Only two men in the Communist Party’s history have ever written a so-called historical resolution. China is waiting to see whether President Xi Jinping (習近平) becomes the third.

The first official declaration on Chinese history in 40 years is set to top the agenda when the ruling party huddles this week in the last major meeting before a twice-a-decade congress next year, where Xi’s expected to break precedent and secure a third term to extend his indefinite rule.

Mao Zedong (毛澤東) and Deng Xiaoping’s (鄧小平) historical resolutions came at critical junctures in the nation’s trajectory and enabled their authors to dominate party politics until their dying breaths. Issuing his own magnum opus would not only put Xi on par with those party titans, but could signal big changes afoot in the world’s second-largest economy.

Photo: AFP

The meeting, which began yesterday and runs until Thursday, called the sixth plenum, kicks off the closest thing China has to a campaign season. Getting the party to back his take on China’s history — and its future — would be the biggest sign yet that Xi has the power base to potentially rule for life after almost a decade of purging enemies and pushing to foster national pride.

WHAT IS THE SIXTH PLENUM?

Between each party congress, the Communist Party’s Central Committee meets seven times in meetings called plenums that cover different topics. About 400 men (and a handful of women), including state leaders, military chiefs, provincial bosses and top academics, convene at a heavily guarded military hotel in Beijing. Like most things in elite Chinese politics, the agenda is top secret and only revealed in a communique afterward — with any squabbling and infighting edited out.

As the last big meeting in China’s five-year political cycle, the sixth plenum is in some ways more important than others: It’s the final chance for horse trading before big decisions are made at the following year’s congress. In preparation, the party’s Poltiburo last month reviewed a draft resolution on “the major achievements and historical experiences of the party’s 100 years,” the official Xinhua News Agency said, without elaborating.

The wording raised eyebrows. At the sixth plenum in 1981, Deng famously passed his historical resolution denouncing the missteps of Mao, whose Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution crusades caused famine and death. At a similar summit in 2016, the party named Xi a “core” leader, a term previously reserved for Deng, Mao and Jiang Zemin (江澤民) that confers de facto veto powers over key decisions.

WHAT ARE HISTORICAL RESOLUTIONS?

At face value, they’re long, dry accounts written in unwieldy party-speak. In reality, they’re the ultimate power play.

When Mao published his historical resolution in 1945, the People’s Republic was four years away from being a country and still tangled in leadership wars. The document, titled Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party, ended all that uncertainty. It declared that only Mao had the “correct political line” to lead the CCP, clearing the way for decades of his personality-driven rule.

By the time Deng delivered his document in 1981, the party was facing another leadership tussle in the wake of Mao’s death four years earlier. Weaving a narrative that condemned the chaos of Mao’s Cultural Revolution without totally discrediting him, and thus undermining the party, Deng secured his position as the man with the right vision to take China forward.

That platform allowed Deng to liberalize China’s economy and ban another “cult of personality” without ever being the president. The resolutions carry such weight because the party revolves around what Wu Guoguang, professor of history at the University of Victoria in Canada, calls “documentary politics” — a system where elite decisions are ratified in documents, not laws.

“The writing process of a CCP document is a process of consensus building within the party elite,” Wu said, making such a publication the biggest available show of collective approval. Deng canvassed more than 4,000 cadres’ opinions on his resolution, and state media has reported that Xi is currently presenting his to key people outside the party.

Still, Wu said the leader always controls the final narrative.

“Xi definitely dominates the process of the shaping of this third historical resolution,” Wu said. “He is imposing his viewpoints to become the framework within which party elites make their consensus.”

WHAT WILL XI SAY?

Unlike his predecessors who criticized party missteps, Xi’s likely to spin a victorious tale of a century of success, glossing over failures and outlining his vision for a modern Marxist society, according to signs from state media. The Politburo meeting last month declared the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation a “historical inevitability” under Xi, the party’s People’s Daily newspaper said, offering clues at the resolution’s content.

Crafting a story of continuous success requires Xi to embrace the contradictory policies of Mao and Deng, ignore the scars of events such as the Great Leap Forward and the Tiananmen Square massacre, and present his own ideology as the natural next path — despite critics’ claims he’s reviving the personality cult Deng despised.

“Blending Mao and Deng together seems illogical, but that is the political trick in playing CCP politics,” said Wu, who in the 1980s worked for the reform-minded premier Zhao Ziyang (趙紫陽), later ousted for his liberal views. “Xi is changing many policies of Deng’s, but he definitely follows both Mao and Deng in one way: to defend the CCP’s monopoly of power in China.”

WHY DOES IT MATTER?

As the leader of one-fifth of the world’s people, Xi’s potential to rule for life has huge ramifications. China’s most important man is already on a mission to redistribute the nation’s wealth to build a fairer Marxist society. That “common prosperity” campaign wiped about US$1 trillion off the value of Chinese stocks globally in July, and impacted the business of everyone from delivery drivers and after-school teachers to tech giants and celebrities, with major fallout for global investors.

With a historical resolution under his belt, Xi would head into next year’s politicking emboldened to execute more economic reforms and push back against the US on trade, coronavirus probes and, of course, Taiwan, which Beijing considers a breakaway province. Xi in July called it a “historic mission” to bring the democratic nation under the party’s control, a move that could actually send Washington and Beijing to war if done by force.

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

The following three paragraphs are just some of what the local Chinese-language press is reporting on breathlessly and following every twist and turn with the eagerness of a soap opera fan. For many English-language readers, it probably comes across as incomprehensibly opaque, so bear with me briefly dear reader: To the surprise of many, former pop singer and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ex-lawmaker Yu Tien (余天) of the Taiwan Normal Country Promotion Association (TNCPA) at the last minute dropped out of the running for committee chair of the DPP’s New Taipei City chapter, paving the way for DPP legislator Su

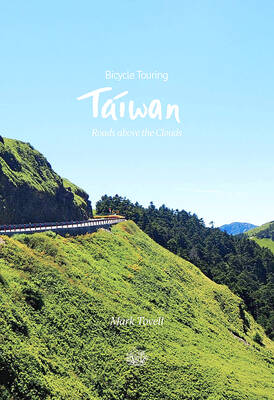

It’s hard to know where to begin with Mark Tovell’s Taiwan: Roads Above the Clouds. Having published a travelogue myself, as well as having contributed to several guidebooks, at first glance Tovell’s book appears to inhabit a middle ground — the kind of hard-to-sell nowheresville publishers detest. Leaf through the pages and you’ll find them suffuse with the purple prose best associated with travel literature: “When the sun is low on a warm, clear morning, and with the heat already rising, we stand at the riverside bike path leading south from Sanxia’s old cobble streets.” Hardly the stuff of your

April 22 to April 28 The true identity of the mastermind behind the Demon Gang (魔鬼黨) was undoubtedly on the minds of countless schoolchildren in late 1958. In the days leading up to the big reveal, more than 10,000 guesses were sent to Ta Hwa Publishing Co (大華文化社) for a chance to win prizes. The smash success of the comic series Great Battle Against the Demon Gang (大戰魔鬼黨) came as a surprise to author Yeh Hung-chia (葉宏甲), who had long given up on his dream after being jailed for 10 months in 1947 over political cartoons. Protagonist