Can the People’s Republic of China (PRC) invade and conquer Taiwan? Experts differ, but most of the current debate considers only the military balance, and whether the PLA has the weapons, hardware and capabilities to get ashore, defeat Taiwan’s military and force Taiwan to surrender.

The military match up is important, but it misses half the picture — and half of the PRC’s strategy against Taiwan.

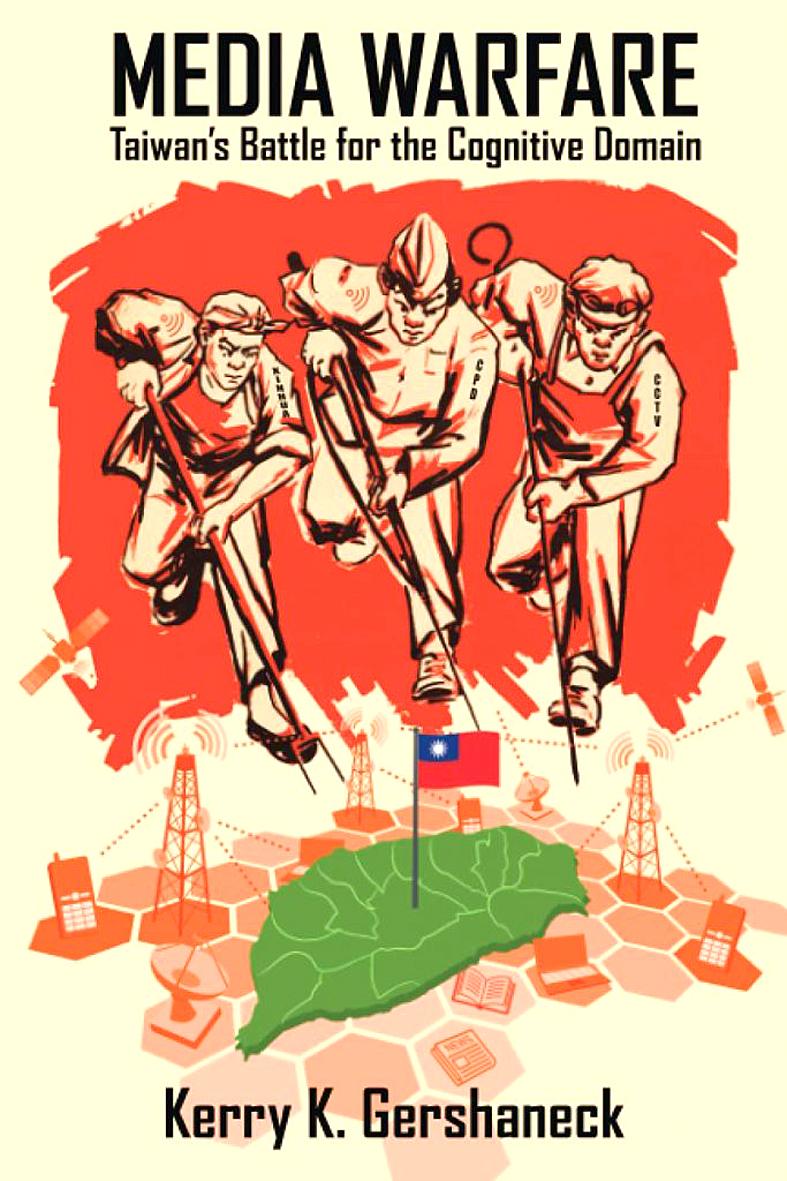

Kerry Gershaneck’s new book, Media Warfare: Taiwan’s Battle for the Cognitive Domain, details and explains a key portion of that other half: the PRC’s use of “media warfare” to psychologically fracture and demoralize Taiwan and make conquest easier or, even better for Beijing, to have Taiwan give up without a fight.

Gershaneck knows the topic well, having vast Asia and hands-on strategic communications experience at all levels of the US government, as well as a particularly useful counterintelligence background. Last year, he published a seminal work on PRC Political Warfare: Political Warfare: Strategies for Combating China’s plan to “Win without Fighting.”

This time, Gershaneck focuses on what China has done and is doing to Taiwan on the media warfare front. As important, he lays out how Beijing is waging the same type of insidious warfare worldwide — especially against Taiwan’s main ally the US. As Yu Tsung-chi (余宗基), one of Taiwan’s foremost experts on China’s political warfare, notes in his powerful foreword to the book, Taiwan is China’s “test case” for developing strategies and tactics to attack other countries.

To Chinese strategists, media warfare (and the broader political warfare effort of which media warfare is part) is just as important as building the PLA into a force able to defeat the US military. Indeed the kinetic and the informational are considered mutually reinforcing lines of attack.

INSTRUMENTS OF MEDIA WARFARE

“Media warfare” — also known as “public opinion warfare” — leverages all instruments that inform and influence an adversary’s public and government opinion. The objective is to weaken, divide, corrode, confuse, co-opt and demoralize an opponent.

What are the instruments? The old standards such as television, radio and newspapers, of course. But there are also books, textbooks and over the past three decades the Internet and social media. Indeed, the Chinese communists make full use of all of these, and are particularly aggressive on the Internet/social media vectors.

This makes sense. With newspapers, TV and radio a propagandist has to somehow lure the intended target to receive the message. With social media and the Internet it is possible to “jam” the message into the target non-stop. And given that a huge majority of Taiwan’s public is active on social media, it presents a particularly target rich environment.

What does the PRC’s media warfare campaign against Taiwan look like? In order to deliver its messages, Chinese entities have bought Taiwanese broadcasting outlets and newspapers, and use the lure of advertising dollars against independent outlets. Another key part of the effort to shape the views of as wide an audience as possible is the aggressive use of social media platforms to influence, confuse and deceive, often through effective profiling of users to better target messaging.

How successful has Beijing been? In 2018, the PRC deployed media warfare stratagems, including heavy use of social media, to engineer the election of an absolute nobody — Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) candidate Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) — as the mayor of Kaohsiung. Many in the KMT support communist China’s plans to annex Taiwan. The surprise election of Han to this powerful mayorship was no small feat and no minor issue: Kaohsiung has historically been a stronghold of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which firmly opposes annexation by China.

As part of the effort to elect Han, pro-Beijing media in Taiwan and the communist propaganda organs in China relentlessly attacked DPP leadership, including President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), with disinformation and untrue allegations. That relentless campaign interference was enough to raise doubts with voters, especially because there were no effective means in Taiwan to detect and counter the media warfare attacks.

Han ran for president under the KMT banner two year’s later, once again with pro-China Taiwanese and communist China-based media warriors hard at work on his behalf. Han had a fair shot at winning, but two things happened: First, Taiwan’s government woke up to the media warfare threat and cobbled together effective-enough defenses to derail and expose Beijing’s strategy. Second, the Chinese communist crushing of Hong Kong’s pro-freedom movement a few months before Taiwan’s election awakened a huge chunk of Taiwan’s public to the Chinese threat — and inoculated many to Chinese subversion.

Gershaneck provides a concise, yet detailed introduction to media warfare in Taiwan, but with larger implications. He walks the reader through the confusing and redundant terminology and explains how media warfare fits into the larger Chinese political warfare strategy — intended to defeat an enemy via all measures short of outright kinetic warfare.

While using Taiwan as the focus of his latest book, Gershaneck emphasizes that what the PRC is doing to Taiwan it is also doing to the US and other free nations.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The author wrote his most recent book to help Western nations “better detect, deter, counter and defeat” Chinese media warfare — and political warfare writ large. And he provides a set of practical recommendations for Taiwan’s government that are applicable to any country under PRC media warfare attack.

For example, Chinese state-controlled media (which is every media entity operating in China) has formed strategic alliances with Western media. The New York Times, Washington Post and even the conservative and so-called tough on China Wall Street Journal carried China Daily media warfare inserts for a number of years. Gershaneck also describes how the Chinese government takes control of newspapers and broadcast media serving the Chinese diaspora in many, if not most, countries.

And, at the same time the PRC floods the US with “reporters” — it makes life miserable in China for the few foreign reporters still allowed to operate there. And US and other foreign outlets routinely self-censor to avoid angering Beijing.

Gershaneck paints a grim picture of China’s massive, well funded and effective media warfare effort against Taiwan, and worldwide.

Yet, many — if not most — people will say they are too smart, too well educated and too discerning to be influenced by Beijing’s media warfare, induced propaganda. Maybe so. But if you’ve ever said or thought any of the following, you’ve been influenced.

■ COVID-19 couldn’t possibly have come from a laboratory.

■ China wants to “reunify” with Taiwan.

■ The US must have China’s help on climate change, North Korea and (fill-in-the-blank).

■ We simply have to be invested in the China market.

■ To make China an enemy, treat it like one.

■ China is no longer communist. It is capitalist.

■ China’s rise is “peaceful” and inevitable.

■ China has never attacked its neighbors.

■ China is not expansionist.

■ China is just doing what all great powers do.

Gershaneck’s book is indeed alarming — though one grudgingly admires China’s industriousness and persistence on the “non-kinetic” media/public opinion/psychological fronts.

But certainly the US Government has its own media warfare and political warfare effort to match and defeat whatever Beijing is doing?

If only. Unlike previous administrations, the Trump Administration understood the problem, and also understood China’s political warfare efforts. It had some limited success exposing and cracking down here and there, with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (to whom the book is dedicated) and former deputy national security advisor, Matthew Pottinger being particularly effective. But they ran out of time.

The US Government is once again back to doing nothing while China runs wild in the crucial cognitive battlefield that Professor Gershaneck explains so well in this important book.

This isn’t surprising, one supposes. The recent collapse of the Afghan government and military was as much a political warfare victory for the Taliban as a military victory.

The US military and civilian leadership didn’t seem to notice.

One hopes they take the China’s version of the media and political warfare threat more seriously. And then do something about it.

Reading Gershaneck’s books would be a good start.

Grant Newsham is a retired US Marine and a former diplomat and business executive who spent many years in Asia. He is a senior fellow with the Center for Security Policy.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

It’s an enormous dome of colorful glass, something between the Sistine Chapel and a Marc Chagall fresco. And yet, it’s just a subway station. Formosa Boulevard is the heart of Kaohsiung’s mass transit system. In metro terms, it’s modest: the only transfer station in a network with just two lines. But it’s a landmark nonetheless: a civic space that serves as much more than a point of transit. On a hot Sunday, the corridors and vast halls are filled with a market selling everything from second-hand clothes to toys and house decorations. It’s just one of the many events the station hosts,

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

Two moves show Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) is gunning for Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) party chair and the 2028 presidential election. Technically, these are not yet “officially” official, but by the rules of Taiwan politics, she is now on the dance floor. Earlier this month Lu confirmed in an interview in Japan’s Nikkei that she was considering running for KMT chair. This is not new news, but according to reports from her camp she previously was still considering the case for and against running. By choosing a respected, international news outlet, she declared it to the world. While the outside world