For Taiwanese in an earlier time, most of family life revolved around parents and veneration for previous generations who had passed on to their descendants the source of sustenance — land. You could see the lush green rice fields terraced up the hills, or golden with stalks bending under the grains heavy before harvest. I knew that daughters-in-law regularly placed bowls of rice and meat on family altars on which were tablets with names of the ancestors.

When I was 18, in 1967, a handsome young man invited me to go with his family by car to their ancestral farm in New Taipei City’s Sansia District (三峽). His grandmother, a tiny woman with bound feet, quickly changed into a snow-white blouse. She signaled for us to kneel before the family altar holding incense sticks. I did not understand until later that we had thus pledged to continue the family line.

HISTORICAL MEMORY

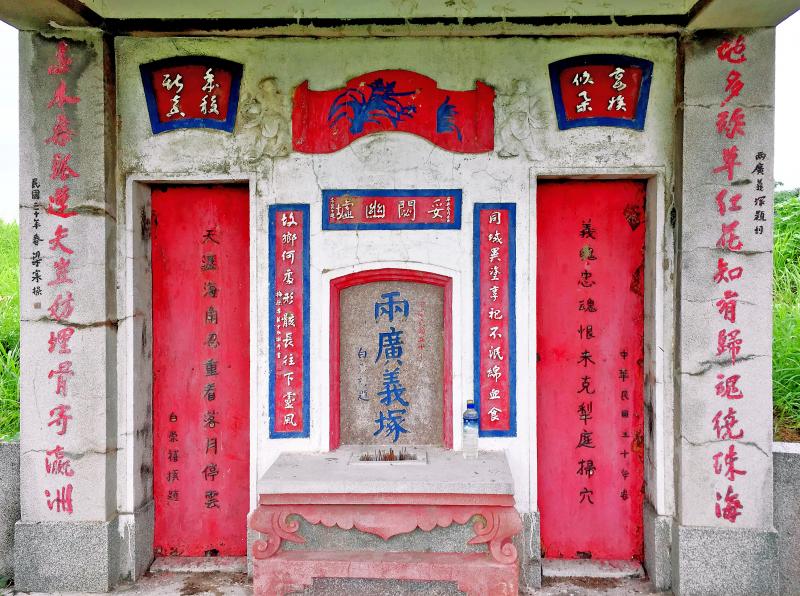

Photo: Linda Gail Arrigo

It has been barely two generations, and that which seemed immutable and sacred about Taiwanese culture, the graves where families paid respects to ancestors on Tomb Sweeping Day, also known as the Qingming Festival, have been swept from the hillsides by advancing rows of apartment buildings. The new-found wealth and consumerism of the country has spawned a secular paradise of cement and marble and glass and acrylic. But does this satisfy the soul, or give meaning to the continuity of human life? Do skyscrapers evoke any historical memory?

In traditional cosmology, the signs of death were to be avoided, like infectious disease. Ghosts, the unfed ancestors of other people, might lurk nearby. In fact, if walking in cemeteries on hillsides, you might trip into holes where coffins had been exhumed so as to clean the bones and temporarily store them in pots before interment in the family crypt, the usual custom. No wonder many were glad when the government began encouraging cremation and removing graveyards, beginning over 20 years ago.

But I believe that this has gone too far, too fast and most of the historical information has already been destroyed, along with cultural artifacts. Singapore, much smaller than Taiwan, faced the same dilemma of culture and nature versus development, and found a compromise in Bukit Brown Cemetery.

Photo: Linda Gail Arrigo

In the case of the Sindian First Cemetery, which had held graves dating back to the Emperor Qianlong (乾隆, 1735-1796) as well as grand carved stone pillars from the Japanese period, the neighborhood was in 2017 promised a park. One young preservationist, Cat Shih (施其陽), was studying the early pioneer clans that settled the southern Taipei basin; others concerned were local historians and descendants of these clans. But the applications for retention of some historical gravesites were all rejected by the New Taipei City Bureau of Culture.

The trees carelessly planted in the large park, 7.6 hectares, in a few months gave way to zoning for industry, obviously the real reason for rapid clearing. This process has been recorded in a forthcoming book by James Morris, titled “Grassroots Heritage.”

Now the Nanshan graves (南山公墓) area in Tainan, just north of the airport, is about to meet the same fate, as we learned during a tour and conference in October. But Nanshan no doubt holds some of the oldest gravesites in Taiwan that are still accessible (much was already built over in the modern sprawl of Tainan City), and in fact it has the earliest known Han Chinese grave in Taiwan, dated 1642. It also contains an undisturbed area of natural plant and animal habitat along a stream, documented by Li Yen-ping (李燕萍) of the NGO Above-Ground Tainan (地上台南).

Photo: Linda Gail Arrigo

HUMAN RECORD

Since the southwest coast of Taiwan has been layered for millennia under alluvial deposits and has been extended out by about three kilometers since the Dutch period, Nanshan may well also hold artifacts of prehistory in its lower layers. Professor Lu Tai-kang (盧泰康), who scientifically excavated the area where a military village was removed and discovered 40 Qing Dynasty-era tombs not far down, says there may well be 10 layers of habitation.

As an anthropologist, I follow the news of discoveries in archeology and human evolution. Surprisingly, new human species have been recently discovered in South Africa and Southeast Asia, e.g. Homo floresiensis in Indonesia in 2003. Due to new DNA technology, with even 50,000-year-old bones yielding to genetic sequencing, the understanding of human evolution and population migrations is advancing at a breath-taking pace.

Photo courtesy of Li Yen-ping

Archaeological and genetic findings from the last few hundred years in Europe likewise have revised the understanding of historical documents and provided deeper social history; graves and bones provide evidence of class structure, epidemics and wars. Much more awaits discovery, and it is a labor-intensive effort, but its value for understanding “who are we?” is much more than can be measured by money.

Taiwan’s public cemeteries were long neglected no-mans-land, and sometimes they have become eyesores littered with trash. But that is not a justification for government to convert the land into real estate and destroy forever the cultural and historical knowledge that should belong to the nation.

Development should proceed cautiously, with careful archaeological excavation before the land is redeveloped as best for public use — not just private profit. It is long past time to take Taiwan’s history and pre-history seriously — and to allow Taiwan to participate in the increasingly sophisticated tracing of world history.

Photo courtesy of Li Yen-ping

Moreover, Taiwan needs space for breathing, physical recreation and cultural preservation much more than it needs more apartments. The population, which grew three-fold after War World II to nearly 24 million, is now beginning to shrink. Taiwan has a birthrate that is nearly the lowest in the world, at only about half of replacement. It would be advisable to rehabilitate derelict industrial land rather than trash and build over natural landscapes.

We need the self-knowledge and the sense of identity to be found through the signs of long-past generations who lived on this land.

Photo courtesy of Li Yen-ping

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

It’s an enormous dome of colorful glass, something between the Sistine Chapel and a Marc Chagall fresco. And yet, it’s just a subway station. Formosa Boulevard is the heart of Kaohsiung’s mass transit system. In metro terms, it’s modest: the only transfer station in a network with just two lines. But it’s a landmark nonetheless: a civic space that serves as much more than a point of transit. On a hot Sunday, the corridors and vast halls are filled with a market selling everything from second-hand clothes to toys and house decorations. It’s just one of the many events the station hosts,

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

Two moves show Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) is gunning for Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) party chair and the 2028 presidential election. Technically, these are not yet “officially” official, but by the rules of Taiwan politics, she is now on the dance floor. Earlier this month Lu confirmed in an interview in Japan’s Nikkei that she was considering running for KMT chair. This is not new news, but according to reports from her camp she previously was still considering the case for and against running. By choosing a respected, international news outlet, she declared it to the world. While the outside world