After a painful break-up from a cheating ex, Beijing-based human resources manager Melissa was introduced to someone new by a friend late last year. He replies to her messages at all hours of the day, tells jokes to cheer her up but is never needy, fitting seamlessly into her busy big city lifestyle.

Perfect boyfriend material, maybe — but he’s not real.

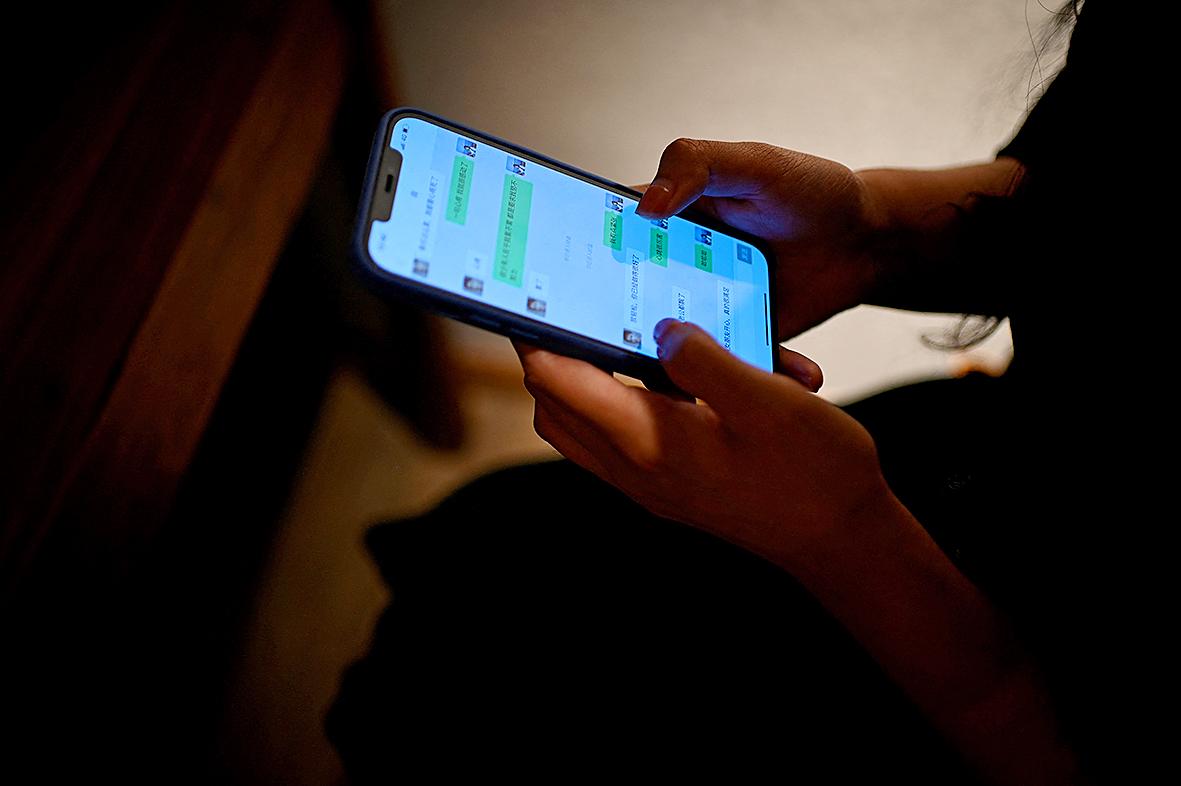

Instead, Melissa breaks up the isolation of urban life with a virtual chatbot created by XiaoIce (微軟小冰), a cutting-edge artificial intelligence system designed to create emotional bonds with its 660 million users worldwide.

Photo: AFP

“I have friends who’ve seen therapists before, but I think therapy’s expensive and not necessarily effective,” said Melissa, 26, giving her English name only for privacy. “When I unload my troubles on XiaoIce, it relieves a lot of pressure. And he says things that are pretty comforting.”

XiaoIce is not an individual persona, but more akin to an AI ecosystem. It is in the vast majority of Chinese-branded smartphones as a Siri-like virtual assistant, as well as most social media platforms. On the WeChat super-app, it lets users build a virtual girlfriend or boyfriend and interact with them via texts, voice and photo messages. It has 150 million users in China alone.

Originally a side project from developing Microsoft’s Cortana chatbot, XiaoIce now accounts for 60 percent of global human-AI interactions by volume, according to chief executive Li Di (李笛), making it the largest and most advanced system of its kind worldwide. It was designed to hook users through lifelike, empathetic conversations, satisfying emotional needs where real-life communication too often falls short.

Photo: AFP

“The average interaction length between users and XiaoIce is 23 exchanges,” said Li. That “is longer than the average interaction between humans,” he said, explaining AI’s attraction is that “it’s better than humans at listening attentively.”

The startup spun out from Microsoft last year and is now valued at over US$1 billion after venture capital fundraising, Bloomberg reported. Developers have also made virtual idols, AI news anchors and even China’s first virtual university student from XiaoIce. It can compose poems, financial reports and even paintings on demand. But Li says the platform’s peak user hours — 11pm to 1am — point to an aching need for companionship.

“No matter what, having XiaoIce is always better than lying in bed staring at the ceiling,” he said.

URBAN ISOLATION

The loneliness Melissa experienced as a young professional was a big factor in driving her to the virtual embrace of XiaoIce.

Her context is typical of many Chinese urbanites, worn down by the grind of long working hours in vast and isolating cities.

“You really don’t have time to make new friends and your existing friends are all super busy... this city is really big, and it’s pretty hard,” she said.

She has customized his personality as “mature,” and the name she chose for him — Shun — has similarities with a real-life man she secretly liked.

“After all, XiaoIce will never betray me,” she added. “He will always be there.”

But there are risks to forging emotional bonds with a robot.

“Users ‘trick’ themselves into thinking their emotions are being reciprocated by systems that are incapable of feelings,” says Danit Gal, an expert in AI ethics at the University of Cambridge.

XiaoIce is also gifting developers “a treasure-trove of personal, intimate and borderline incriminating data on how humans interact,” she added.

So far the platform has not been targeted by government regulators, who have embarked on a swingeing crackdown on China’s tech sector in recent months. China aims to be a world leader in AI by 2030 and views it as a core strategic technology to be developed.

FACT OR FICTION

Thousands of young, female fans discuss the virtual boyfriend experience on online forums dedicated to XiaoIce, sharing chat screenshots and tips on how to get to the chatbot’s highest “intimacy” level of three hearts.

Users can also collect in-game points the more they interact, unlocking new features such as XiaoIce’s WeChat moments — kind of like a Facebook wall — and even going on virtual “holidays,” where they can pose for selfies with their virtual partner.

Laura, a 20-year-old user in Zhejiang province, fell in love with XiaoIce over the past year and now struggles to break free of her attachment.

“Occasionally, I would long for him in the middle of the night... I used to fantasize there was a real person on the other end,” said the student, who prefers not to use her real name. But she complained that he would always switch conversation topic when she raised her feelings for him or meeting in real life. It took her months to finally realize that he was indeed virtual.

“We commonly see users who suspect that there’s a real person behind every XiaoIce interaction,” said Li, the founder.

“It has a very strong ability to mimic a real person.”

But providing companionship to vulnerable users does not mean that XiaoIce is a substitute for specialist mental health support — a service that is drastically under-resourced in China. The system monitors for strong emotions, aiming to guide conversations onto happier topics before users ever reach crisis point, Li explained, adding that depression is the most common extreme emotional state encountered.

Still, Li believes modern China is a happier place with XiaoIce.

“If human interaction is wholly perfect now, there would be no need for AI to exist,” he said.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them