There is absolutely no doubt that this is a really magnificent book.

Scott Ezell previously wrote A Far Corner, about life among wood-carvers in south-eastern Taiwan (reviewed in the Taipei Times April 16, 2015). I rated that an instant classic. Now he has come up with a book about a journey from China’s Yunnan Province, through Sichuan, to Qinghai Province. It begins in Dali and ends in Golmud. He travels by bus, motorbike and hitch-hiking.

A Far Corner was a book without villains, but this new product has modern China as its devil incarnate. It’s the “empire” of the title, though it’s not the only harm-doer. Ezell is undoubtedly aware of the past achievements of the Chinese, especially in science (as Joseph Needham showed in his multi-volume Science and Civilization in China), but modern China is, to Ezell, a destroyer of ecosystems.

Massive dam systems “killed rivers and displaced communities, mountains were raked apart ... and the region was increasingly militarized and surveiled as China tilted towards its grim police state superpower status.”

But the US is another such empire to Ezell. Was it normal in your country to travel so far, a Tibetan asks him.

“Normal? Cheering like a drunken football fan for the army of the country where you were born was normal. Being imprisoned or killed by your own government was normal. Dropping bombs was normal, selling bombs was normal, bombs blowing up children as if it were deplorable, regrettable, reprehensible, but unavoidable and acceptable was normal. Normal was burning the world and sucking the earth from beneath our feet. Normal was a hell-hound on my trail.”

Scott Ezell, an American, stands 198cm tall, he tells us. He has tried corporate work in Taipei, and has lived on an uninhabited islet in Hong Kong harbor. He’s a musician who, in Taiwan’s south-east, made analogue recordings that included the sound of the sea. He is a published poet, but above all he’s a conservationist.

When he discovers that a kind of river dolphin used to swim for 20 million years in the waters of the river he is contemplating until it was exterminated by starving farmers during Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Great Leap Forward, he writes: “Back in Dali, Liu had said ‘Sucks to be a pig’ (they had just watched one being slaughtered). Sucks to be a dolphin too, apparently. Sucks to be a non-human being during the Anthropocene, or a human one if you like living in a world with river dolphins, blue whales, elephants, rhinos, wild tigers, or with living forests, rivers, coral reefs, or breathable air.”

The route north he follows was in part walked by the Long March, but Ezell is not interested in that. Instead, he’s drawn to the amiable Tibetans and even the friendly Han Chinese who were relocated to the region by government fiat. The villains are the government agents constructing dams that will be “square and monochrome, monolithic, right angles and straight lines of utility and decree.”

But not everything’s ugly. This poet sees landscapes of exceptional magnificence and beauty, with a myriad flowers, and a donkey’s cry echoing across the mountainside “like all the broken dreams of men.”

He ends up on the highest and most extensive plateau on earth, half a mile higher than the highest mountain in the contiguous US, and there watches the construction of the railway from Golmud to Lhasa that Swiss engineers had said was an impossibility, but that the Chinese had built anyway. Ezell was first there in September 2004, but revisited the region 20 times before completing this book.

At his highest elevation, some 17,000 feet, he laments that he’s enthralled by such beauty, and such mighty animal migration, but fears he’ll never revisit the place in this lifetime.

Ezell is a philosopher too. “We can explain the complexities of the universe,” he writes, “but the fundamental simplicities are beyond us.”

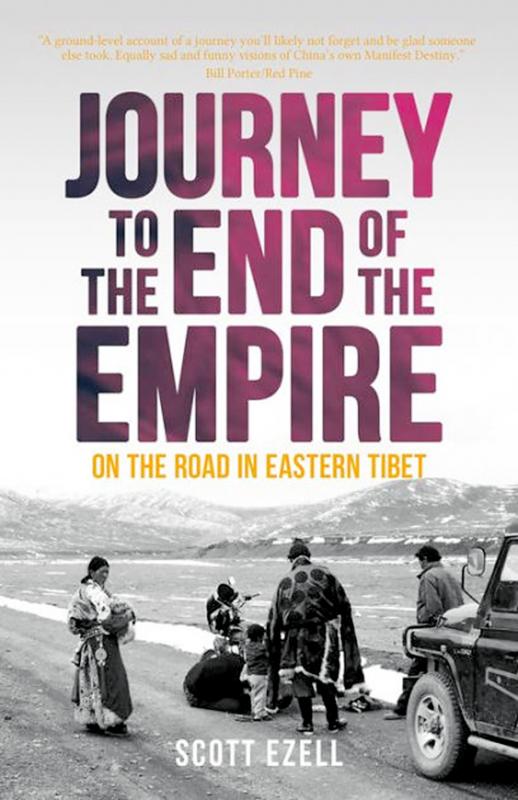

The book isn’t without its sardonic wit either. Baijiu (白酒), the author says, is an adaptable liquid that if you don’t drink it can be used as lighter fuel or paint stripper. The black-and-white photos are idiosyncratic but certainly atmospheric.

At one point he is asked by someone cutting up a yak’s head if they have machines to do such work in the US. He replies that with Jello, Spam, corn flakes and a lot more, yes, they do have machines. This is another example of Ezell using a chance incident to expatiate on wider issues, in this case the degraded nature of much of the American diet.

Up at his highest point, Ezell helps feed orphan antelopes on a reservation. His heart goes out to them, though when a bus full of tourists arrives — all as cold as he is — he feels they can have little sense of the context, the vast distances their herds will have traveled, and will travel again. He’s given a lift down to Golmud by someone who is obliged to pick up some waste from a government site for disposal. No point in trying to refuse, the driver comments.

In Golmud he is strip-searched, or so it would seem — made to bend over a table with his wrists beaten if he tries to resist. Needless to say, this only goes to confirm his dark view of the authorities.

Love is mixed with sadness throughout this fine book, love for the locals he meets and sadness at the conditions they are being forced to endure. His flights of poetry, therefore, tend to be detached from the main drift of the narrative, and were possibly inserted after later visits.

Eastern Tibet isn’t part of Tibet proper, but seems nonetheless to have endured most of the depredations suffered by the central areas. A Buddhist perspective prevails, even so. When he asks a senior lama if the People’s Liberation Army stayed long after they had destroyed the original building, the lama replies it wasn’t long, just 20 years.

And as for the destruction of religious buildings in general, Ezell observes that they are now being re-built, but as gaudy tourist destinations that the original monks are loathe to inhabit.

The author was invariably cold, often hungry and beset by an increasing altitude sickness. He managed to pen a remarkable text nonetheless. It isn’t being published till May 24 but is available now for pre-order from Amazon.com. It’s hard to imagine anyone being disappointed by it.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,