After the third tour bus arrives, depositing its 50 or so test-takers at the driving school’s track in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店), I’ve had enough. I’ve been sitting under the sun for the previous hour waiting to be assigned a place so I can complete the last two parts of my driving test: the track test and road test. But I haven’t yet been assigned a place because the document required to register is on another bus — the one that just arrived.

Dozens of students are already crowded out front of a tiny office at the entrance to the driving course when I step off the first tour bus at 9:30am. Judging by their listless expressions, they’ve been there since I’d started the written test two hours earlier. The first and more numerous group, waiting to take the track test, are lined up on stools, many protected from the sun under an awning; the other, road test group were huddled under the portico of a house 20 meters away. A couple on a stool in front of me are hunched over a mobile phone, occasionally looking up to see if their line is moving. It isn’t.

THE INSTRUCTOR, THE COURSE

Photo: Wang Chun-chung, Taipei Times

I’ve been wanting to get my license for years. Although I had an international license when I first arrived in Taiwan, I didn’t transfer it over to a local one and it soon expired. The most seamless way to get a driver’s license — and the way almost all Taiwanese do — is to enroll in a cram school. So, NT$12,000 in hand, I made my way to a Top One Driving School (第一汽車駕駛人訓練班) office in Gongguan and signed up for the five-week course.

Confident of my Chinese-language ability, I skipped the chance to do it in English. Turn right, turn left. Back up, move forward. Reverse here, park there. How hard could it be? Besides, the road rule booklet for the written test is in English, one of 10 languages that the official test can be taken in. Well, it turns out that language comprehension also depends on the attitude of the person who is speaking.

My driving instructor arrived with a scowl, a purple umbrella and dressed in street clothes, unlike all the other instructors, who were dressed in uniform. Over the course of the next few weeks, he didn’t so much speak as mumble, using as few words as possible, though usually none at all. My questions were met with silence, comments evoked audible sighs. While practicing backing up, he’d yank the wheel if I didn’t rotate it enough — or too much.

Photo: Wang Chun-chung, Taipei Times

Because I have considerable driving experience, the instructor didn’t have to be in the car very often, affording him time to sit at the side of the track, often under the purple umbrella, smoking a cigarette.

That purple umbrella. If the sun was out, which it usually was, so was the umbrella. On one sunny day, he jumped into another student’s car, rolled down the window and opened the umbrella — effectively blocking the driver’s view of the right-hand mirror — while the student drove around the track.

Then again, this probably didn’t matter because all practice vehicles are marked in such a way that students don’t have to pay close attention to the road.

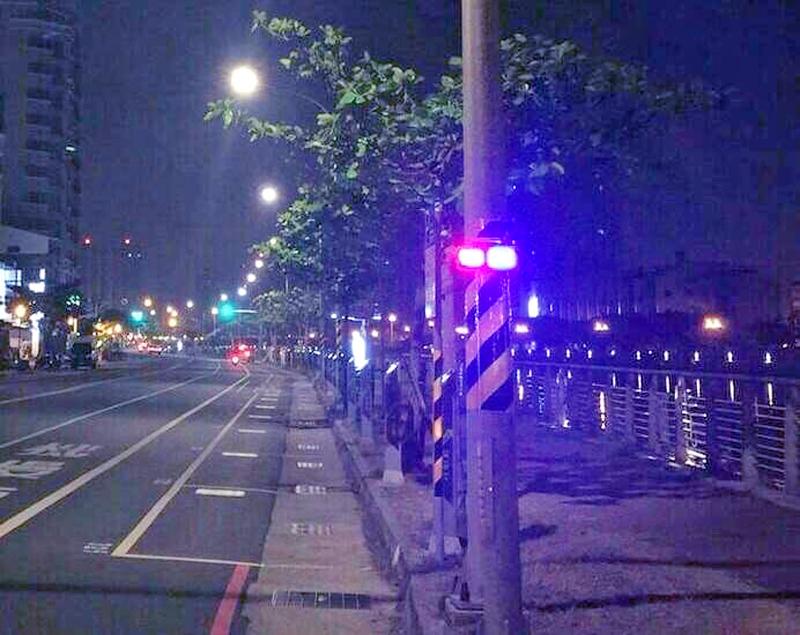

Photo: Wang Chun-chung, Taipei Times

Take backing up into a parking space, for example. One only has to back the vehicle up to a point where a paper clip, conveniently jammed into the trim above the rear passenger window, lines up with a yellow post at the side of the road. Once lined up, fully rotate the steering wheel and back in. Piece of cake.

The first time I did this I had no idea that the paper clip was there, and as a consequence, I kept getting docked points. Amid audible sighs of annoyance, my instructor eventually poked my shoulder and pointed to the paper clip and the yellow post.

The parallel parking component followed a similar rule book. But instead of a paper clip as marker, the grab handle above the front passenger seat had to line up with another yellow post. And so on. In short, the cram school provided a kind of cheat sheet for students. But what happens, I was thinking, when we have to do the actual test? Will I still be able to do this without a paper clip? Of course, I would later learn that the practice and testing courses were one and the same — paper clip and all.

In the meantime, I had bigger problems to deal with. The instructor became, over the first three lessons, increasingly insolent, even hostile, and incommunicable. And it wasn’t just with me. I noticed that he took this attitude with other students as well.

I’d been complaining about my instructor’s shitty attitude to anyone who would listen. Nobody was sympathetic because everyone has already gone through the same process and experienced, to a greater or lesser degree, the same kind of driving instructor.

Still, I couldn’t bear another lesson with him.

Impossible, I was told when I requested a change of instructor. But, I insisted, I can’t understand what he’s saying — something that might be needed if I’m driving on a city street.

The director of the driving track, who I knew could speak English because that was the language he was using to teach foreign student, who looked and sounded like he was from southeast Asia, said changing instructors was impossible. If there are any serious problems, he added, I could talk to him, thinking to myself that the problem is serious enough for me to be talking to him right now.

So no substitute was made.

THE TEST

On a clear Friday morning, the packed tour bus left at 6:30am, arriving 40 minutes later at a branch of the Taipei Motor Vehicle Office in Shilin District (士林) . There were already about 50 test-takers lingering outside of the shuttered building. Fifteen minutes later, a woman appeared and, our medical exam record in hand, called out our names one-by-one. The roll-call complete, we are separated into three groups and brought into the building.

The written test took 10 minutes to complete and, once assigned a passing grade, I boarded another tour bus and waited 20 minutes before departing for the aforementioned track in Sindian, 45 minutes away. And so, after arriving, I’m ushered to the side and told to wait until a bus arrives with my medical record, which also serves as my registration ID.

When the third bus arrived, I’d had enough. Insolent instructor, late shuttle buses and continuous waiting. To top everything off, when the other foreigner gets off the third bus, he’s immediately pulled aside by the director and placed in line. Five minutes later he starts the track test, while I’ve already waited close to 90 minutes.

Annoyed, I go over and tell the director that I’ve got to work at noon, preparing to get into a confrontation if I’m forced to wait another 90 or more minutes.

“You’re next,” the director says. And so, 10 minutes later, I’m driving around the track (deduct 16 points for failing the back up parking space) and completing the road test (no errors). I finish by 11:15am and, after filling out some paperwork, I am told to pick up my license two weeks later in Gongguan. As I leave, the couple with the mobile phone are sitting on the same stools, giving me the stink eye for what they justifiably think is a foreigner jumping the line.

In retrospect, I kept thinking that the entire five-week course was a fiasco — it certainly didn’t teach me to drive safely. But a friend later told me that I was missing the point: learning to drive isn’t why you sign up for the cram school. The point is to pass the driver’s test. Learning to drive is something that can be done down the road.

THE FINAL F-CK YOU

Two weeks later, and I’m not surprised that my passport name is nowhere to be found on the license, which I explicitly told the company to add when I signed on to the course.

“The competent authority says the name has to be in Chinese,” I’m told.

I understand that, I reply, but you are the person who I told to use my given and Chinese names. Why can’t there be both?

That fizzled her wires. She then takes out a piece of paper and tells me to photograph the contact information for the Taipei City Motor Vehicles Office.

“Just contact them and get them to deal with it,” she says.

As I’m walking out of the office, the woman calls from behind me: “Be sure to give us five stars.”

Seven hundred job applications. One interview. Marco Mascaro arrived in Taiwan last year with a PhD in engineering physics and years of experience at a European research center. He thought his Gold Card would guarantee him a foothold in Taiwan’s job market. “It’s marketed as if Taiwan really needs you,” the 33-year-old Italian says. “The reality is that companies here don’t really need us.” The Employment Gold Card was designed to fix Taiwan’s labor shortage by offering foreign professionals a combined resident visa and open work permit valid for three years. But for many, like Mascaro, the welcome mat ends at the door. A

Last week gave us the droll little comedy of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) consul general in Osaka posting a threat on X in response to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi saying to the Diet that a Chinese attack on Taiwan may be an “existential threat” to Japan. That would allow Japanese Self Defence Forces to respond militarily. The PRC representative then said that if a “filthy neck sticks itself in uninvited, we will cut it off without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared for that?” This was widely, and probably deliberately, construed as a threat to behead Takaichi, though it

If China attacks, will Taiwanese be willing to fight? Analysts of certain types obsess over questions like this, especially military analysts and those with an ax to grind as to whether Taiwan is worth defending, or should be cut loose to appease Beijing. Fellow columnist Michael Turton in “Notes from Central Taiwan: Willing to fight for the homeland” (Nov. 6, page 12) provides a superb analysis of this topic, how it is used and manipulated to political ends and what the underlying data shows. The problem is that most analysis is centered around polling data, which as Turton observes, “many of these

Since Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) was elected Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair on Oct. 18, she has become a polarizing figure. Her supporters see her as a firebrand critic of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), while others, including some in her own party, have charged that she is Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) preferred candidate and that her election was possibly supported by the Chinese Communist Party’s (CPP) unit for political warfare and international influence, the “united front.” Indeed, Xi quickly congratulated Cheng upon her election. The 55-year-old former lawmaker and ex-talk show host, who was sworn in on Nov.