Feeling adventurous on Monday afternoon, Emie Lomba opened a ready-to-eat packet of spicy Korean seasoned perilla leaves. She balked at the aftertaste. Feeling bad about just throwing it away, she posted a photo of it on the Buy Nothing Taipei Facebook Group, fully disclosing its condition. She found a taker in just over an hour.

“I figured other people would be interested in trying it,” Lomba says, adding that it was her first time donating open food. “I was quite hesitant at first, but I saw some people had donated food they’d either made on their own, or leftovers from a restaurant. I was expecting a quick response because this community is very responsive.”

Launched in June 2020, Buy Nothing Taipei is one of numerous free stuff Facebook groups in Taiwan — but it is one of the few that are in English or are English-friendly. It’s quite active for its size of about 4,500 members, who made 573 posts in the past month as of yesterday.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

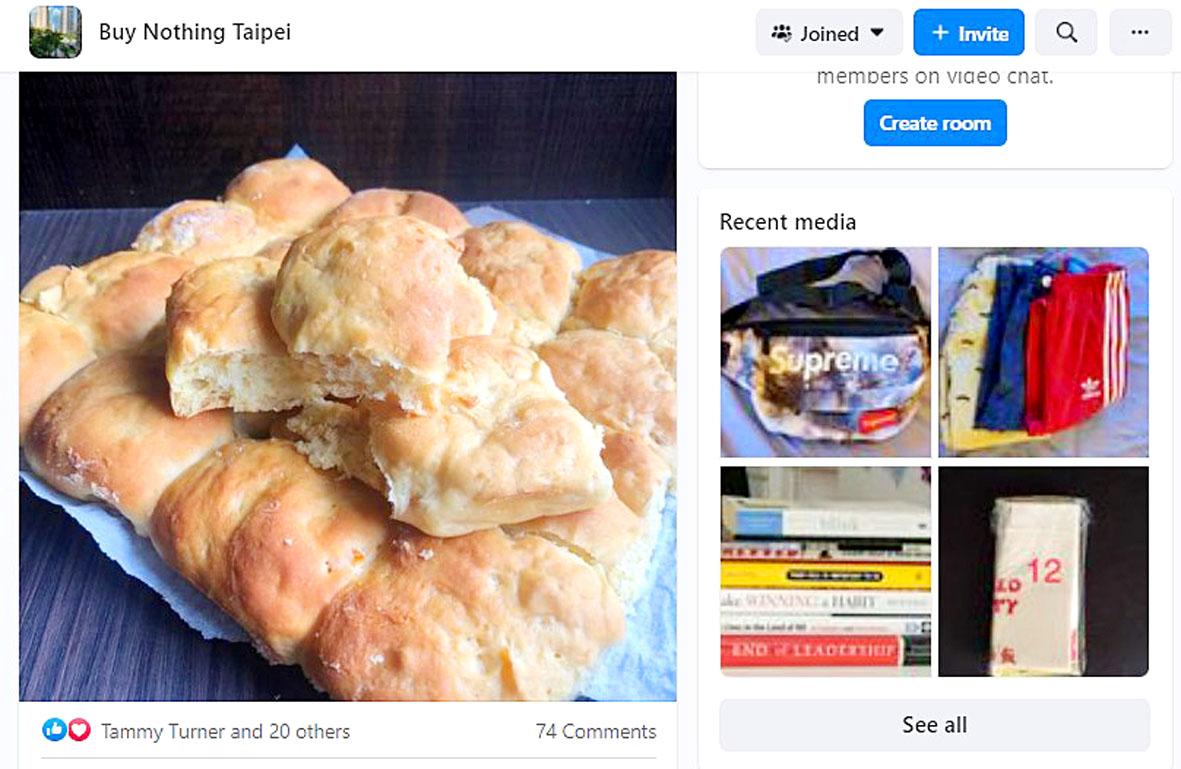

In addition to posts in search of or giving away the usual items such as clothes, tools and furniture, there are also intriguing endeavors such as a baking enthusiast regularly giving away extra goods after trying a new recipe. Her latest offering is a sourdough dinner roll with kumquat marmalade and candied oranges.

“I’ve heard some amazing stories,” group founder Mei Lin (林巧媚) says, including one time when someone provided a truckload of costumes and makeup for a family needing them for a 60th birthday party. Someone even gave away a car once, she adds.

SOCIAL ASPECT?

At first glance, these groups seem to focus more on reducing waste and consumption and less on the intentional social aspect touted by the Buy Nothing Project founders (“A banana, concrete — those are good gifts:’ the recycling group turning strangers into friends,” Jan. 16, Taipei Times). Users are, for instance, not encouraged to share why they need the item or what it means to them, for example — the Chinese-language Buy Nothing Project Taiwan group even specifically states “you don’t have to tell a story.”

Despite this, both Lin and Lomba refer to Buy Nothing Taipei as a warm, generous and like-minded “community,” where the satisfaction goes beyond exchanging items and saving the environment.

“I’ve been gifted a lot of things that have made me smile, and I hope that what I’ve gifted to others makes them feel the same way … Most of us are so thankful toward others for helping us repurpose or reuse things that we don’t use anymore — especially since recycling and trash removal in Taiwan is a bit of a hassle. It’s always nice to have a more purposeful outlet for getting things that we don’t need out of our lives.”

Photo courtesy of Emie Lomba

Despite regional differences, the Buy Nothing groups generally abide by one credo: the giver has the right to choose the recipient.

“In my opinion it shouldn’t be whoever gets to it first,” Lin says. “Someone could be monitoring the posts all the time.”

Lin uses a random number generator when she gives away items, but people can also look at the profiles of the respondents and make their own conclusions.

Heyling Chien (簡毓玲), founder of Free Your Stuff Taipei, notes that disputes have greatly decreased after she installed the rule in 2018, as the giver becomes solely responsible for deciding to whom the item goes.

GAINING TRACTION

Chien’s bilingual group is one of the earlier ones for English users, launched in 2014 after she returned home from Berlin. The group is modeled after Free Your Stuff Berlin, which today has more than 187,000 members. Free Your Stuff Taipei has 5,300 members.

“Back then, there were only groups for trading stuff,” Chien says. “And there weren’t a lot of members.”

She started the group initially to declutter her family home in Keelung, but it didn’t take off there so she shifted it to Taipei. Most initial members were her friends.

Lin started her group after seeing the garbage area of her Xinyi apartment building piled up with designer shoes and bags. Lin calls herself an environmentalist: she doesn’t use plastic bags, she composts, her children wear second-hand clothing and so on.

The page took off from there with the help of a number of moderators. Lin is glad that items have often been returned to the community after the user didn’t need them anymore — such as baby strollers.

Sometimes people question the hygiene of the items, such as when people give away used food or dirty litter boxes. Lin says that’s up to the person taking the items, as some people may be in a hurry or just don’t have time to clean their items.

“If you want it, you wash it,” she says.

Chien requires people to post the expiration date of food they’re giving out. However, if someone believes that it can be eaten past the date, they can still take it.

So far, there are just a few items (besides the obvious guns and drugs) that are banned on Free Your Stuff Taipei: animals and illegal electronic items like pirated software and movies.

The buy nothing concept has gained traction in Taiwan over the past decade or so, and in addition to the Facebook groups there are also free markets (免廢市集) that emphasize waste reduction and the joy of giving rather than framing it as a charity event helping the needy.

“If you have a use for it, it doesn’t matter how wealthy you are, just take it,” event organizers stated before last November’s nationwide Free Market Day. “What the Free Market really wants to help are these resources that are no longer cherished.”

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

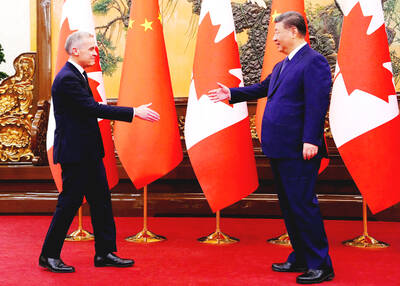

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director