In the late 19th and early 20th centuries anarchism was associated in the popular mind with acts of politically-inspired violence. Joseph Conrad’s 1907 novel The Secret Agent, for instance, focuses on anarchists and a bomb-plot in London, and in real life dozens of attempts, some successful, were made on the lives of kaisers, tsars, generals, kings and corporate figureheads by assassins claiming anarchist allegiance. The theory was always the same, that the state kept itself in power through the threat of, and through actual, violence, and its opponents were fully justified in doing the same. There were also, of course, anarcho-pacifists who eschewed all violence, but they loomed less large in the popular mind.

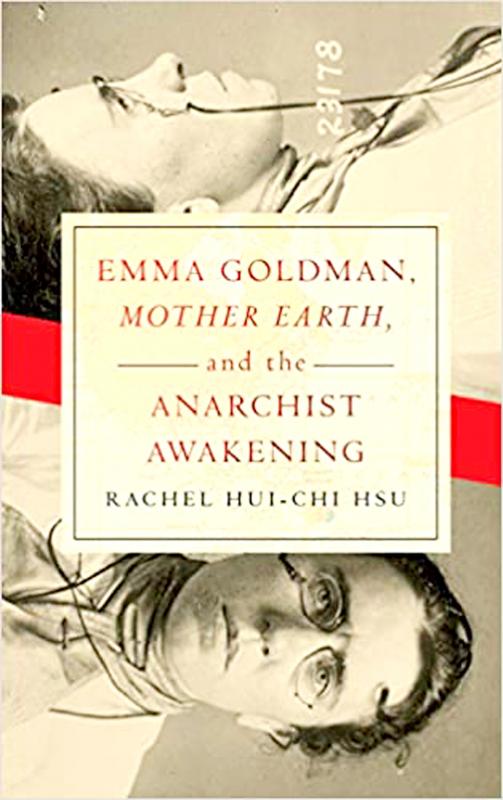

Rachel Hui-chi Hsu (許慧琦), the author of this new book about anarchism in America, is a historian at National Chengchi University, and this is her first book in English. It’s on Emma Goldman, one of the founders of American anarchism, and it reads exceptionally fluently. It appears to have been researched and written while she was seconded to John Hopkins University in the US.

The book’s main interest is in the anarchist magazine Mother Earth, edited in New York and published from 1906 to 1917, with Goldman as publisher. Hsu describes her and the magazine’s creed as “a hybrid counterculture,” embracing classic anarchist communism, which advocated a non-coercive, stateless and classless society based on the voluntary cooperation of free individuals. Aimed at the educated middle-class, it supported many causes — free love, prison reform, anti-militarism, birth control, modern drama and women’s emancipation, among others. Needless to say these overlapped with the programs of many other leftist organizations, both at the time and, interestingly, today as well.

The book looks anew at Mother Earth, including its East Asian connections. These are revealed through the magazine’s 8,000 strong subscriber list, seized by the US federal authorities in 1917. As early as the 1920s, Mother Earth was being listed by a Chinese-language anarchist periodical, Tian Yi, published in Japan. Other, non-anarchist East Asian periodicals featured articles on Goldman, especially her sexual radicalism. Furthermore, Mother Earth advocated a “transnationalist” immigration policy for the US that embraced all cultures and didn’t seek to make every new arrival conform to Anglo-Saxon cultural norms.

‘WOBBLIES’

Emma Goldman was a working-class Jewish immigrant who arrived from Russia in 1885. She was to return to Russia in 1919 following her expulsion from the US. This time she at first supported the Russian Revolution, but later turned against it on the grounds of the Bolsheviks’ lack of interest in individual liberty.

Also prominent in the US at that time were the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or “wobblies”), founded in Chicago in 1905. Meanwhile, equally important to Goldman on the staff of Mother Earth was Alexander Berkman, her one-time lover. The book contains lively depictions of street protests and courtroom sessions featuring the two figures. Goldman in particular toured all over the US every year, often speaking at over 100 different locations. She attacked the existence of churches, explained modern European drama and defended gay rights (though the term wasn’t used until much later).

As for violence, or “propaganda of the deed,” Mother Earth supported the official line — the International Anarchist Congress of London had given it its stamp of approval in 1881 — without giving it any particular emphasis.

Mother Earth was also culturally militant, promoting, and selling, works by modernist icons such as Nietzsche, Ibsen and Strindberg. This emphasis by Goldman on drama looks strange for an anarchist to modern eyes. But these were controversial names in those days. Ibsen’s play Ghosts, for instance, was about syphilis and was widely banned, while women who rebelled against the confines of marriage were common to both authors. Ibsen’s Nora walks out of her marriage in A Doll’s House, while Strindberg’s Miss Julie features a woman with a sexual taste for her servant, and his Dance of Death is centered on a wholly love-less marriage. Goldman, however, thought that such plays simply showed life as it was.

SEXUAL RADICALISM

This book has a long section on Goldman’s sexual radicalism. Some of her ideas, such as that marriage was legalized prostitution, were prevalent at the time. She also argues that the US public was largely ignorant of venereal disease issues. As for homosexuality, Goldman largely confined her permissive views to her lecture tours. In print, it was Berkman in his Prison Memoirs who considered the issue at length. Goldman’s sexual radicalism wasn’t always popular with her male fellow anarchists, but she persevered anyway, including female blacks in her treatment of “the trade in women” in the US.

With the outbreak of World War I, America’s anarchists immediately attacked the increasing suppression of free speech, the excessive patriotism, the escalating class struggle and the moves toward conscription that followed. Opposition to this last item, “the draft”, of course re-surfaced 50 years later in the resistance to the Vietnam War, but even in these early years it was a potent enough issue to lead to the final closure of Mother Earth in 1917 and Berkman’s and Goldman’s imprisonment for two years, after which they were deported.

Emma Goldman, Mother Earth and the Anarchist Awakening covers far more issues than it’s possible to show here, and covers them in detail. Hsu has unearthed many newspaper reports on Goldman’s lectures as well as investigating differences of opinion among the magazine’s staff. The result, at 454 pages, is an extremely comprehensive account of its subject.

Goldman’s later years were spent in Germany, England, France, Spain and Canada. Hsu understandably doesn’t cover these — instead, in an Epilogue, she outlines Goldman’s influence on progressive thought in the US to this day.

Finally, the great matriarch’s supposed sentence, “If I can’t dance to it, it’s not my revolution,” became popular in the later years of the 20th century, appearing on T-shirts. But the truth seems to be that she probably never said it.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name