Germans are finding that death no longer quite becomes them. Europe’s biggest economy is rethinking its way of death, with one start-up claiming to have found a way of prolonging life — digitally at least — beyond the grave.

Youlo — a cheery contraction of “You Only Live Once” — allows people to record personal messages and videos for their loved ones, which are then secured for several years in a “digital tombstone.”

Unveiled at “Life And Death 2022” funeral fair in the northern city of Bremen this month, its creators claim it allows users to have their final word before they slip gently into the good night. Traditionally, Lutheran northern Germany has long had a rather stiff and stern approach to death. But as religion and ritual loosened their hold, the crowds at the fair show people are looking for alternative ways of marking their end — a trend some say has been helped by the coronavirus pandemic.

Photo: AFP

“With globalization, more and more people live their lives far from where they were born,” said Corinna During, the woman behind Youlo.

When you live hundreds of kilometers from relatives, visiting a memorial can “demand a huge amount of effort,” she said.

And the COVID-19 pandemic has only “increased the necessity” to address the problem, she insisted.

NO LONGER TABOO

During lockdowns, many families could only attend funerals by video link, while the existential threat coronavirus posed — some 136,000 people died in Germany — also seems to have challenged longtime taboos about death.

All this has been helped by the success of the German-made Netflix series The Last Word — a mould-breaking “dramedy” hailed for walking the fine line between comedy and tragedy when it comes to death and bereavement.

Much like British comedian Ricky Gervais’ hit series After Life, which turns on a husband grieving the loss of his wife, the heroine of The Last Word embraces death and becomes a eulogist at funerals as her way of coping with the sudden death of her husband.

“Death shouldn’t be a taboo or shocking; we shouldn’t be taken unawares by it, and we certainly shouldn’t talk about it in veiled terms,” Bianca Hauda, the presenter of the popular podcast “Buried, Hauda,” said. “It aims to “help people be less afraid and accept death,” she said.

“The coronavirus crisis will almost certainly leave a trace” on how Germans view death, said sociologist Frank Thieme, author of Dying and Death in Germany. He argued that there has been a change in the culture around death for “the last 20 to 25 years.”

These days, there are classes to teach you how to make your own coffin and even people who make a living writing personalized funeral speeches. Digital technology which was “barely acceptable not so long ago” was also beginning to make its mark, he said.

‘STRAITJACKET’

Historian Norbert Fischer of Hamburg University said they have been a shift toward individualism in the “culture of burials and grief since the beginning of the 21st century.”

“The traditional social institutions of family, neighborhood and church are losing their importance faced with a funeral culture marked by a much greater freedom of choice,” he said.

However, the change has been slower in Germany because “legal rules around funerals are much stricter than most other European countries,” said sociologist Thorsten Benkel, which is at odds with “what individuals aspire to.”

Some political parties like the Greens also want to loosen this legislative “straitjacket,” particularly the law known as the “Friedhofszwang.” The 200-year-old rule bans coffins and urns being buried anywhere, but in a cemetery. Originally passed to prevent outbreaks of disease, it has been largely surpassed as a public health measure, particularly since cremation became popular.

Germany also had a very particular relationship with death in the aftermath of World War II. Back in 1967, the celebrated psychoanalysts Margarete and Alexander Mitscherlich put Germany on the couch with their book The Inability to Mourn.

One of the most influential of the post-war era, the book argued that Germans had collectively swept the horrors committed by the Nazis in their name — and their own huge losses and suffering during the war — under the carpet. Thankfully, said Benkel, mentalities have “changed an awful lot since.”

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

The following three paragraphs are just some of what the local Chinese-language press is reporting on breathlessly and following every twist and turn with the eagerness of a soap opera fan. For many English-language readers, it probably comes across as incomprehensibly opaque, so bear with me briefly dear reader: To the surprise of many, former pop singer and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ex-lawmaker Yu Tien (余天) of the Taiwan Normal Country Promotion Association (TNCPA) at the last minute dropped out of the running for committee chair of the DPP’s New Taipei City chapter, paving the way for DPP legislator Su

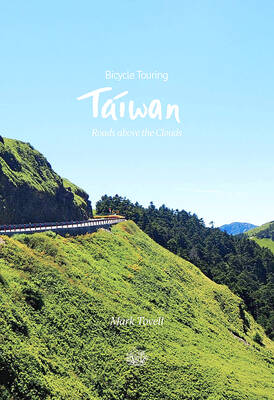

It’s hard to know where to begin with Mark Tovell’s Taiwan: Roads Above the Clouds. Having published a travelogue myself, as well as having contributed to several guidebooks, at first glance Tovell’s book appears to inhabit a middle ground — the kind of hard-to-sell nowheresville publishers detest. Leaf through the pages and you’ll find them suffuse with the purple prose best associated with travel literature: “When the sun is low on a warm, clear morning, and with the heat already rising, we stand at the riverside bike path leading south from Sanxia’s old cobble streets.” Hardly the stuff of your

April 22 to April 28 The true identity of the mastermind behind the Demon Gang (魔鬼黨) was undoubtedly on the minds of countless schoolchildren in late 1958. In the days leading up to the big reveal, more than 10,000 guesses were sent to Ta Hwa Publishing Co (大華文化社) for a chance to win prizes. The smash success of the comic series Great Battle Against the Demon Gang (大戰魔鬼黨) came as a surprise to author Yeh Hung-chia (葉宏甲), who had long given up on his dream after being jailed for 10 months in 1947 over political cartoons. Protagonist