They’re often called “children of the stars,” and as this documentary’s Chinese title suggests, they tend to feel lost trying to navigate this earth. But in Among Us (地球迷航) the children are adults, who have been diagnosed with autism since they were young.

All four of them face different challenges, have varying degrees of independence and can appear quite neurotypical on the surface — the autism spectrum is broad, something often misunderstood by the public. Among US does a good job of portraying this range, from Ting-wei (廷瑋), who has difficulties speaking and controlling his body but is a brilliant, expressive poet, to the highly imaginative Hui-lun (惠綸), who holds several part-time jobs and at one point leaves home for a week after arguing with his mother.

Despite this, the demographic range is limited: all four subjects are males, with three of them in their 20s. While autism is generally three to four times as prevalent in boys, it would have been worthwhile to see things from a female perspective.

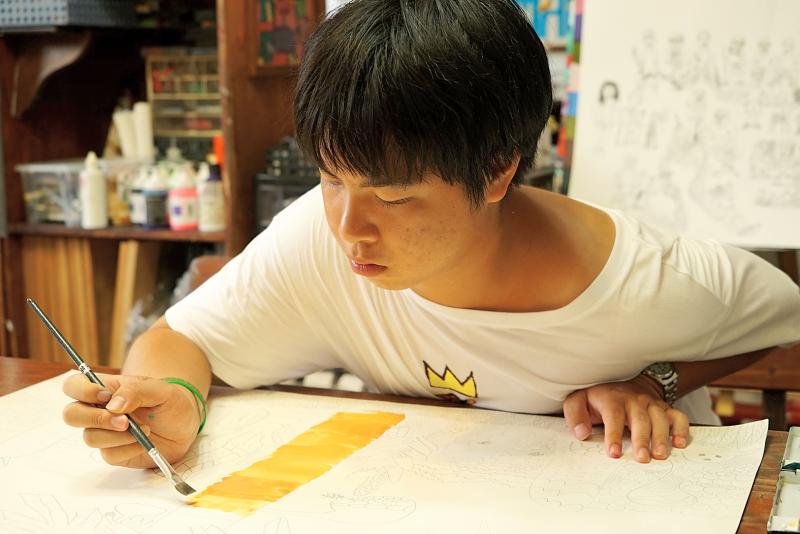

Photo courtesy of Among Us

This film is a sequel to acclaimed director Lin Cheng-sheng’s (林正盛) 2010 documentary Twinkle Twinkle Little Stars (一閃一閃亮晶晶), which portrayed four autistic children and teens. It’s a familiar topic to Lin, as his wife Han Shu-hua (韓淑華) is an art therapist who has worked with people of all ages on the autism spectrum for nearly two decades. Each film took four years to make, and the comfort level and intimacy shown in Among Us is apparent.

The impetus behind the film is DB Art Collective (多寶藝術學堂) in Taipei’s Guandu (關渡) area, which Han launched in 2016 to help people on the autism spectrum express themselves artistically, gain life skills and plan activities. To spread awareness about autism, Lin launched a crowdfunding project to get the film into theaters and also have it sent to elementary schools.

The art collective is a wonderful conduit to portray the creativity and rich inner worlds of the subjects. All of them have loving parents who encourage them to express themselves through poetry, art and music. A big part of the film revolves around this relationship, which is not always easy, and the parents worry about what will happen to their children after they’re gone.

Photo courtesy of Among Us

Lin portrays the subjects’ vibrant imaginations, and they feel quite comfortable sharing their inspiration with the camera, expressively drawing or playing music.

Despite their talents, Lin doesn’t sugarcoat their situation or hype up their abilities, as autistic people being geniuses is a common stereotype, although only 10 percent of those with autism are savants. It’s more of a matter-of-fact, direct portrayal that isn’t sensational or emotional; they’re just as human as everyone else, just a bit different.

Although the cutesy animations and bouncy electronic soundtrack implies these adults are childlike, it does reflect their whimsical and fantastic inner worlds and serves to lighten the mood. Despite their many interests and evident progress during the time Lin has known them, the hard truth is they aren’t able to live regular lives, something that they are acutely aware of and upset about.

Photo courtesy of Among Us

As Ting-wei types in one scene, “My teachers told me that I would never be able to learn; I was anguished, I was furious but I couldn’t speak and refute them.”

“I want to go somewhere in outer space,” he types in another scene.

As society increasingly embraces cultural diversity, one message that the film sends to the viewer is that people who are neurologically different have much to offer.

Photo courtesy of Among Us

The film doesn’t reach any conclusions about how the subjects can survive and even thrive after their parents pass away, or explore what happens to those with less supportive or resourceful families, but the first step is to promote understanding so that there is even the possibility of a friendly future where they can exist among us. This touching documentary does just that.

Taiwan can often feel woefully behind on global trends, from fashion to food, and influences can sometimes feel like the last on the metaphorical bandwagon. In the West, suddenly every burger is being smashed and honey has become “hot” and we’re all drinking orange wine. But it took a good while for a smash burger in Taipei to come across my radar. For the uninitiated, a smash burger is, well, a normal burger patty but smashed flat. Originally, I didn’t understand. Surely the best part of a burger is the thick patty with all the juiciness of the beef, the

The ultimate goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the total and overwhelming domination of everything within the sphere of what it considers China and deems as theirs. All decision-making by the CCP must be understood through that lens. Any decision made is to entrench — or ideally expand that power. They are fiercely hostile to anything that weakens or compromises their control of “China.” By design, they will stop at nothing to ensure that there is no distinction between the CCP and the Chinese nation, people, culture, civilization, religion, economy, property, military or government — they are all subsidiary

This year’s Miss Universe in Thailand has been marred by ugly drama, with allegations of an insult to a beauty queen’s intellect, a walkout by pageant contestants and a tearful tantrum by the host. More than 120 women from across the world have gathered in Thailand, vying to be crowned Miss Universe in a contest considered one of the “big four” of global beauty pageants. But the runup has been dominated by the off-stage antics of the coiffed contestants and their Thai hosts, escalating into a feminist firestorm drawing the attention of Mexico’s president. On Tuesday, Mexican delegate Fatima Bosch staged a

Would you eat lab-grown chocolate? I requested a sample from California Cultured, a Sacramento-based company. Its chocolate, not yet commercially available, is made with techniques that have previously been used to synthesize other bioactive products like certain plant-derived pharmaceuticals for commercial sale. A few days later, it arrives. The morsel, barely bigger than a coffee bean, is supposed to be the flavor equivalent of a 70 percent to 80 percent dark chocolate. I tear open its sealed packet and a chocolatey aroma escapes — so far, so good. I pop it in my mouth. Slightly waxy and distinctly bitter, it boasts those bright,