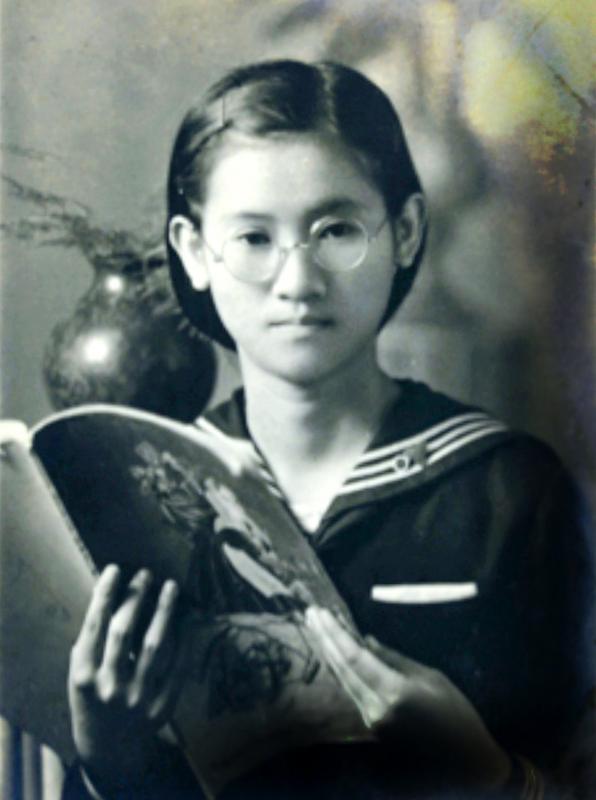

July 19 to July 25

The little girl clutched on to her mother and repeatedly cried, “My mom isn’t a bad person, don’t execute her!” She was born and raised in prison, and most likely knew what it meant when an inmate was abruptly handcuffed and dragged away.

The guards ignored her cries, and Ting Yao-tiao (丁窈窕), her mother, met her end that day by firing squad.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It was July 24, 1956, two years after Ting and her close friend Shih Shui-huan (施水環) were arrested for allegedly spying for the “communist bandits.” Both women were executed that day, and later accounts indicate that they were likely innocent victims of a fabricated accusation. Ting was 28, Shih was 29.

Although the bulk of White Terror victims were men, there were also numerous women who were arrested and executed under suspicion of working for the Chinese Communist Party. According to Women and White Terror Political Incidents (女性與白色恐怖政治事件), a paper by Yang Tsui (楊翠), 26 women were confirmed to have been executed. The real number is probably higher. Like Ting and Shih, most of them were educated, working women in their 20s. Quite a few raised their children in jail.

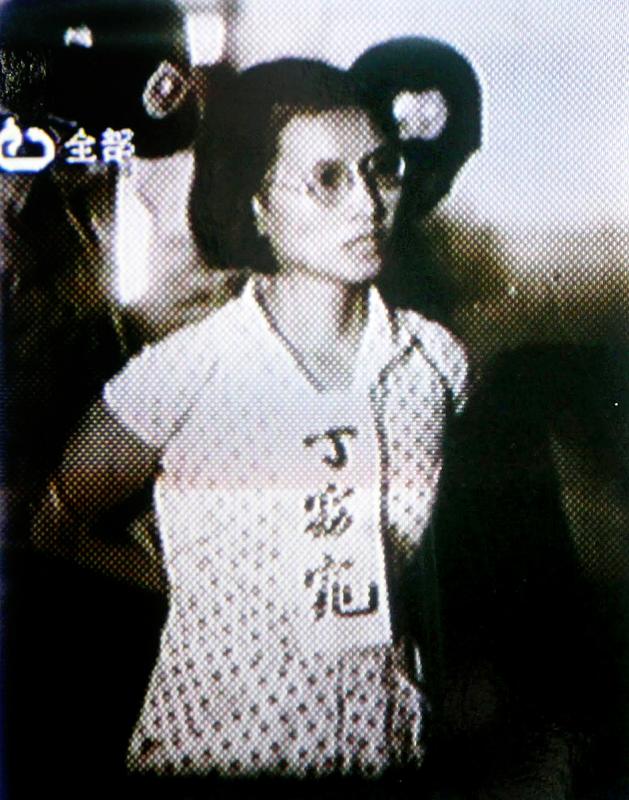

Survivor Chang Chang-mei (張常美) recalls the terrible conditions and the torture they endured, and recalls watching at least seven cellmates being carted off to the execution grounds. She clearly remembers Ting’s daughter crying that day. In a 2015 Human Rights Museum documentary, where she was the only female interviewee, Chang says she will never forgive the government.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“I’m not that generous,” Chang says.

TROUBLE BREWING

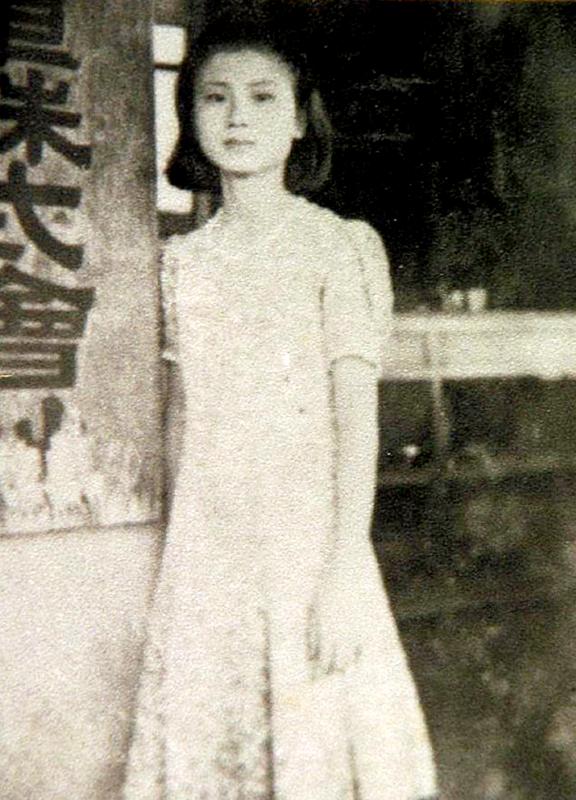

Shih and Ting met while working for the Post, Telephone and Telegraph Administration in Taipei. They later served together at a post office in Tainan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

According to an article on the Taiwan Association of Truth and Reconciliation Web site, trouble began when a man began pursuing romantic relations with Shih. Ting had doubts about his character, and advised Shih to stay away from him. In revenge, the man tried to report Ting as a communist spy to the authorities after spotting a banned book on her desk.

Fortunately, Ting’s colleague Wu Li-shui (吳麗水) intercepted the letters and burnt them.

Several years earlier, the Post, Telephone and Telegraph Administration was caught up in a White Terror incident. According to government sources, the Chinese communists had sent two secret agents to Taiwan, who, with the help of Taiwanese communist Tsai Hsiao-chien (蔡孝乾), quickly infiltrated the office’s institutions and set up four cells under the guise of teaching Mandarin. Tsai joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) after he was arrested in 1950, which led to the exposure of the operation. Up to 35 people from the Post, Telephone and Telegraph Administration’s Taipei office were arrested as a result.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Two years later, Shih’s younger leftist brother Shih Chih-cheng (施至成) ran afoul of the government and went into hiding. He spent two years living in the ceiling of Shih’s residence.

In 1954, the authorities continued their purge of the Post, Telephone and Telegraph Administration by raiding its branch in Tainan. This was allegedly sparked by the detainment of an employee in Keelung, who admitted to badmouthing the government but added that he had heard these things from Wu while working in Tainan. Wu was soon arrested, and after being severely tortured, he admitted to burning the letters and committing other crimes of subversion.

Ting’s verdict states that she was sent by the communist agents in the Taipei office to establish a youth branch in Tainan, with Wu serving as secretary. Shih was accused of joining the branch and introducing two “bandits” to Ting.

AWAITING THEIR FATE

There is no evidence that this branch, nor several of the organizations mentioned in the verdict, ever existed. Coworker Lei Shui-chuan (雷水湶), who managed to avoid his own death sentence, claims that the secret police made everything up.

Ting was likely arrested because of the letters, and Shih was probably nabbed for harboring her brother. He fled after her arrest, and while several people served significant jail time for helping him, he was never found.

Shih wrote 68 letters to her family during her incarceration.

“Don’t you worry, I believe that a righteous judge will clear our name from this disaster. We are law-abiding citizens, and we would never dare do anything that was against the law,” she wrote in her third letter sent in October 1974.

This judge never appeared, and Shih’s condition deteriorated as she suffered from stomach pain and insomnia, and her right eye was seriously damaged during an interrogation session.

Both Ting and Shih worked in a sewing factory on the prison grounds. In her last letter back home, Shih asked her sister to send her some cloth with cute patterns to give to one of the prison children. She had converted to Christianity at the urging of her mother several months earlier.

“Every morning, I do what mother says and read the bible and pray for God’s grace,” she writes. “I hope that God’s grace falls upon our whole family. Amen.”

She was executed two days later.

One day in the hospital infirmary, Ting ran into her former lover Kuo Chen-chun (郭振純), who was awaiting sentencing for allegedly participating in seditious activities. Ting told Kuo that she had left a cigarette box in the field and asked him to retrieve it the next day. Inside it was a lock of her hair and a farewell letter.

Kuo was released from jail in 1975, and he buried the lock of hair under a Madras thorn tree at Ting’s alma mater, Tainan Girls’ Senior High School. The tree collapsed in 2015 during a typhoon, but it was revived and still stands today.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

We have reached the point where, on any given day, it has become shocking if nothing shocking is happening in the news. This is especially true of Taiwan, which is in the crosshairs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), uniquely vulnerable to events happening in the US and Japan and where domestic politics has turned toxic and self-destructive. There are big forces at play far beyond our ability to control them. Feelings of helplessness are no joke and can lead to serious health issues. It should come as no surprise that a Strategic Market Research report is predicting a Compound