June 7 to June 13

If a typhoon was coming in 1898, you’d likely be notified by your friendly neighborhood chief banging on a gong and yelling outside your window. Today, people check their watches and smart gadgets for upcoming storms. But most people who grew up in Taiwan should remember watching longtime weathercasting legend Jen Li-yu (任立渝) in times of severe weather, his low-key calmness a contrast to the howling winds outside.

The 76-year-old Jen made his final weather forecast for TVBS news last Monday, quietly drawing the curtain to a long career.

Photo: Taipei Times screen shot

“Nobody’s paying attention to the weather right now during this outbreak. I’ll take this chance to exit quietly,” he told the media.

Jen, who headed the weather forecasting center at the Central Weather Bureau, made history in 1993 as the nation’s first professional meteorologist to present the weather on the news when he appeared on Taiwan Television (TTV).

“Jen won over audiences with his professional image, and a bidding war broke out among the news channels for other former weather bureau experts,” The Journalist (新新聞) magazine reported in 2005.

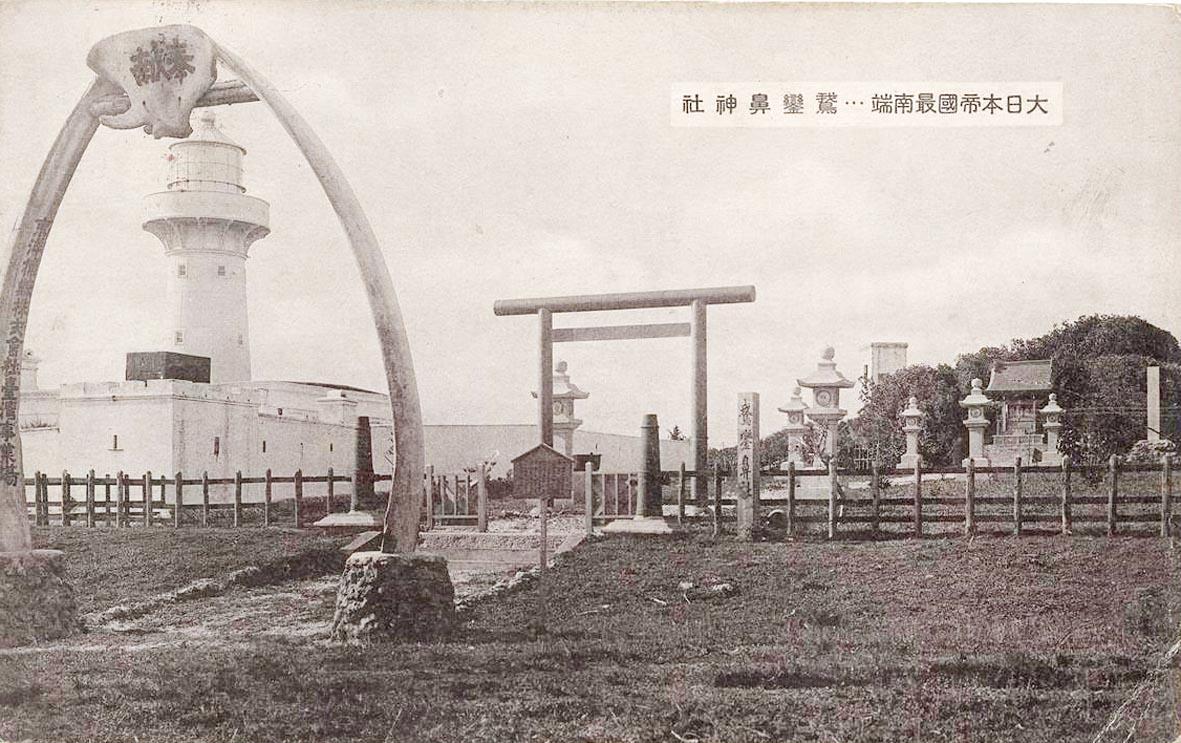

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository

EARLY METEOROLOGY

According to a Hsinchu City Archives Quarterly article, modern weather observation began in Taiwan near the end of the Qing Dynasty. With British guidance, the Qing began building custom houses and lighthouses with basic meteorological technology along its coast. The two it constructed in Taiwan in 1885 (one in Penghu and one in Pingtung’s Eluanbi) functioned for at least a decade.

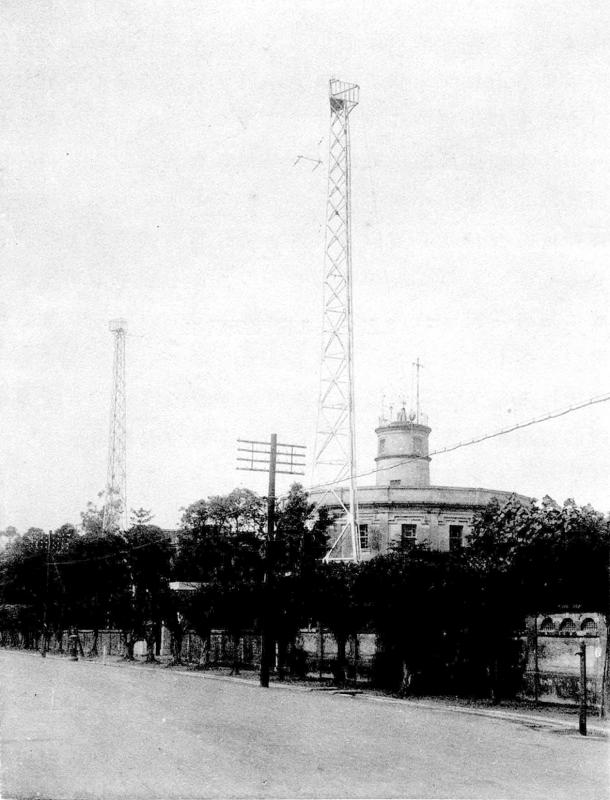

When the Japanese took over in 1895, they immediately launched weather stations in Taipei, Taichung, Tainan and Hengchun, adding Taitung station five years later. All the data was sent to Taipei to be analyzed, and the forecast was published in the newspaper. As Taiwan occupied a strategic position in the crossroads of East and Southeast Asia, this information was also sent to the British in Hong Kong.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The station mapped out its first typhoon in 1897, which ravaged Taipei for over a day. The Tamsui and Keelung rivers flooded, killing over 500 people and destroying more than 17,000 houses. The government realized that just announcing the typhoons was not enough to prevent another disaster, and asked borough and neighborhood wardens to step in and help organize communities so as to mitigate future disasters.

In the next decade, the Japanese built 78 support stations with basic equipment across the nation, completing the nation’s initial meteorological network. More stations were added over the decades, with at least 14 built during World War II for strategic purposes.

The Imperial Japanese Army needed people to operate these new stations, and began training the first crop of Taiwanese meteorologists. One of them, Chiu Ming-teh (邱明德), says in a Formosa TV (民視) history program that training lasted an entire year with little rest as they learned fundamentals like calculus, chemistry and morse code.

Since meteorological data was classified during the war, stations stopped sending out warnings to the villages. In 1942, a devastating typhoon struck the coast of Yilan killing more than 300 people, who had made no preparations, destroying over 11,000 houses. Chiu recalls seeing the damage — trains were tipped over and the train station was obliterated.

The government immediately resumed typhoon warnings to avoid another disaster.

TELLING WEATHER

The Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) meteorology research staff did not follow them to Taiwan in 1949, and the military took over these climate stations. The soldiers were not trained in meteorology and weren’t always accurate — a typhoon alert that was prematurely lifted in 1959 exacerbated one of the worst floods in the nation’s history.

The disaster spurred the government to start training meteorologists, adding the subject as a major in universities.

It was hard to keep up with changes in the weather because each forecast chart was hand-drawn and took up to three hours to complete. In 1963, Taiwan set up its first weather radar stations in Hualien and Kaohsiung with UN funding. They soon could receive satellite charts, which were faxed to the stations and had to be pasted together on a wall.

After a series of deadly storms and floods, the government launched a 10-year program in the late 1970s to revamp the nation’s weather observation capabilities. The 1983 TAIMEX project between Taiwan and the US involving nearly 1,000 officials, meteorologists, academics, students and military personnel from both sides greatly modernized the system. In 1987, the Taiwanese government splurged on a computer, which made Taiwan the first country in the region to digitize weather observation and prediction.

Jen, who was born in 1945, graduated from Chinese Culture University (文化大學) with a degree in atmospheric science. There was no such thing as a weather forecaster back then: the newscaster read data received from the Central Weather Bureau. Jen was used to being on camera though, as he often answered media questions.

The demand for more in-depth weather analysis grew over the years, and in 1993, TTV hired Jen, who had just retired from his post at the bureau. Due to his enormous success, all other channels followed suit, and television history was made. Jen would later work for the other two “big three” channels, China Television (CTV, 中視) and Chinese TV System (CTS, 華視). He finished his career at TVBS.

Jen was known for his reserved demeanor, personable tone and insightful analysis. A TVBS coworker said in a farewell video how Jen hid from the station the fact that he’d had knee replacement surgery and tried to come to work the next day — only to be stopped by his doctor.

Jen was highly regarded even in recent years. A 2017 poll in the paper “TV Weathercasting in Taiwan — a case study on the life cycle of a typhoon” (台灣電視氣象播報研究:一個颱風的生死為例) showed that during times of extreme weather, 42.1 percent of respondents trusted Jen.

After saying his parting words In his farewell video, Jen looks toward the camera and says in his trademark tone: “That’s the weather for today. Thank you, good bye!”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This