainians who attend the church services are respectful of each other’s differences and opinions. But it’s their commonalities — religious faith and a desire for peace — that really hold the congregation together.

“We’re all sad,” said Startchenko, who moved to Taichung 22 years ago from the western Russian enclave of Kaliningrad. “Life will never be the same, but we have to learn to live with it.”

Like many other Russians, Startchenko has cousins fighting on both sides of the conflict. Thousands of kilometers away from her family, she has taken it upon herself to promote peace from abroad.

TAIWAN RUSSIAN CLUB

As president of the Taiwan Russian Club, which highlights Slavic culture through activities such as community picnics and dances, Startchenko is an active member of Russia’s expat community.

“I think if you create peace around you it will spread,” Startchenko said.

Singing and dancing to old Russian folk songs — typically about love, family and the joy of life — highlighted a recent picnic hosted by a Russian Orthodox Sunday school. The picnic took place in a rural Taipei park and brought together about 40 people, including both Russians and Ukrainians.

And even at a public event such as this, the topic of war doesn’t arise.

“There’s a time to talk about it, a time to cry and a time not to talk about it,” Startchenko said.

For Elena Nazarova, the time to talk about it is in private conversations with her pastor, Father Kirill, as he’s known to his parishioners. With friends on both sides of the war, she is worried about their safety, especially the ones that live in the Donetsk region of Ukraine.

But at the same time, Nazarova, who grew up near St. Petersburg, supports her native country of Russia. These complicated feelings need to be expressed, she said, adding that she feels better after speaking to someone from the church with a similar cultural background.

Whether they talk about the war with family members or their clergy, both Ukrainians and Russians expressed a need to stop the conflict and needless suffering.

“I can only pray for peace,” said Wollos, the Polish man who converted to Russian Orthodoxy. “We all hope it will be over, but how and when I don’t know.”

The Taipei Times last week reported that the rising share of seniors in the population is reshaping the nation’s housing markets. According to data from the Ministry of the Interior, about 850,000 residences were occupied by elderly people in the first quarter, including 655,000 that housed only one resident. H&B Realty chief researcher Jessica Hsu (徐佳馨), quoted in the article, said that there is rising demand for elderly-friendly housing, including units with elevators, barrier-free layouts and proximity to healthcare services. Hsu and others cited in the article highlighted the changing family residential dynamics, as children no longer live with parents,

It is jarring how differently Taiwan’s politics is portrayed in the international press compared to the local Chinese-language press. Viewed from abroad, Taiwan is seen as a geopolitical hotspot, or “The Most Dangerous Place on Earth,” as the Economist once blazoned across their cover. Meanwhile, tasked with facing down those existential threats, Taiwan’s leaders are dying their hair pink. These include former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), Vice President Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and Kaohsiung Mayor Chen Chi-mai (陳其邁), among others. They are demonstrating what big fans they are of South Korean K-pop sensations Blackpink ahead of their concerts this weekend in Kaohsiung.

Taiwan is one of the world’s greatest per-capita consumers of seafood. Whereas the average human is thought to eat around 20kg of seafood per year, each Taiwanese gets through 27kg to 35kg of ocean delicacies annually, depending on which source you find most credible. Given the ubiquity of dishes like oyster omelet (蚵仔煎) and milkfish soup (虱目魚湯), the higher estimate may well be correct. By global standards, let alone local consumption patterns, I’m not much of a seafood fan. It’s not just a matter of taste, although that’s part of it. What I’ve read about the environmental impact of the

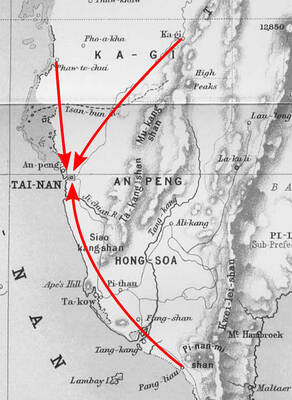

Oct 20 to Oct 26 After a day of fighting, the Japanese Army’s Second Division was resting when a curious delegation of two Scotsmen and 19 Taiwanese approached their camp. It was Oct. 20, 1895, and the troops had reached Taiye Village (太爺庄) in today’s Hunei District (湖內), Kaohsiung, just 10km away from their final target of Tainan. Led by Presbyterian missionaries Thomas Barclay and Duncan Ferguson, the group informed the Japanese that resistance leader Liu Yung-fu (劉永福) had fled to China the previous night, leaving his Black Flag Army fighters behind and the city in chaos. On behalf of the