The theory of general relativity holds that a massive body like Earth curves space-time, causing time to slow as you approach the object — so a person on top of a mountain ages a tiny bit faster than someone at sea level.

US scientists have now confirmed the theory at the smallest scale ever, demonstrating that clocks tick at different rates when separated by fractions of a millimeter.

Jun Ye, of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado Boulder, said their new clock was “by far” the most precise ever built — and could pave the way for new discoveries in quantum mechanics, the rulebook for the subatomic world.

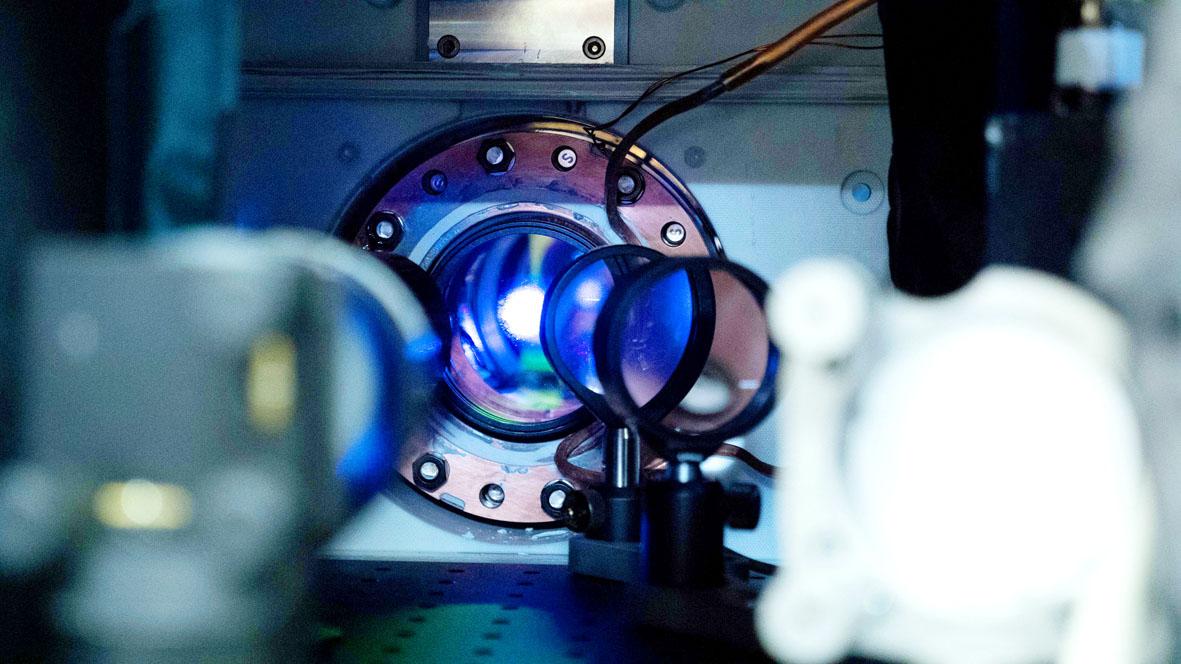

Photo: AFP

Ye and colleagues published their findings Wednesday in the prestigious journal Nature, describing the engineering advances that enabled them to build a device 50 times more precise than today’s best atomic clocks.

It wasn’t until the invention of atomic clocks — which keep time by detecting the transition between two energy states inside an atom exposed to a particular frequency — that scientists could prove Albert Einstein’s 1915 theory.

Early experiments included the Gravity Probe A of 1976, which involved a spacecraft 10,000 kilometers above Earth’s surface and showed that an onboard clock was faster than an equivalent on Earth by one second every 73 years.

Since then, clocks have become more and more precise, and thus better able to detect the effects of relativity.

In 2010, NIST scientists observed time moving at different rates when their clock was moved 33 centimeters higher.

THEORY OF EVERYTHING

Ye’s key breakthrough was working with webs of light, known as optical lattices, to trap atoms in orderly arrangements. This is to stop the atoms from falling due to gravity or otherwise moving, resulting in a loss of accuracy.

Inside Ye’s new clock are 100,000 strontium atoms, layered on top of each other like a stack of pancakes, in total about a millimeter high.

The clock is so precise that when the scientists divided the stack into two, they could detect differences in time in the top and bottom halves.

At this level of accuracy, clocks essentially act as sensors.

“Space and time are connected,” said Ye. “And with time measurement so precise, you can actually see how space is changing in real time — Earth is a lively, living body.”

Such clocks spread out over a volcanically-active region could tell geologists the difference between solid rock and lava, helping predict eruptions. Or, for example, study how global warming is causing glaciers to melt and oceans to rise.

What excites Ye most, however, is how future clocks could usher in a completely new realm of physics. The current clock can detect time differences across 200 microns — but if that was brought down to 20 microns, it could start to probe the quantum world, helping bridge disparities in theory.

While relativity beautifully explains how large objects like planets and galaxies behave, it is famously incompatible with quantum mechanics, which deals with the very small.

According to quantum theory, every particle is also a wave — and can occupy multiple places at the same time, something known as superposition. But it’s not clear how an object in two places at once would distort space-time, per Einstein’s theory.

The intersection of the two fields therefore would bring physics a step closer to a unifying “theory of everything” that explains all physical phenomena of the cosmos.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

What does the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) in the Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) era stand for? What sets it apart from their allies, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)? With some shifts in tone and emphasis, the KMT’s stances have not changed significantly since the late 2000s and the era of former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). The Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) current platform formed in the mid-2010s under the guidance of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and current President William Lai (賴清德) campaigned on continuity. Though their ideological stances may be a bit stale, they have the advantage of being broadly understood by the voters.