Last week the government proudly announced that the nation had 105,000 designated bomb shelters, capable of holding over 86 million people.

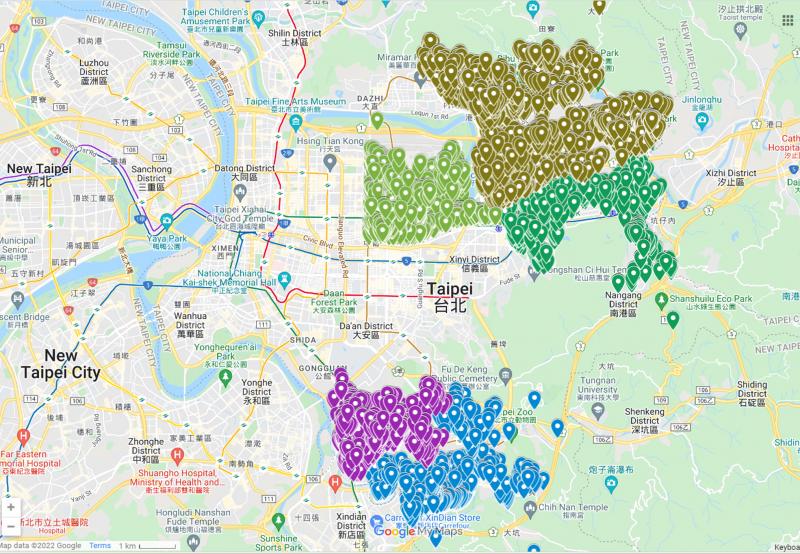

The National Police Agency has a map of the shelters on the Web (search for: 防空疏散避難專區). Apparently, at least in Taipei, some of them are indicated with signs. I checked several around my house in eastern Taichung.

The map shows that most of them are buildings that happen to have basements. The one nearest me is in a perfectly ordinary apartment building down the street. It has no markings of any kind to indicate that it is on a government list of bomb shelters. According to the government, 60 souls can cram into its basement.

Photo: Screen grab

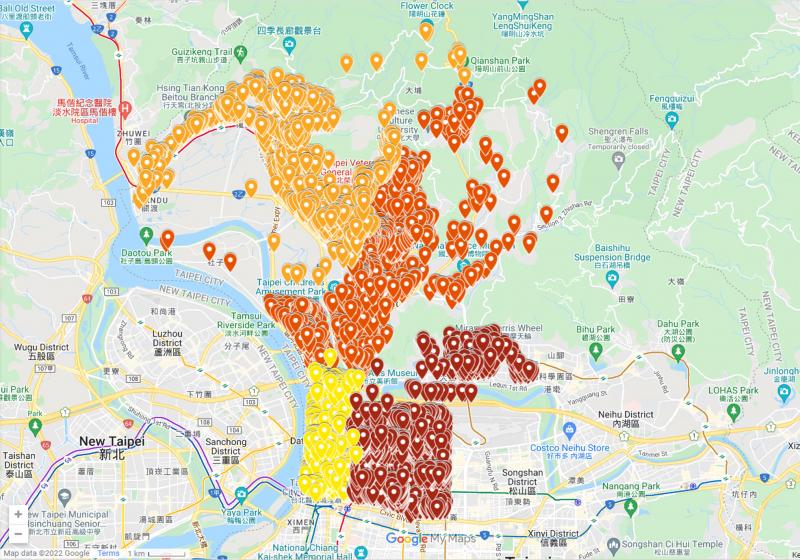

BASEMENT FOR 700 PEOPLE?

I looked at several others nearby. The map designates three buildings in a group of small homes in the next section of Dongshan Road east of my place. Those are older buildings in the “storefront” style, with a large room in front, a set of stairs and toilet in the center and a tiny kitchen area in the back. Three basements in that row of houses are supposed to hold 520, 520 and 704 people. I nearly fell over laughing when I saw that.

It seemed intuitively obvious that the numbers had been calculated using the area of the basement, by someone looking at a map and corresponding building plans, without regard to the real conditions of the buildings. Some of the buildings I looked at were down little lanes, others had only one or two small entrances, yet were supposed to accommodate hundreds of people. Anyone have a basement with toilets for 700?

Photo: Screen grab

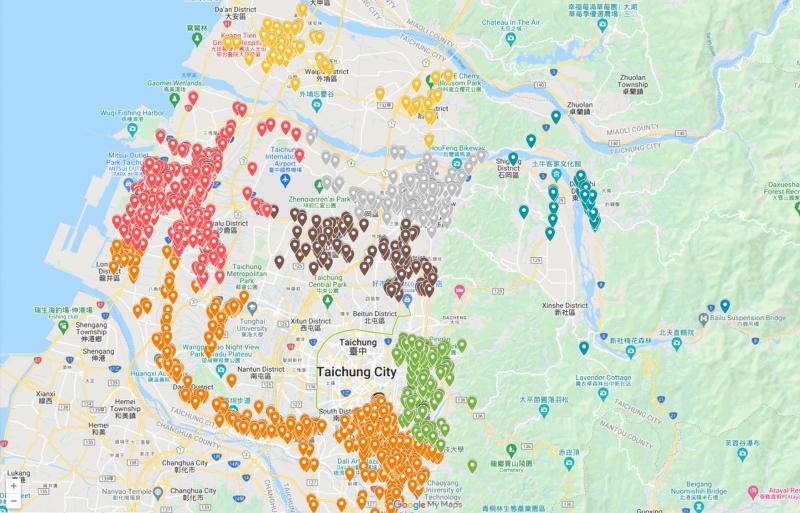

No one I talked to knew that their home or nearby homes were designated shelters. I feared, after this initial pass, that the evacuation shelter program might be a Potemkin project. I turned to a friend who had been a Taichung municipality government official and was an expert in urban planning for a better understanding of what was happening.

First, he explained, the government does not tell building owners that their basement might become an evacuation shelter because then people might demand some kind of recompense. But the emergency laws are written so that in the event of an emergency like a war, the government can requisition the building without permission for whatever it needs. Nor, under the law, does it have to inform the owner of the status of his property.

He added that this is also true of vehicles. In the old days, he said, when your vehicle got its license, it was also labeled with a number and stored in the government database in the event it needs to be requisitioned. Although the number label has since been removed from private vehicles, the law remains: in an emergency, your property is government property and can be requisitioned as needed.

Photo: Screen grab

“In wartime there will be no private property,” he said.

This applies to even to more ordinary emergencies. If the apartment building across from your house is on fire, the fire department can requisition your house as a command center for the duration of the emergency. They usually ask politely, but they do not need to.

In the event of a major disaster such as a Chinese attack, the police are responsible for coordinating evacuations. In Taichung, my friend explained, there are 625 boroughs and the borough wardens are responsible for coordinating the evacuation of the people in their neighborhoods. The disaster plans will be sent down to them, and they will direct people to designated evacuation sites.

There are 10 items on the “things to do in a disaster” list, including traffic control, neighborhood evacuations, mountain area policing, environmental protection, disaster recovery and medical care. The planning for these, required by law, is carried out by volunteers in cooperation with the National Police Agency.

The shelter sites are designated by planning units, he added, based on the local population density and similar factors.

A couple of weeks ago a Vox writer under shelling in Ukraine said that they had been told that the basements were not safe “because the walls can crack, fall down and then you’re trapped.” I asked my friend about this. He pointed out that the building codes in Taiwan require basements to be constructed to withstand earthquakes. They aren’t specifically bombproofed, though.

CIVIL DEFENSE

In Taiwan the Civil Defense program is part of the All-out Defense program, initiated under former president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) and passed in 2000. Lee first proposed the idea in 1996 in the form of “All-out Defense Consciousness,” seeking to gather the population behind the idea of resistance, as Martin Edmonds and Michael Tsai observed in their 2013 book Defending Taiwan: The Future Vision of Taiwan’s Defence Policy and Military Strategy.

The current All-out Defense Mobilization Readiness Act (全民防衛動員準備法) sets out in detail the responsibilities for each ministry and department, and specifies that the agencies requisitioning private property must send down written orders and issue receipts. It also exempts people who run their own businesses as the sole worker (interesting to see if this in practice includes freelancers and people running online shopping sites), people who have to take care of family, and individuals in ill health. Like most Taiwanese laws, it is quite reasonable.

Taiwan’s defense strategy thus includes the idea of civil defense. Yet civil defense-mindedness, it seems, has yet to percolate down to the population. The government needs to show far more leadership in this area — indeed, this seems a natural issue for the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to take up in the next election cycle, since it is unlikely that the pro-China parties will be so committed to civil defense.

Many things have changed since the old days, my friend reminded me as we chatted, since 1990, but especially since 2004. Taiwan used to be more physically ready for war, he said, but now it is more mentally ready.

“Mentally ready?” I asked.

“People see themselves as Taiwanese now. They are more mentally ready to defend Taiwan.”

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on