Joseph Liu chose Norway for his legal studies because he wanted to learn more about human rights. But instead, he’s been fighting the Norwegian government for the past four years for the right to use his national identity.

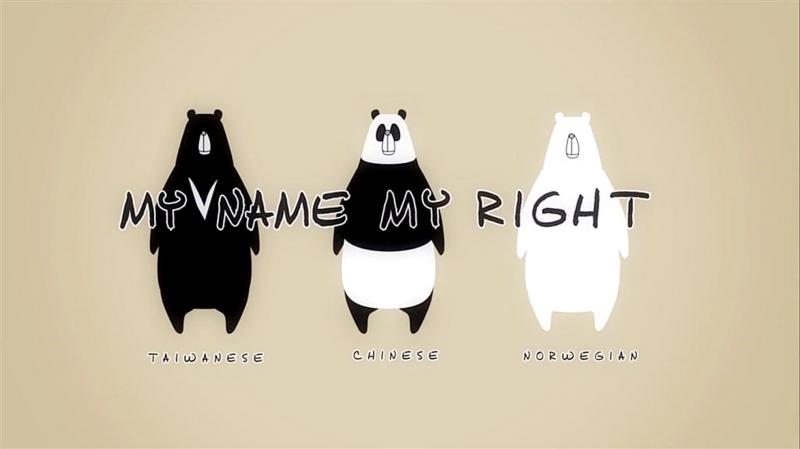

Following a diplomatic row with China in 2010, Norway changed the nationality of its Taiwanese residents to “Chinese.” Liu and others launched the My Name, My Right movement to raise funds and pressure the authorities to change the country designation back to Taiwan. They eventually took the case to the Norwegian supreme court, where they lost in November last year.

While the outcome wasn’t surprising, “we didn’t even have a chance to represent ourselves in court,” Liu says. “The judge just rejected us on grounds that our allegations were unfounded. I’m quite disappointed in Norway’s legal system.”

Photo courtesy of My Name, My Right

Liu and his team filed a lawsuit last month with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in France, where they now have to wait up to a year to see if the case is accepted due to the court’s enormous caseload. As of the end of April, there were about 65,000 pending cases.

If the ECHR rejects the lawsuit, Liu plans to either help Taiwanese in other countries who have similar issues, or bring the issue to the UN.

“It doesn’t matter if we win or not, but we need to keep speaking out,” he says. “If we remain silent, then it will become difficult in the future for Taiwanese to exercise their right to self-determination. Not saying anything means that we’ve quietly accepted the fact of being designated as Chinese.”

Photo courtesy of My Name, My Right

“If this lawsuit wins, it would be the first time for the European Court of Human Rights to make a decision related to national identity,” states a My Name, My Right press release. Since the ECHR is binding on the 47 member states that have signed the European Convention on Human Rights, it means that these countries could no longer register Taiwanese citizens as “Chinese.”

FALTERING TIES

Tensions between Norway and China rose in early 2010 after late Chinese democracy activist Liu Xiaobo (劉曉波) was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Shortly after that, Taiwanese in Norway were forced to identify as “Chinese” to demonstrate the government’s adherence to the one-China principle.

Photo courtesy of My Name, My Right

Taiwan currently has no representative office in Norway — it ceased to operate in 2017 and now all matters go through the office in Sweden.

“It’s really hard for us to make our voices heard,” Liu says. “There used to be a pro-Taiwan group in the parliament, but no longer. We can rally people, but we’re finding it hard to do the same in politics and push them to support some Taiwan-friendly policies.”

For the ECHR battle, Liu has recruited London-based lawyer Schona Jolly, who is chair of the Bar Human Rights Committee and has written about Chinese human rights issues.

Jill Marshall of the Department of Law and Criminology at Royal Holloway College, University of London, said that how a person’s identity is recorded on official documents is a very important matter. It simplifies the complex question of “who we are” into a few words on a document, which may affect people’s rights.

“The applicants are Taiwanese: failing to state this on their official documentation and instead ascribing them with an incorrect nationality misidentifies them and violates their right to personal identity. It is only just and fair that the ECHR acknowledges the violation that has occurred,” said Marshall, who is also the author of Human Rights Law and Personal Identity.”

RAISING TAIWAN’S PROFILE

Liu and his group launched an online fundraising campaign to support their lawsuits, receiving more than NT$3 million.

However, nothing they tried could get through to the courts. They were told that they had no sufficient grounds to their claim due to state policy toward China, and that the designation “would have no consequences and practical significance to their rights and obligations in Norway.”

There are obvious differences, however, as Taiwanese don’t need a visa to get into Norway while Chinese do. There are also different policies toward the two groups due to the vastly different conditions of their home countries.

“Growing up in Taiwan, it was ingrained in us that Taiwan and China are two different entities. China has been threatening Taiwan on all fronts these days, so registering me as “Chinese” is very offensive,” he says.

But Liu feels that popular sentiment has been changing over, as China expands its influence across the globe. When the Liu Xiaobo Incident broke out in 2010, most of Europe was still trying to cozy up to China for economic gain.

“They cast the Taiwan problem aside then because they wanted to be friends with China,” Liu says. “But people are starting to realize the vast differences in ideology and have become wary [of China] ... Technically, there’s little benefit to being nice to Taiwan. But people’s views of Taiwan have changed, especially with the attention it got during the epidemic. Our differences were emphasized in media reports and more people are aware of the problem now.”

Compared to four years ago, Liu has seen an increase in local Norwegians announcing their support for the lawsuit. This is exactly what Liu wants.

“The lawsuit is important. But even more important is that this is an opportunity for more people to know about Taiwan.”

For more information, visit www.facebook.com/TaiwanMyNameMyRight

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

As devices from toys to cars get smarter, gadget makers are grappling with a shortage of memory needed for them to work. Dwindling supplies and soaring costs of Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) that provides space for computers, smartphones and game consoles to run applications or multitask was a hot topic behind the scenes at the annual gadget extravaganza in Las Vegas. Once cheap and plentiful, DRAM — along with memory chips to simply store data — are in short supply because of the demand spikes from AI in everything from data centers to wearable devices. Samsung Electronics last week put out word