You’d have to be living under a rock not to know we are in the midst of one of the most devastating pandemics in history. Just how devastating became clear earlier this month when the World Health Organization released a report estimating the global excess death toll due to the pandemic as 15 million — nearly three times the official COVID death count. Other authorities think global excess deaths may be closer to 18 million. These are awfully big numbers, but they pale in comparison with the 1918-1919 Spanish influenza pandemic, which killed an estimated 40 million people — equivalent to about 150 million globally using current population figures.

So, miserable as COVID has been, it is not the “Big One.” According to Bill Gates, that specter awaits us in the not too distant future, which is why we’d be advised to start preparing now.

“It will be tempting to assume that the next major pathogen will be as transmissible and lethal as COVID, and as susceptible to innovations like mRNA vaccines. But what if it isn’t?” he writes in his new book.

It’s a good question. Gates’s proposal, essentially, is that we should do more of what we’re doing already but better and faster. No one can say whether the next pandemic will be caused by a coronavirus, influenza or some pathogen we haven’t considered yet, but with better surveillance systems and laboratory diagnostics we should be able to rapidly identify the culprit and devise medical countermeasures before the outbreak has a chance to spiral out of control.

Most of all, he writes, we need to “practice, practice, practice” by holding regular pandemic exercises and by funding a 2,000-strong team of global pandemic firefighters — Gates, who is fond of acronyms, labels this team Germ, short for Global Epidemic Response and Mobilization.

He does, however, acknowledge that such measures will count for nothing if, having identified gaps in our pandemic response systems, we fail to correct them. In 2016, for instance, Britain’s Exercise Cygnus identified gaps in the UK’s readiness for a flu pandemic, including insufficient stocks of PPE, but no one acted on the recommendations, leaving the UK to beg and borrow PPE from other countries when disaster hit.

Similarly, US planners had long known that mass diagnostics would be crucial in the event of a pandemic. Yet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention failed to roll out COVID tests at anything like the scale required, hampering contact tracing and effective isolation measures. And because of America’s federal system of government, state governors were often unsure who was responsible for what.

The result was that the US suffered one of the highest COVID mortality rates in the world. By contrast, countries such as Singapore, Vietnam and Canada, which had been badly hit by SARS in 2003 and had absorbed the lessons, responded quickly and decisively to Sars-CoV-2, as the coronavirus that causes COVID is known.

So far, so logical. But if preventing pandemics was simply a matter of better logistics and trusting in scientific experts, we would surely have solved the problem by now. That we haven’t is down to the fact that science is full of uncertainties, especially in the early stages of a pandemic when reliable data on the infectivity of a pathogen and its mode of spread may be wanting.

Moreover, scientists are prone to blind spots — in 2014, for instance, few experts thought that Ebola, a virus that had previously caused outbreaks across central Africa, posed a threat to countries in west Africa such as Sierra Leone and Liberia. Similarly, based on the experience of SARS, which was easy for clinicians to spot because those infected became rapidly and noticeably ill, few experts thought that Sars-CoV-2 was capable of asymptomatic spread until it was too late.

In other words, preventing pandemics is as much an epistemological problem as a technical one. We can prepare for known pandemic threats, but so-called Black Swan events are by definition unknowable and unpredictable.

If this problem has occurred to Gates, he does a good job of disguising it. “I am a technophile,” he explains unapologetically. “Innovation is my hammer.”

Nor is he interested in addressing the role of information technology in spreading conspiracy theories about vaccines or misinformation about the effectiveness of lockdowns and mask mandates. This is surprising given that Gates has been accused of using vaccines to plant microchips in unsuspecting populations and is a prominent target for anti-vaxxers. But rather than calling for a rapid reaction team to neutralize fake news about vaccines, Gates ducks the issue, writing that he is confident “the truth will outlive the lies.”

I do not share his optimism. If anything, the experience of COVID demonstrates that conspiracy theories now present a major impediment to the management of pandemics along rational scientific lines. Never mind Germ. What is needed is Dirt — Disinformation Response Team.

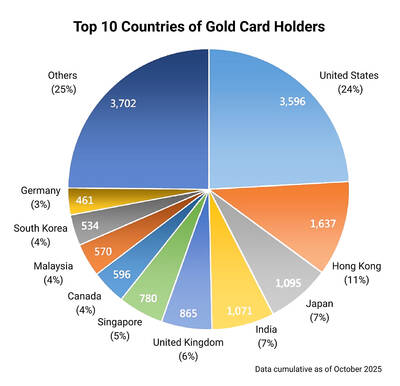

Seven hundred job applications. One interview. Marco Mascaro arrived in Taiwan last year with a PhD in engineering physics and years of experience at a European research center. He thought his Gold Card would guarantee him a foothold in Taiwan’s job market. “It’s marketed as if Taiwan really needs you,” the 33-year-old Italian says. “The reality is that companies here don’t really need us.” The Employment Gold Card was designed to fix Taiwan’s labor shortage by offering foreign professionals a combined resident visa and open work permit valid for three years. But for many, like Mascaro, the welcome mat ends at the door. A

The Western media once again enthusiastically forwarded Beijing’s talking points on Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s comment two weeks ago that an attack by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on Taiwan was an existential threat to Japan and would trigger Japanese military intervention in defense of Taiwan. The predictable reach for clickbait meant that a string of teachable moments was lost, “like tears in the rain.” Again. The Economist led the way, assigning the blame to the victim. “Takaichi Sanae was bound to rile China sooner rather than later,” the magazine asserted. It then explained: “Japan’s new prime minister is

NOV. 24 to NOV. 30 It wasn’t famine, disaster or war that drove the people of Soansai to flee their homeland, but a blanket-stealing demon. At least that’s how Poan Yu-pie (潘有秘), a resident of the Indigenous settlement of Kipatauw in what is today Taipei’s Beitou District (北投), told it to Japanese anthropologist Kanori Ino in 1897. Unable to sleep out of fear, the villagers built a raft large enough to fit everyone and set sail. They drifted for days before arriving at what is now Shenao Port (深奧) on Taiwan’s north coast,

Divadlo feels like your warm neighborhood slice of home — even if you’ve only ever spent a few days in Prague, like myself. A projector is screening retro animations by Czech director Karel Zeman, the shelves are lined with books and vinyl, and the owner will sit with you to share stories over a glass of pear brandy. The food is also fantastic, not just a new cultural experience but filled with nostalgia, recipes from home and laden with soul-warming carbs, perfect as the weather turns chilly. A Prague native, Kaio Picha has been in Taipei for 13 years and