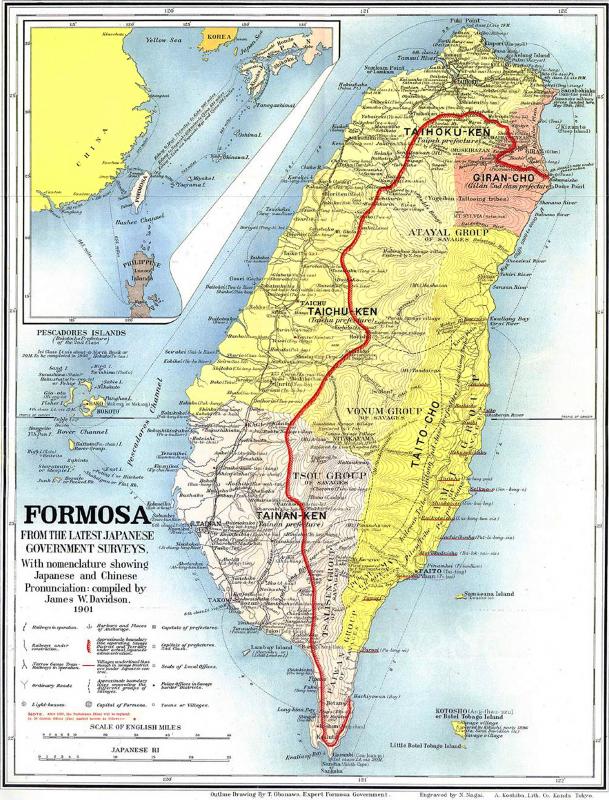

May 3 to May 9

The Japanese soldiers thought they had already subjugated the Atayal when they set out toward the mountains of today’s eastern Taoyuan on May 5, 1907. The two brigades, one from the north and one from the south, were tasked with pushing the colonial government’s frontier defense lines deeper into Aboriginal territory to gain access to valuable camphor.

“The defense lines were used to protect the economic activities, mainly camphor production, on the [Japanese] side of the line,” writes Wu Cheng-hsien (吳政憲) in the paper, “The Principle and Utilization of the Mortars on the Frontier Defense Lines” (近代臺灣隘勇線臼砲之原理與應用). “When the government needed to increase their camphor production, they would repeatedly move the frontier defense line further into the mountains.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Atayal refused to accept these actions. They thought the boundaries had been set when they acknowledged Japanese rule a year earlier. One group ambushed the northern brigade in the south of today’s Sindian District (新店) in New Taipei City, but was quickly defeated. The new border cut through their traditional hunting grounds, and the community lost its land and its ability to resist.

The southern brigade had a much harder time, as they faced a coalition of various Atayal groups and Han Taiwanese rebels. The group with the most at stake was the Bngciq, who had suffered greatly in a prolonged conflict with the Japanese. If the colonizers got their way, the entire Bngciq territory would end up on the government-controlled side of the frontier, putting the other groups under direct threat.

Thus began the Battle of Zhentoushan (枕頭山戰役), a bloody conflict that began on May 5, 1907 and lasted 107 days and required the Japanese to call thousands of reinforcements from central Taiwan to suppress. In the end, Bngciq chief Watan Syat sued for peace, and the Japanese successfully pushed the frontier line deeper by 11km and 15km, making the area one of Taiwan’s most important camphor production zones.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DECADES OF RESISTANCE

The Mkgogan and Msbtunux Atayal (which included the Bngciq) in the area had been resisting colonial forces for two decades by the time of the battle. In 1886, Qing governor Liu Ming-chuan (劉銘傳) attacked the Atayal to protect Han interests in the mountains (and the government’s camphor trade), launching a conflict that would lead to gradual encroachment on Aboriginal territory.

Fighting in the mountains continued for the next five years until the Mkgogan and Msbtunux banded together to resist the Qing in September 1891. This battle lasted for seven months with severe losses on both sides. Although the Atayal eventually lost, their fierce resistance, coupled with increasing numbers of headhunting incidents along the frontier, finally led the Qing to stop their eastward expansion.

Photo courtesy of National Taiwan Library

After the Japanese gained control of Taiwan in 1895, they visited the area, declared the change of government and invited several villagers to visit the governor-general’s office in Taipei. Relations were cordial at first, but conflicts arose again after the government established the Taiwan Camphor Bureau in 1899.

Shizue Fujii writes in the book, The Msbutunux Incident that the Japanese treated the camphor forests as “unclaimed” land, and allowed any licensed Japanese producer to enter without Atayal permission. In 1900, the frontier defense lines were reestablished with armed police following a sharp increase in Atayal attacks.

Under the leadership of Watan Syat, the Bngciq and other groups in June 1900 expelled the Han camphor producers from the mountains and burned the facilities as well as the camphor bureau office. They fended off Japanese retaliation and were able to enjoy a few more years of relative peace.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

However, the Japanese never stopped encroaching on Aboriginal land, pushing the frontier defense line eastward bit by bit and knocking off the Bngciq’s neighboring allies. They came into direct conflict with the Bngciq again in 1904, soundly defeating them in 1906 and forcing them to leave their ancestral land. This scared other Msbtunux groups into surrendering, and camphor production resumed.

FINAL DEFEAT

In March 1907, the government signed a peace agreement with the Atayal. But two months later, they launched an expedition to push back the frontier, igniting the Battle of Zhentoushan. It took the Japanese 41 days to fight their way up the mountain, but reinforcements soon arrived, allowing them to overwhelm the Atayal. The two sides announced a ceasefire on June 23, and met on July 9 to sign a peace agreement. Fujii writes that this is the only existing record of negotiations between the Atayal and Japanese.

The Japanese obtained permission to extend the frontier to Chatianshan (插天山), but agreed to let the village chiefs guide the troops and decide where exactly the line would be. Watan Syat submitted 11 requests, mostly to protect the villagers’ property, interests and safety as well as secure monetary compensation. The Atayal chiefs swore to give up headhunting, and the new frontier defense line was finished on Aug. 20.

The camphor business boomed, but the Atayal soon realized that the Japanese had no intention of keeping their promises. Attacks on the camphor producers resumed until all-out war broke out again in October 1907. This time, the Atayal were crushed within a month, and Watan Syat surrendered to the authorities.

The Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) ran an article, “The regret of the rebel chief,” claiming that Watan Syat was used by Han rebels who wanted to deal a blow to the Japanese without lifting a finger.

“The man who was known for his fierceness finally shed tears and announced his deep regret for his actions,” the report stated.

However, many rebels fled to the other side of the defense line and continued to attack the border guards, and the Japanese responded by cutting off their access to essential goods and bombing their fields during harvest time. Growing desperate with the winter coming, the remaining Msbtunux Atayal crossed the line on Nov. 4, 1908, gave up their guns and swore to “absolutely obey official orders.”

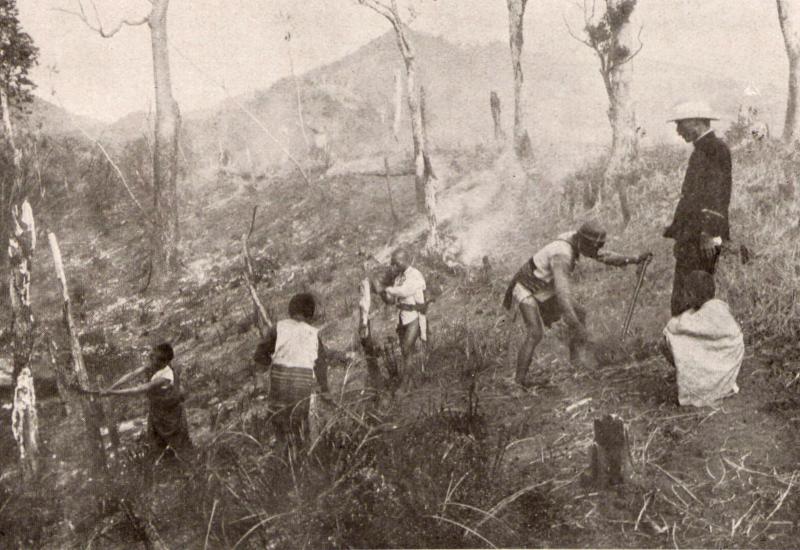

In February 1910, governor-general Samata Sakuma personally visited the frontier to assert Japanese authority. A month later, he brought visiting British diplomats to the area on a boar hunting trip to flaunt the colonial government’s success in “pacifying the savage lands.”

With many hostile Aborigines remaining across Taiwan, Sakuma launched his second five-year plan to “govern the savages” that same year. His forces immediately ran into resistance from the Mkgogan Atayal, who declared war on the Japanese in June. The Japanese expected to finish them off within two months, but the Atayal resisted until Nov. 19, when the last group surrendered their firearms.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades