The suicides might have seemed apocryphal, but the ritual meant to banish their malevolent ghosts was real. And that had the residents of Taoyuan’s Jhongli District (中壢) concerned for their safety.

According to reports in March last year in Mirror Media and Storm Media, four people had taken their lives by burning coal in the alcove of a townhouse they were renting near Lane 270 on Jhongshan Street (中山). After the father of the family learned of the tragedy, he hung himself. The landlord later rented out the space, but tenants kept committing suicide by hanging. Convinced that evil spirits were killing his tenants, the landlord hired religious specialists to perform a songrouzong (送肉粽, lit: “delivering meat dumplings”), a folk ritual thought to banish demons and ghosts.

Hsu Bai-lung (許柏龍), a ritual master and demon-banishing specialist, tells Eastern Broadcasting that the souls of those who commit suicide “hang around the visible world seeking revenge” on the living. And the greater the number of deaths, the more malicious the spirits.

Photo courtesy of Wowing Entertainment

Hsu’s task, like any demon banisher, is to employ the songrouzong ritual to remove these evil doers from the home where the suicide has taken place and banish them to the sea so they will no longer haunt the living.

And judging by how often the ritual is performed, it seems to be an effective practice. And yet, the ritual on Jhongshan Street never took place.

Though it runs on a spectrum, the majority of Taiwanese believe in the existence of malevolent ghosts. The more brutal the death, the greater potential there is for harm. And the ghosts resulting from a suicide are believed to be among the most lethal. Homes where a suicide takes place, for example, plummet in value. The belief in ghosts is so strong, in fact, there is an entire month — ghost month — devoted to appeasing these wandering mischief makers.

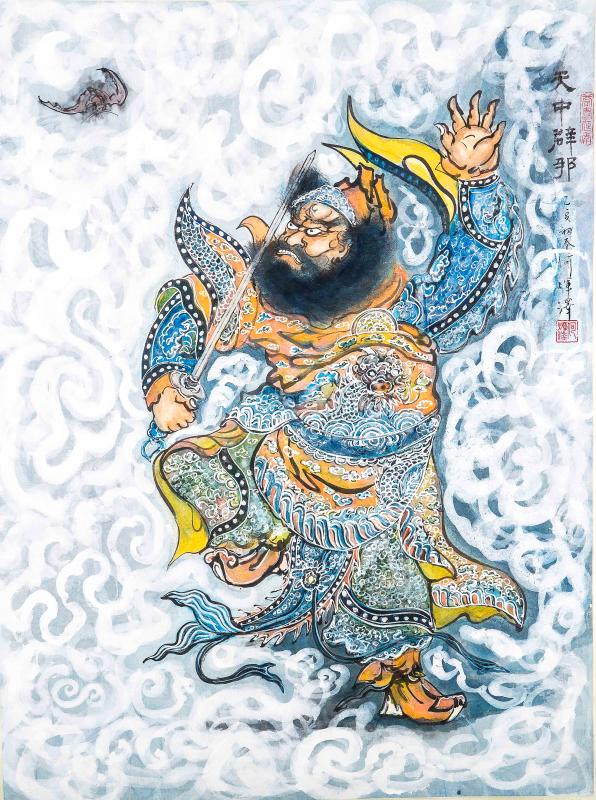

Illustration: Courtesty of Ho Hui-tse

DELICACIES AND DEMONS

Folklorist Yang Teng-ke (楊登嵙) says songrouzong has existed in Taiwan for four centuries and is centered mainly around the old trading center of Lugang Township (鹿港) in Changhua County. Yang says that what makes the ritual unique is that it is specifically held for a person who has committed suicide by hanging.

The term zongzi (粽子) refers to a delicacy of glutinous rice and pork wrapped in bamboo leaves and bound and hung with string and sold in night markets. By analogy, the hanged individual takes on the appearance of the hanging zongzi.

Photo: CNA

And this isn’t the kind of zongzi one brings home to become part of a family feast during the Lunar New Year. Instead, the evil that it represents is “delivered” (song, 送) by procession away from the home where the suicide took place, a process that begins either at 8pm or 10pm at night, and generally requires two hours to complete.

Ritual specialists choose these times because that is when banishing the ghosts is most effective.

Additionally, the phrase “tying the dumplings” in Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) sounds similar to the phrase “hang oneself.” The phrase is employed as a euphemism by ritual specialists so that they don’t directly say the word suicide and therefore attract the attention of the malevolent spirits.

Photo courtesy of Yang Sheng-hua

‘DO NOT PANIC’

Because evil spirits are resentful and dangerous, banishing them is a difficult and complicated task. It begins with organizers posting a notice in the neighborhood and on social media warning residents to avoid the procession, which makes songrouzong somewhat of a paradox.

Typically, crowds gather to participate in or watch a procession. They are spectacles to behold, and temple committees spend generously on firecrackers and music, performance troupes and entranced spirit mediums. Processions are celebratory, a chance for gods to protect a ritual space and pass on fortune and good health to the living.

Photo: Liu Hsiao-hsin, Taipei Times

The songrouzong procession is pretty much the opposite. There are still firecrackers and banging drums, spirit mediums and performance troupes dressed as deities. But organizers implore residents to stay away for fear that they will be impacted by the malicious spirit that is being removed. In other words, anything but celebratory.

Judging by the dozen songrouzong notices reviewed by the Taipei Times, they follow a pretty standard format. A notice from Taichung in March last year, for example, states the ritual’s name, the date, the time the procession will take place and an admonition: “Unless absolutely necessary, please stay in your homes during this time so as to avoid any offences.”

They typically sign off with: “Do not panic” (請勿驚慌).

A notice from Taichung’s Shengkeng District (神岡) in March 2020 tells people what to do if they accidentally stumble onto the procession: Turn your head away and invoke the Amitabha Buddha (阿彌陀佛) under your breath. After it has passed, go to a temple and request a “purification talisman” (淨符).

Dizziness and nausea, coma and even death can result if a person accidentally stumbles onto the procession and doesn’t take proper precautions after they do.

ZHONG KUI BANISHES EVIL

The appointed day finds ritual masters going to a temple to invoke Zhong Kui (鍾馗), a deity known for his prowess in banishing demons, ghosts and other evil spirits. A songrouzong troupe (送肉粽的隊伍) place talismans that obstruct malevolent forces along the procession route.

Towards evening, ritual specialist dresses as an avatar of Zhong Kui and takes on his spiritual powers.

Zhong Kui travels to the home where the suicide has taken place and gathers objects handled by the hanged individual.

The most potent object is the rope. Folklorist Yang says that ideally the original rope should be used in the ritual because it possesses the strongest supernatural power and has the greatest potential to be dangerous to the living.

“At first, the police will take the rope for its investigation,” Yang says. “But after it concludes, the rope must be dealt with. If it’s left at the police station or evidence lockup, its malevolent energy (陰氣) will become strong.”

If the rope cannot be procured, one can use a substitute symbolizing malignant forces. These items are then brought out to an large iron box with wheels and paraded through the streets. As they do so, they fill the box with all the ritual objects — talismans, clothing, rope — and push it to the coast, where the ritual ends with a massive conflagration.

Zhong Kui stands in front of the burning pyre and says: “Waters take these grievances, once absorbed into the ocean, never to return.” (千冤萬怨隨水去, 一化大海不回來)

NOT IN MY NEIGHBORHOOD

Demons, noise and air pollution, a dictate to stay indoors — who wouldn’t want a songrouzong ritual passing through their neighborhood? And between eight and 10pm or 10pm and midnight. Well, it turns out that many don’t.

Lugang is a small village located by the seaside with a centuries-long songrouzong tradition, so it isn’t that much of a disruption to locals.

That hasn’t been the case when it’s been held elsewhere. Jhongli District isn’t that close to the ocean, which means the procession route can be a few kilometers long, passing several neighborhoods.

Another ritual that was to be held in October last year, was to pass the Taiwan High Speed Rail Corp’s (THSR) Taoyuan Station, a densely populated area with office buildings, clothing outlets, coffee shops and several eateries. Imploring people to stay indoors starting from 8pm didn’t sit well with locals.

Hsu, the demon busting specialist, says that “people are afraid of the ritual because they don’t know what it’s for. And because they are afraid of it, they are against it.”

Yet, it seems more accurate to say that the public does understand it, and that’s why they don’t want it in their neighborhood because it draws their attention to something they want to avoid: the pollution of death. Every notice beseeches residents to be vigilant of the procession: Look away from it, go to the temple and acquire talismans to mitigate against it. Invoking the Amitabha Buddha might be a temporary balm, but the lingering taint of death always remains. To a certain extent, the ritual has been a victim of its own success.

There has developed in Taiwan over the past few years the general belief that folk rituals shouldn’t interfere with people’s lives. Temples have sealed incense burners to reduce air pollution and discourage the use of ritual offerings as wasteful. Gone are the days when large-scale pilgrimages fail to clean up the tons of spent firecrackers along the procession route. Today, temples, like any other organization wanting to use public space, have to apply for permits. Failure to do so will result in fines, as happened with a Bombing Han Dan ritual in New Taipei City.

After the organizers of the Jhongli and Taoyuan rituals posted a notice on social media, residents immediately wanted to know if they had applied for the proper permits. They hadn’t. And so they were postponed.

As of press time they haven’t been rescheduled.

Under pressure, President William Lai (賴清德) has enacted his first cabinet reshuffle. Whether it will be enough to staunch the bleeding remains to be seen. Cabinet members in the Executive Yuan almost always end up as sacrificial lambs, especially those appointed early in a president’s term. When presidents are under pressure, the cabinet is reshuffled. This is not unique to any party or president; this is the custom. This is the case in many democracies, especially parliamentary ones. In Taiwan, constitutionally the president presides over the heads of the five branches of government, each of which is confusingly translated as “president”

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and

The Venice Film Festival kicked off with the world premiere of Paolo Sorrentino’s La Grazia Wednesday night on the Lido. The opening ceremony of the festival also saw Francis Ford Coppola presenting filmmaker Werner Herzog with a lifetime achievement prize. The 82nd edition of the glamorous international film festival is playing host to many Hollywood stars, including George Clooney, Julia Roberts and Dwayne Johnson, and famed auteurs, from Guillermo del Toro to Kathryn Bigelow, who all have films debuting over the next 10 days. The conflict in Gaza has also already been an everpresent topic both outside the festival’s walls, where

The low voter turnout for the referendum on Aug. 23 shows that many Taiwanese are apathetic about nuclear energy, but there are long-term energy stakes involved that the public needs to grasp Taiwan faces an energy trilemma: soaring AI-driven demand, pressure to cut carbon and reliance on fragile fuel imports. But the nuclear referendum on Aug. 23 showed how little this registered with voters, many of whom neither see the long game nor grasp the stakes. Volunteer referendum worker Vivian Chen (陳薇安) put it bluntly: “I’ve seen many people asking what they’re voting for when they arrive to vote. They cast their vote without even doing any research.” Imagine Taiwanese voters invited to a poker table. The bet looked simple — yes or no — yet most never showed. More than two-thirds of those