Taiwan became the world leader in Chinese-language pop music in the 1980s, but two decades earlier, the country was already leading Asia in a very different aspect of the music industry –– pirated vinyl records.

In 1965, more than 45 factories, most of them in what is today’s Sanchong District (三重) in New Taipei City, churned out around 350,000 pirated records a month, everything from the Beatles to Hong Kong’s latest pop stars.

This reign of piracy continued until the advent of US copyright sanctions in the early 1990s, and along the way helped power the soundtrack to the Vietnam War in Asia. Records flowed out of shops located just outside of US military bases in Taipei, Taichung and Kaohsiung, then diffused to US outposts throughout Asia –– to Vietnam, Japan, Korea, Thailand and the Philippines.

Exports of Taiwan bootlegs, via both US military and other channels, were then estimated in excess of 150,000 records a month. One smuggler was caught en route to Hong Kong with over 900 Taiwanese bootleg records in a suitcase. The scale and reach of the industry makes one wonder, when Martin Sheen’s character in Apocalypse Now sails up the river to find Colonel Kurtz, is Kurtz listening to Taiwanese bootleg vinyl?

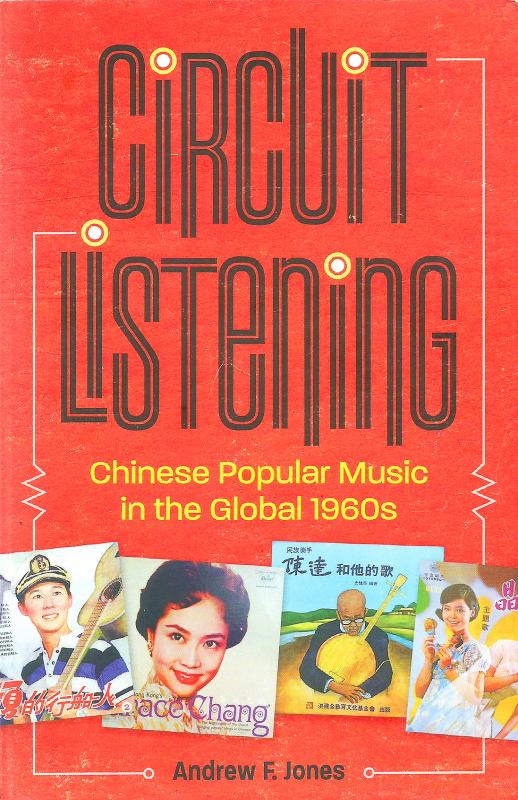

Pirate records and other Asian music distribution networks are the subject of a fascinating new book, Circuit Listening: Chinese Popular Music in the Global 1960s by Andrew Jones, a University of California at Berkeley professor of Chinese.

Jones’ history traces Chinese pop music from the 1950s to the 1980s, looking at defining songs and singers –– including Mandopop divas Grace Chang (葛蘭) and Teresa Teng (鄧麗君), the first great Taiwanese pop crooner Wen Hsia (文夏), the blind moon lute-playing icon of traditional music Chen Da (陳達) and the Maoist anthem The East is Red (東方紅) — through the lens of the technologies and listening cultures which allowed their mass circulation and popularity. It also charts a very interesting fusion of Chinese and Western pop music styles over the course of the 20th century.

Jones argues that this history of this musical miscegenation was largely determined by “circuits,” a metaphor he applies to both the geographical networks by which music traveled via land, sea and air, and also the miniature electronic circuits of cheap consumer technologies, which from the 1960s onwards flooded Cold War market economies with transistor radios, tape recorders, and other portable listening technologies.

It is also worth mentioning that though this is a history of “Chinese popular music,” the greater part of the book focuses on Taiwan’s music industry, which became the dominant producer of Mandarin and Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) pop songs after World War II.

‘MIXEd BLOOD SONGS’

The roots of Chinese recording industries, however, stretch back to the Japanese colonial era. By the late 19th century, a maritime circuit ran from the Western US through Honolulu to Asia’s major ports of Yokohama, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Manila and Singapore. The trade in musical information occurred via sheet music, traveling musicians, and a few 78rpm shellac records, which could hold a maximum of about four minutes per side.

The effects were first felt in 1930s Shanghai, where the Chinese “modern song” emerged as a fusion of existing Chinese styles and Western pop jazz. Later, in the 1950s, the Hawaiian steel guitar came to be a defining element in the music by the great early star of Hoklo pop, Wen Hsia.

Also in the 1950s, an evolving global network brought Latin rhythms to Asia –– sambas, rumbas, mambo and calypso –– and these began to infect the music of Chinese pop stars of the 1950s and 60s, most notably Grace Chang.

Chang, born in Nanjing as the daughter of a Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) government official, shot to fame in post-World War II Hong Kong. She is the voice behind one of the most iconic musical remnants of her era, I Want Your Love (我要你的愛), which recently featured in the wedding scene of the film Crazy Rich Asians. The song itself is known as a “mixed blood song” (混血歌), a remake of a Western song with Chinese lyrics. In this case it’s based on an American jump blues number, I Want You To Be My Baby first recorded in 1953 by Louis Jordan.

Chang’s repertoire stretched from Chinese opera to Western pop, and Jones argues that singing in Mandarin (rather than Cantonese, like other Hong Kong singers), helped her first become a regional star among the Chinese diaspora throughout Southeast Asia, and then even take a stab at the West.

On opposite sides of the Pacific, however, Chang was viewed quite differently. To Chinese media, she was “the mambo girl,” an emblem of a new Westernized (or globalized) generation. When she appeared on American TV on The Dinah Shore Show in 1959, she was introduced as “an archetypically ‘Chinese’ singer.”

MUSICAL ‘CIRCUITS’

For Jones, the interest here is in the communications networks and technologies that brought about this cultural mixing. Early on, he invokes Marshall MacLuhan’s famous dictum, “the medium is the message,” and he plainly states that he prefers to analyze Mao Zedong (毛澤東) as a kind of “media effect” and Teresa Teng “not so much as a historical personage,” but rather “as a kind of domestic appliance.”

This leads to some very interesting results. Taiwan’s pirate record industry, for example, eventually converted its industrial capacity to legitimate manufacturing, while some companies went on to open music studios and produce original music.

Taiwan’s record pirates openly branded their records, and among the pack, First Records (第一唱片) was known for the best quality. The company’s founder, Yeh Ching-tai (葉進泰) went on to open Taiwan’s first multi-track recording studio in 1981, and then in 1988, he established a world-leading brand for the manufacture of CDs, DVDs and other optical media, Ritek (錸德科技).

Other parallels abound. The same year that a nine-year-old Teresa Teng began joining singing competitions, 1962, Taiwan’s electronics industry found its start in a Japanese joint venture called National Panasonic in New Taipei City’s Jhonghe District (中和). By 1968, when Teng had just started releasing records, electronic goods were Taiwan’s second largest export. By the 1970s, Teng’s songs infiltrated China via cassettes and radio, and applied soft culture pressure towards China’s eventual “reform and opening-up.”

Jones presents all this and much more through his wonderful histories of musical “circuits.” The book is packed with exacting research and close textual decodings of music and films. Around 50-pages of footnotes reference a who’s who of Taiwanese pop culture critics and scholars among the many citations. Though the book bears an academic imprint, it is easy reading and largely jargon-free. If you’re looking for a sentimental biography of Teresa Teng, it may not be for you. But for Chinese music nerds, Circuit Listening is an absolute must-have.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality