April 5 to April 11

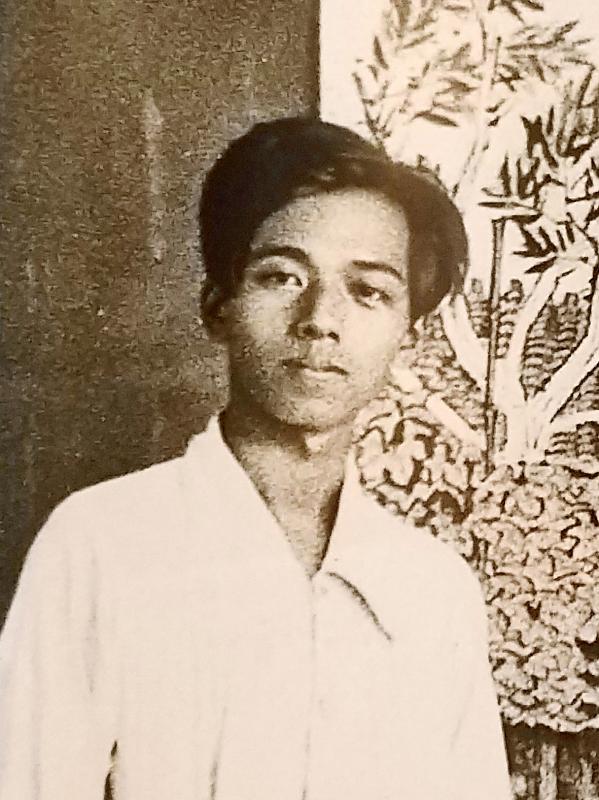

During the final months of his life, Kuo Hsueh-hu (郭雪湖) repeatedly asked his children to bring him down the mountain back to Fanzaigou (蕃仔溝), where he was born on April 10, 1908.

The centenarian had been living near San Francisco for decades, but as his condition worsened he began to think that he was on Guanyinshan (觀音山), which overlooks his childhood stomping grounds along the Tamsui river.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Kuo is one of Taiwan’s best-known painters, bursting onto the scene in at the age of 19 as one of the “Three Youths of the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition” (台展三少年) along with Chen Chin (陳進, Taiwan’s first female commercial painter) and Lin Yu-shan (林玉山).

Difficulties under both the Japanese and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regimes led Kuo to spend much of his adult life overseas, first heading to China in 1941 after World War II made it hard for him to make a living as an artist in Taiwan. He returned to Taiwan after the war, but left again in 1964 for Japan and finally the US, which became his primary residence until his death in 2012.

In 1987, Kuo returned to Taiwan for the first time in 23 years, reuniting with Chen and Lin to commemorate the 60th anniversary of their Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition debuts with an exhibition at Taipei’s East Gallery (東之畫廊). He spent the next 10 years flying back and forth the Pacific Ocean until Chen died in 1998 and he himself couldn’t withstand long-distance flights anymore.

Photo: CNA

Despite Kuo’s fame, not much was known about his later personal life until his son Kuo Song-nian (郭松年) published his biography, Home Gazing (望鄉) in 2018.

“Like our father, the rest of the Kuo family is also fated to live a life of separation and wandering,” the younger Kuo writes in the foreword. “But for him, I turned into a junk ship with its sails fully unfurled, returning to the foot of Guanyinshan to pick up the pebbles on the shore than contain his memories.”

EARLY FAME

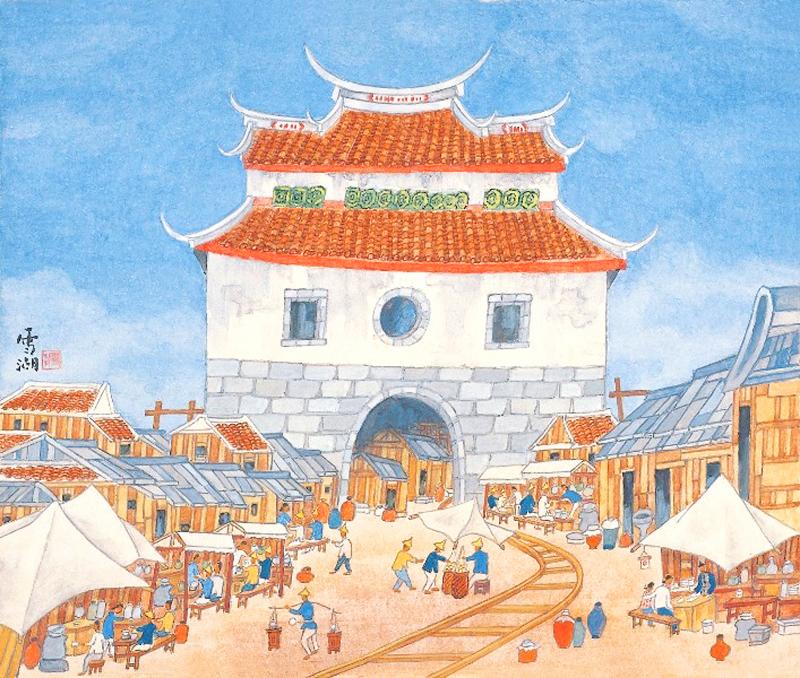

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Unlike many of his peers, Kuo’s family was of modest means and was unable to send him to Japan to further his artistic studies. Instead, he made it into a very competitive technical school at the age of 15 to study drafting.

Kuo’s teacher and relatives were furious when he quit just after a semester, telling him he was throwing away his future. But his mother Chen Shun (陳順) supported his decision and let him develop his painting skills at home. One day, Chen secretly brought one of Kuo’s pieces to renowned painter Tsai Hsueh-hsi (蔡雪溪) to ask if her son had any hope of success in the field.

Tsai was impressed and took Kuo as his disciple, giving him the artist name Hsueh-hu, which means “snowy lake.” Kuo used this name for the rest of his life. He mostly painted religious figures under Tsai, and also learned how to frame paintings — which became his main income source after he left Tsai’s studio.

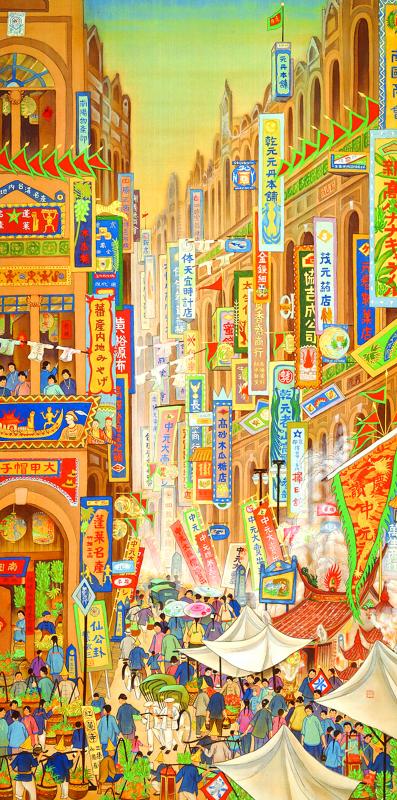

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In 1927, the Japanese government launched the inaugural Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition, garnering hundreds of submissions. When the final list was revealed, the artist community was shocked to find that out of all the Taiwanese artists, only three unknown 19-year-olds made the cut. Kuo was the youngest of the trio, and his Waterfall in the Pine Valley (松壑飛泉), which combined traditional Chinese and modern techniques, drew much attention.

Kuo completely abandoned traditional painting shortly afterwards, shifting his focus to Eastern gouache landscapes. He spent nearly six months working on his submission for the following year: Scenery Near Yuanshan (圓山附近). His mother borrowed money and even sold her jewelry to support his endeavor, but Kuo was able to pay everything back as the Governor General’s office purchased the piece for a hefty sum.

LIFE OF WANDERING

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Soka Association

In 1931, a 23-year-old Kuo traveled abroad for the first time, touring art studios and exhibitions in Japan. He had his first solo show two years later, and his career blossomed.

Fine art exhibitions continued in Taiwan after World War II broke out, but it became increasingly harder for artists to make money. Now with a family to raise, Kuo headed to China.

His mother carefully watched over his paintings back home, and when the Allies bombed Taipei in 1945, she dashed into the rubble to save his work. Kuo was stuck in Hong Kong for months after World War II, finally returning home in early 1946.

Photo: CNA

Kuo gave his all to building up Taiwan’s art scene, but unfortunately the KMT favored traditional Chinese art and questioned the legitimacy of the Japanese-influenced Taiwanese painters. This debate raged on for years, and at an art forum in 1954, Kuo stressed that art should transcend national boundaries and focus on creation and developing new styles. His opposition to the government’s stance only worsened his situation.

The family’s finances hit rock bottom in the early 1960s, and in 1964, a disillusioned Kuo moved his family to Japan.

Things changed again when Kuo’s eldest son Song-fen (松棻) became heavily involved in the baodiao (保釣, “protecting the Diaoyutais”) student movement while studying in the US. The leftist-leanings of some of these groups led to several students — including Song-fen — being blacklisted as “communist bandit agents” by the KMT.

Photo: CNA

Kuo worried that his son’s blacklisting would cause his family problems. He no longer found Japan safe, especially after they deported a Taiwanese independence activist a few years earlier. The family moved again, joining Song-fen in California.

Over the years, Kuo traveled extensively, but he didn’t exhibit again until 1979 when he was invited to Beijing. Interestingly, the Chinese loved his art, which was dismissed as not being Chinese enough in Taiwan.

In 1987, an anxious and excited Kuo landed in Taipei. Everything had changed, but he was pleased to see that the city had its own fine arts museum and tons of galleries. He reunited with Chen and Lin, who were both still going strong.

Chen Chin joked, “They called us ‘Three Youths’ when we were young, and even though now we’re old, we’re still the ‘Three Youths.’”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she