The end of World War II left Japanese militarists with a raft of urgent problems. The Allies were about to exercise their hypocritical victor’s justice on the Japanese, which meant that many in the government and military faced jail or execution. Moreover, the Japanese establishment had lost the war badly, and for the most part run it incompetently, and had to offer a neat explanation, or at least somehow cover up its crimes, incompetence and strategic ineptitude.

As historian Bruce Lee chronicled in Marching Orders, it was Minister Okamoto Suemasa, the head of the Japanese delegation in Sweden, who came up with the approach that to this day influences virtually all discussion of the war, especially on the western left, and in Japan. After noting that the American public was shocked by the horrors of the atomic bomb, Okamoto proposed playing up the bombings to deprecate US conduct of the war and divert attention from Japan’s crimes.

On Aug. 29, 1945, he messaged Tokyo with this idea, noting: “Since it is difficult to justify the heavy damage inflicted and the massacre of hundreds of thousands of innocent people, there is the opportunity — by making use of the Diet, the radio, the various other means — to play on enemy weakness by skillfully emphasizing the extreme inhumanity of the bomb.”

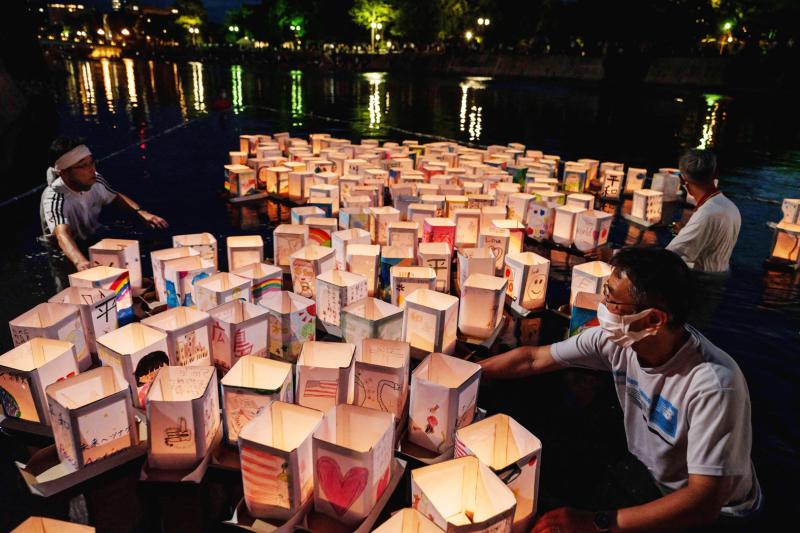

Photo: AFP

JAPAN’S A-BOMB PROPAGANDA

The Americans had been reading Japanese military and diplomatic codes, and would continue to do so until early November of 1945. US analysts summarized the burgeoning Japanese campaign for General Marshall, observing that Japanese leaders intended to play up the atomic bombings to explain Japan’s surrender, because the military did not believe it had been defeated in combat, and to counter negative publicity about Japanese atrocities, especially the treatment of Allied POWs.

In Tokyo, Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru responded enthusiastically on Sept. 13, circulating a long message about the A-bomb to several Japanese missions overseas, summarizing: “Since the Americans have recently been raising an uproar about the question of our mistreatment of prisoners, I think we should make every effort to exploit the atomic bomb question in our propaganda.”

Photo: AFP

In reply, Okamoto in Sweden and Shunichi Kase, the representative in Switzerland, warned that Japan must give every appearance of not having such a propaganda campaign. Okamoto suggested that Japan must “[h]ave announcements made exclusively for home consumption and have the Anglo-American news agencies carry these announcements ... have Anglo-American newspapermen write stories on the bomb damage and thus create a powerful impression abroad.”

Oddly enough, while today this message is ideological gospel for many lefties in the West, it was on the US right that many of these criticisms first appeared in the mainstream media. Barton Bernstein, the noted historian of the atomic bomb, described this in a 2014 piece: “American conservatives are the forgotten critics of the atomic bombing of Japan.”

He cited Medford Evans, the well-known conservative, who contended in William F Buckley’s National Review in 1959 that “The indefensibility of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima is becoming a part of the national conservative creed.”

Just the year before, Bernstein noted, the National Review had run an anti-atomic bomb article, “Hiroshima: Assault on a Beaten Foe.”

As Bernstein describes, several shibboleths of A-bomb revisionism, including the claim that the US had prolonged the war just to drop the A-bomb, had their origins in conservative attacks on the bomb (and by extension, then-president Harry Truman and the Democrats). Later the mainstream left picked up the revisionist chorus and amplified it, while today’s rightists respond to these attacks by labeling them “Un-American.”

Thus proving, once again, that historical irony is the gods’ preferred mode of communication with humankind.

Probably most readers are unaware of this history.

Karel van Wolferen described how this came about in his classic 1989 work The Enigma of Japanese Power.

“Access to the necessary personal contacts and institutions is a great problem for businessmen and scholars working in Japan, who are therefore acutely aware that a genuinely critical stance may close many doors,” he wrote. “A combination of money and the need for access, as well as political innocence, has bred large numbers of Japan specialists who are in varying degrees — however unwittingly — apologists for Japan.”

BEIJING’S UNITED FRONT

Sound familiar? Van Wolferen could well be describing China and its propaganda campaigns today. Indeed, the prototype of the Chinese propaganda ops was the highly successful Japanese revision of the history of the end of World War II. Unlike with Beijing’s United Front campaign, an operation so obvious there is even a name for it in Western scholarly and journalistic writing, the Japanese propaganda operation has operated in darkness, largely unknown.

The Japanese had a couple of advantages that Beijing does not. Though the fact that the US was reading Japanese diplomatic and military codes was tragically made public in November of 1945, the messages themselves and many other facts about the code-breaking operations remained classified for decades afterwards. The Japanese campaign on the end of the war was thus launched into a space unoccupied by a history that might give lie to its claims.

The second advantage is that the end of the war is history, receding rapidly into the past, which has to be studied. The Japanese wartime government can add no fresh atrocities, being seven decades dead.

By contrast, Beijing’s propaganda campaign is current events, its atrocities in Tibet, East Turkestan and elsewhere living news, not dead history. Moreover, Beijing is the clear enemy of the current world order dominated by the US, while after World War II, Japan became an approved supporter of that order.

All of the claims and responses that are now made about the atomic bombings and the end of the war have their parallels in Beijing’s responses to western critics of China’s behavior: they do not understand China (Japan). Their criticisms are motivated by racism (the area bombing campaign of Japanese cities was motivated by racism).

Chinese scholars writing in western scholarly journals and media forward Chinese propaganda claims, just as many Japanese war criminals went on to enter the postwar political system, occupy positions of power and reshape the war history for their own ends.

The Japanese idea that as a unique people, they suffered uniquely thanks to the atomic bomb, “a national martyrdom” as Wolferen puts it, is simply a racist inversion of history that wipes out the sufferings of the real victims of World War II in Asia, the Chinese and the colonized peoples of the several empires that fought each other. Chinese accusations of racism invert history the same way — making Han Chauvinism disappear to paint racism as solely a Western problem.

In November of 1944 Kajima Construction Company, a Japanese industry giant, began construction of over 10km of tunnels under mountains in Nagano prefecture in Japan to house the Imperial military HQ when the Americans invaded. Something like 7,000 Korean slaves were used. The firm’s head, Kajima Morinosuke, in the postwar era entered the National Diet’s House of Councilors as a prominent philanthropist, scholar and writer of Japan’s diplomatic histories.

That is one reason why the reader has probably never heard of this last stand redoubt, or the hundreds of other similar if smaller tunnels. Now, imagine what you would know about Xinjiang slave labor if the Chinese and western firms that used it also controlled all the news and history about Xinjiang.

Welcome to Japan’s United Front.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Politically charged thriller One Battle After Another won six prizes, including best picture, at the British Academy Film Awards on Sunday, building momentum ahead of Hollywood’s Academy Awards next month. Blues-steeped vampire epic Sinners and gothic horror story Frankenstein won three awards each, while Shakespearean family tragedy Hamnet won two including best British film. One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosive film about a group of revolutionaries in chaotic conflict with the state, won awards for directing, adapted screenplay, cinematography and editing, as well as for Sean Penn’s supporting performance as an obsessed military officer. “This is very overwhelming and wonderful,” Anderson