Feb. 21 to Feb. 27

By the end of February 2000, Taiwan’s mobile phone users had surpassed those with landlines. It was a quick surge for the industry, as just three years prior the coverage rate was 7 percent, according to the 2001 book Covering the Sky with One Hand: The Telecommunications Wars between the Four Heavenly Kings (隻手遮天: 大哥大四天王的電信大戰) by Peng Shu-fen (彭淑芬).

By the end of 2000, it was at 75 percent.

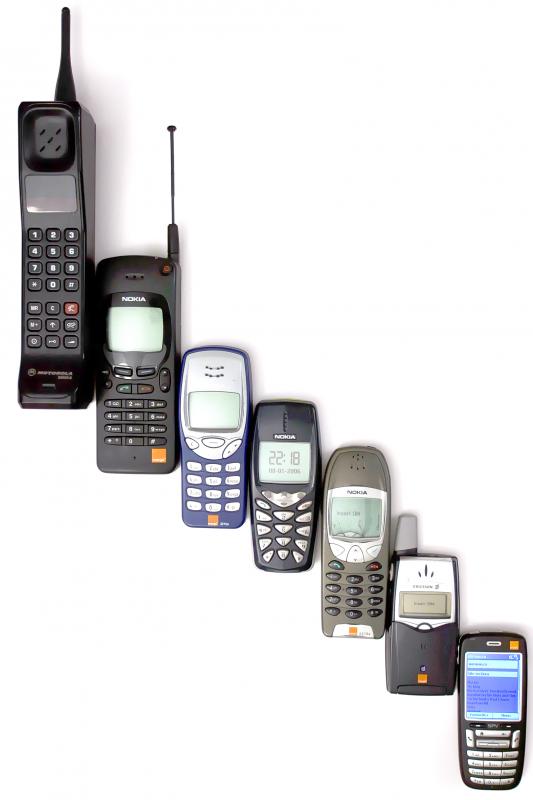

Photo: Chang Ching-ya, Taipei Times

“Although the battle for the mobile phone market was fierce, compared to other foreign markets, [Taiwan’s] developed quite rationally,” Peng writes. “Unlike Hong Kong, for example, there was no bloody price war with no regard to costs. But even though that didn’t happen here, the competition still greatly drove down phone fees.”

The trigger to these events was the government’s opening of the cell phone market to private operators in 1997. Eight participants entered the initial fray: Far EasTone Telecommunications Co (遠傳), Mobitai Communications Co (東信), Transasia Telecommunications Inc (泛亞), Chung Hwa Telecom Co (中華), KG Telecommunications Co (和信), Tung Jung Telecom (東榮) and Taiwan Mobile Co (台灣大哥大). Tung Jung was the first to fall, bought out by KG in December 1998.

By the time of the book’s writing, Taiwan’s cell phone fees fell to among the lowest in the world. The competition also drove up customer care and service quality, leading Peng to conclude that the consumers were the biggest winners of this war. Peng added that the voice-calling market was saturated, and with the advent of 2.5G Internet the next step would be moving toward data transmission.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

EXCLUSIVE COMMODITY

Before 1997, the Directorate General of Telecommunications had a monopoly over phone usage in Taiwan. Cell phones were extremely expensive — one could cost over NT$100,000. Even if you had the cash, there were long lines to obtain a phone number — the waiting list was up to about 1 million people by 1997. If you were desperate, you could buy a number off someone for as much as NT$50,000.

As an alternative, private companies tried to promote the CT2 system, a short-range mobile phone that used terrestrial base stations. People were excited and tempted by the companies’ inflated promises, paying in advance to reserve their spot and even hoping to run their own mini-operation through purchasing a costly personal base station.

This experiment ended in disappointment due to the limited range of the stations (a few hundred meters) and other technical difficulties such as the phone not working if one was moving too quickly. The users quickly returned their devices and the venture crashed.

The government finally passed the Telecommunications Act in July 1996, which aimed to open up the market to private businesses. The Directorate’s sales and business arm was separated into Chunghwa Telecom, with the goal of eventually becoming a private company (it made the transition in 2005).

The race was on. Taiwan Mobile started rolling out deals a month before the market opened, and reportedly had 15,000 customers signed up by opening day. The companies got innovative to compete against each other, offering all sorts of deals, special contracts and putting great effort into advertising.

There was still a gender balance in cell phone use at the beginning. A 1998 report by the Nielsen Corporation showed that 37 percent of men between the ages of 15 and 60 used a cell phone, while only 14 percent women did, although 20 percent expressed a desire to get one soon.

The report also found two main groups of users: those with higher incomes who wore the phone on their waist as a status symbol, and people such as salesmen who actually needed them for their jobs. It added that it would soon tap into the youth market.

Today only three of the original eight remain — Taiwan Mobile purchased Mobitai in 2004 and TransAsia in 2008, while KG was bought out by Far EasTone in 2010.

SHOWING OFF

By the end of February 2000, there were an estimated 12,180,000 cell phone users in Taiwan.

Of course, such a sudden proliferation of the technology brought problems, many of which persist today. Phone etiquette was a big issue, as discussed in the 2000 “Study on Improper Use of Cell Phones in Public Spaces (台灣公共空間內使用大哥大不當行為之探討) by Tseng Shih-yuan (曾士原).

Everyone who had one wanted to show off their new gadget, and they hung them by their waists and talked on them as much and as loud as they could, Tseng writes. It was not uncommon to see people slamming their large, seemingly indestructible phones onto the table as they arrived at a restaurant, yakking on them loudly throughout the course of the meal.

“If talking on the cell phone itself has become a fashionable leisure activity, or an action that one just can’t help showing off to the public, this means that our [already noisy] public spaces will have no chance of becoming quieter.” Tseng writes.

Before authorities clamped down on the practice, phones rang during class, in the library or at movie theaters — one interviewee said that he had heard at least 10 phones ringing during a screening.

This extreme visibility and showing off definitely hastened the popularity of mobile phones, Tseng writes.

“If someone calls you all the time, that suggests that your ability, importance and popularity are top notch,” Tseng writes. “When a cell phone becomes the symbol of how important you are, then even those who don’t actually need cell phones would be eager to have one too.”

Two decades later, this behavior has waned significantly, though it still persists.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand