I arrived in Kaohsiung’s Gangshan District (岡山) hoping to learn about shadow puppetry, and left with a renewed respect for this often-overlooked town.

Kaohsiung Museum of Shadow Puppets (高雄市皮影戲館) is part of Gangshan Cultural Center (岡山文化中心). The museum, which has been revised and repaired since it first opened in 1994, currently occupies part of the first floor. While far from huge, it does provide a decent introduction in Chinese and English.

Taiwanese shadow puppetry, unlike the form of glove puppetry known as budaixi (布袋戲, “cloth bag drama”), is fairly obscure. In the past, shadow-puppet performances were a feature of temple celebrations. Nowadays, the four remaining professional troupes — all based in Kaohsiung, and none having more than seven members — aim to please human audiences with shows inspired by Chinese literary classics.

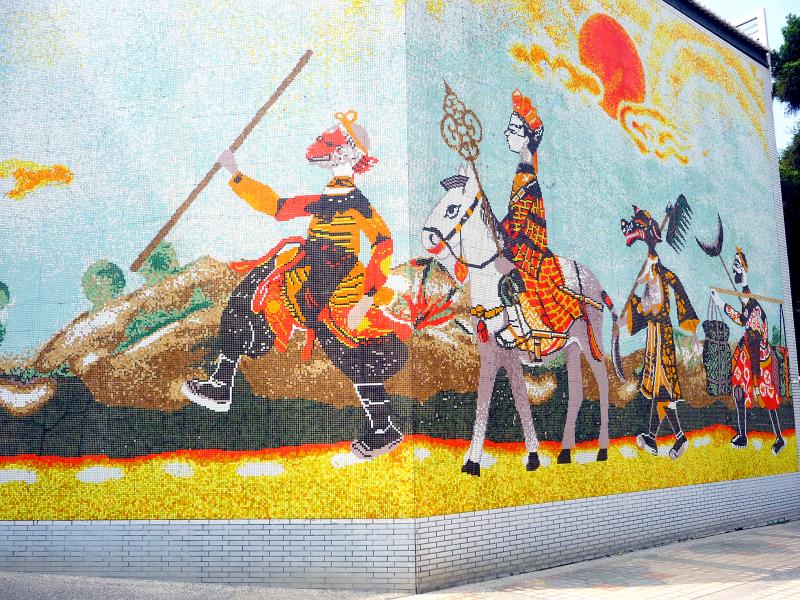

Photo courtesy of the Beitou Museum

SHADOW PUPPETRY

According to a text panel, Chinese shadow puppetry might date from the Han dynasty (202 BCE to 220 AD), the Tang dynasty (618 to 907), or the Song dynasty (960 to 1279).

The golden age of Hoklo-language (also known as Taiwanese) shadow puppetry in Taiwan was the first third of the 20th century, when social stability and economic growth provided opportunities for all sorts of entertainers and cultural workers. However, between the late 1930s and 1945, the colonial government insisted that performers use the Japanese language and adhere to scripts approved by Japanese officials.

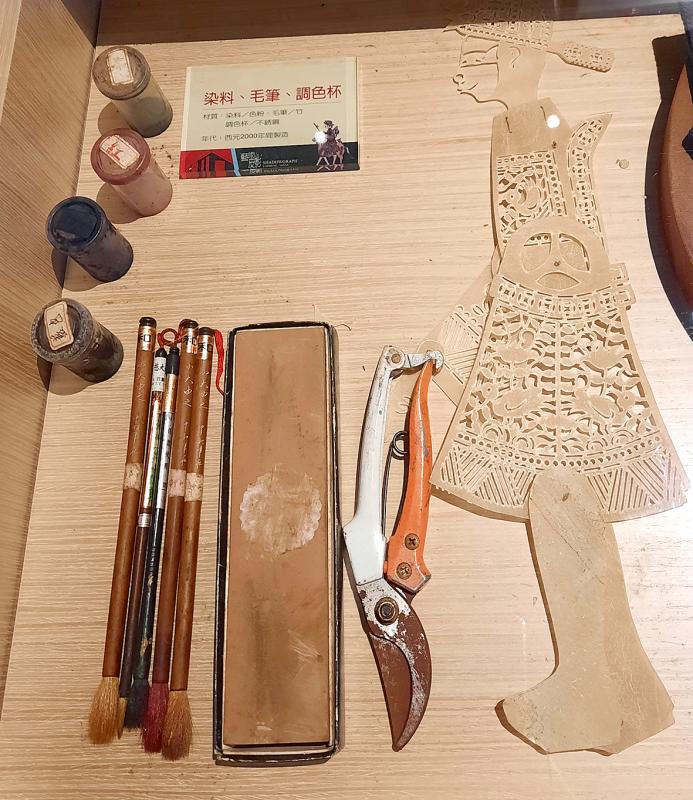

Photo: Steven Crook

One section of the museum explains how shadow puppets are made. The preferred materials are buffalo hide, donkey skin and sheep skin. Translucency is essential, so the skins are thoroughly washed and bleached before carving.

Shadow play isn’t a monochromatic medium. Dyeing the leather (usually red or green) is the final stage before the addition of jointed, moving parts such as the head and limbs.

The museum displays several beautifully-crafted puppets. Unfortunately, visitors aren’t allowed to take photographs of most of them.

Photo: Steven Crook

In addition to humans and deities, animals appear in some stories. I sat and watched a videotaped performance in which a rooster battled with a huge worm, ate it, and then got chased by a cat.

As in the various types of opera that emerged in China and Taiwan, human characters are divided into four categories: sheng (生, strong and righteous men), dan (旦, females), jing (淨, rogues) and chou (丑, buffoons and jesters).

Puppets may still be made the age-old way, but lighting technology has made great progress. During the period of Japanese colonial rule, gas lamps replaced oil lamps. They in turn gave way to tungsten bulbs and eventually LEDs.

Photo: Steven Crook

Kaohsiung Museum of Shadow Puppets is open from 9am to 5pm Tuesday to Sunday. Admission is free. For more information, visit (Chinese and English): kmsp.khcc.gov.tw.

GANGSHAN OLD STREET

During the short bike ride from the museum to Gangshan Old Street (岡山老街), I passed construction teams extending Kaohsiung Metro’s Red Line.

Photo: Steven Crook

Unlike several other “old streets” around the country, the section of Pinghe Road (平和路) that boasts several pre-1945 buildings hasn’t been tidied or restored at the behest of the authorities. Even so, architecture fans with a bit of persistence will find several pearls in the rough.

The most obvious of these is no 50. If you ignore the first floor — a closed-down cram school — this three-story, three-shopfronts brick-and-concrete edifice may make you think of old synagogues in Eastern Europe.

No 79 used to be a drugstore. Red script under the second-floor balcony shows its Chinese name, Taiji “Western” Pharmacy (太吉西藥房). Higher up on the corner of the building, the English words “Good Luck Dispensary” are still visible.

Photo: Steven Crook

The ex-pharmacy likely dates from the 1920s. The third floor was probably added sometime before 1980, judging by its appearance.

Nos 82 and 84 comprise a colonial-era facade grafted onto what must be a Qing-era structure made of mudbricks and tiles.

Zigzagging through nearby alleyways, I found myself on Weijen Road (維仁路), Gangshan’s main commercial thoroughfare until the arrival of the north-south railway shifted the town’s center of gravity to the east. These days, it looks like an excellent place to find a cheap lunch.

Photo: Huang Chia-lin

Datong Lane (大同巷) is much quieter. Turning around to take another look at a appealing single-story traditional house, I noticed a sign that offered a very particular service.

SOOTHING A SHOCKED SOUL

Variously translated as “soothing a shocked soul” or “reconstituting a soul shattered by fright,” shoujing (收驚) is a folk ritual through which a practitioner attempts to assuage a traumatized personality. In the past, if you were sure you’d seen a ghost, you’d likely undergo shoujing. More recently, I’ve heard of it being sought as a remedy for jet lag that just won’t go away.

Curiosity got the better of me, so I walked down the alley and spotted three women in one wing of the traditional house. They were sitting and talking; I couldn’t tell if the ritual was about to begin, already underway, or all over. I did notice another sign, saying that shoujing was available from 9am to 5pm, Monday through Friday, except for lunchtimes.

The Japanese, who took a dim view of Taiwanese folk practices, left their mark on Gangshan in the form of practical, prosaic infrastructure.

The 31m-high Old Gangshan Water Tower (岡山舊水塔) at 450 Gangshan Road (岡山路) dates from 1937. It played a role in the town’s water supply until 1992. It’s come through quite a few earthquakes and typhoons almost unscathed.

The tower was selected as one of Taiwan’s Hundred Scenic Historic Buildings (臺灣歷史建築百景) in 2001 through a mix of public voting and expert assessment, in a process overseen by the Council for Cultural Affairs, the predecessor of the current Ministry of Culture.

No part of the property, which appears to cover the better part of a hectare, is open to the public. What with its dozens of mature trees and pre-1960 buildings, the site could be turned into a very nice park. Let’s hope that’s what eventually happens.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of ‘Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide’ and co-author of ‘A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai’.

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,