Few historical revisionists can have been as audacious as Grace C. Huang in comparing Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) to Mahatma Gandhi. Yet, not only does Huang attempt the parallel, she makes rather a good case for it.

Previous studies of leadership, Huang writes, have “tended to portray Gandhi as moral, visionary leader and Chiang as a problematic, power hungry one.” While Gandhi’s leadership was “transformative,” Chiang was — at best — a victim of circumstance. More recent scholarship, Huang notes, has attempted to rehabilitate Chiang while highlighting the unsavory aspects of Gandhi’s character.

Rather than any personality trait, though, Huang examines an element of the national identity narratives the leaders attempted to foster, namely the reliance on the motif of shame. In Gandhi’s case, the shame came quite obviously from the British. Huang cites a well-known tale of an assault by a coachman in South Africa as the catalyst for Gandhi’s “journey of ‘avenging’ his personal and the Indian collective humiliation.”

For Chiang, the British also played a role by initiating the “century of humiliation” in the First Opium War. However, it was Japan’s treatment of China, at the tail-end of the “century” that was crucial in forming Chiang’s shame-based philosophy.

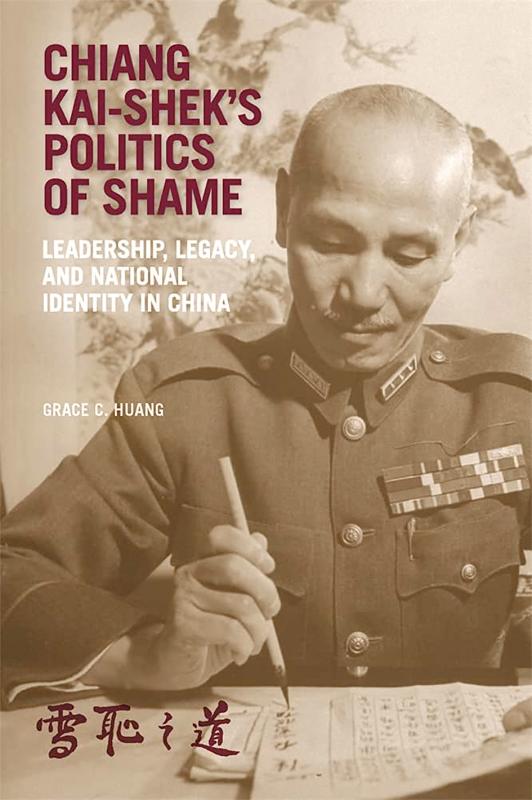

Based on Huang’s examination of Shilue Gaoben (事略稿本) — a huge archive of Chiang’s diaries, speeches, and telegrams held at Taipei’s Academia Historica — the Jinan Incident of 1928 of the Mukden Incident of 1931 are cited as the catalysts for his use of the Confucian notion of chi (恥, shame or humiliation) as a tactic for unifying China around his leadership. While it was an impetus for the development of his philosophy of satyagraha, translated here as “truth struggle,” Gandhi’s shame as a victim was transposed onto the perpetrators of the injustice. By seeking to engage the oppressor’s conscience, “he provided an alternative to a dominant Western conception of courage by relying on moral sensibilities and a capacity for guilt.”

Like Gandhi, Chiang extended his sense of personal shame to the indignities experienced by his compatriots; yet — in contrast to the Indian leader — Chiang did not attempt to prick the aggressors’ conscience. Realizing he was not yet able to oppose such a powerful foe, he acquiesced to Japanese demands, even when that meant him taking a hit in terms of public perception.

SHOULDERING THE BURDEN

In this regard, Chiang casts himself as a Christ-like figure — a parallel Huang raises later in the text when discussing Chiang’s incorporation of Western ideas into his philosophy of chi. Although, he had not yet converted to Christianity, an entry from May 15, 1928, shortly after his capitulation at Jinan, makes the comparison obvious.

Wang Yu-gao (王宇高), an undersecretary, and one of Shilue Gaoben’s compilers, quotes Chiang as stoical about Japanese demands for an apology over the standoff, which started with the occupation of Chinese territory and ended with 3,000 Chinese dead.

“If the Japanese still require that the Chinese commander-in-chief must apologize to Japan, this humiliation, I can personally take,” Chiang is quoted as saying. “But the humiliation to the country, how can I forget?” However, Chiang’s professions of willingness to assume responsibility are negated by the revelation that he fired then-foreign minister Huang Fu (黃郛), who had been tasked with conveying the apology. In this way, the author concedes, Chiang could “let his subordinate take the fall — after all, the record would show, it was Huang’s idea to have Chiang personally apologize.”

Still, the author argues, rather unconvincingly, such maneuvers can be seen as “in the service of the larger mission of uniting China.”

PRIVATE MUSINGS TO PUBLIC POLICY

If the claim that Chiang was forced to endure humiliation is fair, the wider argument that he employed chi to leave his imprint on his subjects is far less tenable. Nowhere is concrete evidence of any normative impact of Chiang’s philosophy provided.

The fulcrum of Grace C. Huang’s argument is that previous analyses have worked backward from the conclusion (that Chiang failed) to the premisses (that he was a poor leader.) But arguments about Chiang’s incompetence need not resort to such question begging. More importantly, proof to the contrary needs to be provided. How, if at all, were Chiang’s musings on national humiliation conveyed to the public, not to mention formed into coherent policymaking?

Aside from the accounts of the protracted (and often scarcely comprehensible) harangues the Generalissimo subjected audiences to, the closest we get to an answer is the claim that his New Life Movement (新生活運動) bridged the gap. Even here, Huang offers little to show that the often-arbitrary pronouncements of the movement had anything more than a superficial effect.

NEGLIGIBLE LEGACY

Finally, the tenuousness of the tie-in with Taiwan is disappointing. In her introduction, Huang draws in her family history, noting her “bewilderment” that a grandfather who had fled Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) persecution during the White Terror could “give time, money, and enthusiastic praise to Chiang Kai-shek’s party” during the 2000 election. Her confusion, she says, motivated her attempt to unravel the enigma of Chiang’s leadership.

This conundrum is never broached. Instead, we are left with a short passage about Chiang’s legacy in Taiwan, which Huang admits is negligible. No attempt is made to argue that Chiang’s personality, rather than the KMT’s ill-gotten resources and decades-long control of the media, influenced its enduring popularity in the post-Martial Law era. And for obvious reasons: there’s none to be made — even less so for any continued impact Chiang’s arcane morality might have. This contrasts with the plausible case Huang makes for Chiang’s role in the ongoing narrative of humiliation in China.

“Nonetheless,” Huang asserts, “Chiang’s efforts to avenge the new humiliation of having lost the mainland instituted important reforms that set Taiwan on the path of modern economic and democratic development.”

The real shame here is that an engaging and original piece of scholarship is undermined by such arguments.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the

Six weeks before I embarked on a research mission in Kyoto, I was sitting alone at a bar counter in Melbourne. Next to me, a woman was bragging loudly to a friend: She, too, was heading to Kyoto, I quickly discerned. Except her trip was in four months. And she’d just pulled an all-nighter booking restaurant reservations. As I snooped on the conversation, I broke out in a sweat, panicking because I’d yet to secure a single table. Then I remembered: Eating well in Japan is absolutely not something to lose sleep over. It’s true that the best-known institutions book up faster

Though the total area of Penghu isn’t that large, exploring all of it — including its numerous outlying islands — could easily take a couple of weeks. The most remote township accessible by road from Magong City (馬公市) is Siyu (西嶼鄉), and this place alone deserves at least two days to fully appreciate. Whether it’s beaches, architecture, museums, snacks, sunrises or sunsets that attract you, Siyu has something for everyone. Though only 5km from Magong by sea, no ferry service currently exists and it must be reached by a long circuitous route around the main island of Penghu, with the