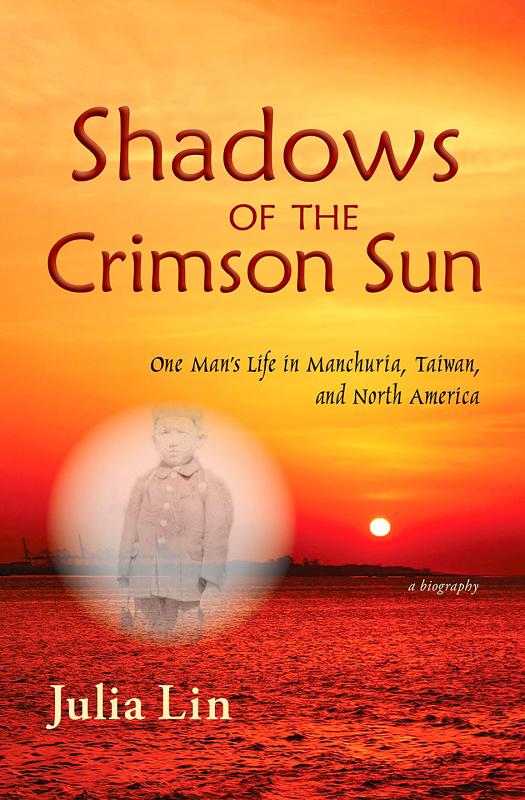

I’m informed that it’s taken for granted by writers that there are too many memoirs — the market’s saturated and they’re as a result unpublishable. Julia Lin’s Shadows of the Crimson Sun is part-memoir but also part-novel. In addition, it was published over three years ago, and by a small, independent Canadian publisher.

It tells of the life of Charles Yang, who was born Yang Cheng-chau, and his migration from the former Japanese puppet-state of Manchuria back to Taiwan, and thence to North America.

Born in Taiwan in 1932, his family moved to Manchuria two years later. He left to return to Taiwan aged 14 following the defeat of Japan in World War II and Manchuria’s invasion by the Soviet Union. Around 5,000 elite Taiwanese made their homes in Japanese Manchuria between 1931 and 1945, adopting Japanese names. Charles’s father was one of them, settling in what is now China’s Shenyang, Liaoning Province.

In saying this book is part-novel I don’t mean to imply that anything is invented. Rather, it’s the style that is quasi-fictional, the presentation of a real-life story without the paraphernalia of too many notes. A great vividness is thereby attained, not least about Taiwan under Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule, and then life and radical activism in Canada (calling for political reform in Taiwan) by one of the early Taiwanese-Canadians to settle in Vancouver.

The detail is extraordinary. No other book I know has made Japanese Manchuria spring to life in the way Julia Lin (who was born in Taiwan) does here, with the Japanese-Russian hostility in the region especially vividly presented. And she proceeds to exhibit a similarly extensive command of life in the periods relevant to her story in Taiwan, the US and western Canada. The result is an enthralling narrative featuring Taiwan and some of the many places that Taiwanese have migrated to.

It’s tempting to linger over this book’s riveting Manchurian chapters, but readers will be keen to know what happens when Charles Yang gets to Taiwan, and later North America, so we must move on.

Yang stayed in Taiwan from 1946 to 1959, enrolling at the Tainan First High School, his father’s alma mater. Taiwan was then a place of paradoxes. On the one hand it enjoyed one of the highest standards of living in East Asia, while on the other women could still be seen hobbling around with bound feet. But above all, it was experiencing the White Terror, the KMT’s way of repressing opposition. The usual items are gone through: the 228 Incident (far more than an “incident”), political trials, imprisonment on Green Island and so on. Lin quotes an estimate of summary executions during this period as being as high as 45,000.

In Manchuria, Yang had felt inferior for not being Japanese. Now in Taiwan he felt similarly for not being a Mainlander, or those who fled to Taiwan with the KMT following its defeat in the Chinese Civil War. Nevertheless, by 1951 he was enrolled at Taipei’s National Taiwan University as a medical student, on a seven-year program. There he became a Christian and, in 1957, married Wang Ai-chen, or “Jane” (also from Manchuria), in a Christian ceremony.

Then, in 1959, Yang took a flight, via Midway, Guam and Hawaii, to San Francisco, to take up an offer of an internship in Chicago, to be followed by one in Detroit. The Taiwanese government only allowed emigration after candidates had completed their military service, but Yang had been exempted on account of his severe myopia. Jane initially stayed in Taipei, but joined her husband in 1962 after he had accumulated enough funds to satisfy the US immigration requirements. The Yangs now had to start a new life, and to learn English.

The couple also began to develop feelings for Taiwanese independence, and anger at the injustices of KMT rule. The radicalism that was engulfing the US in the 1960s only served to fuel these sentiments. But then Charles Yang’s US visa expired. He responded by moving to Canada, becoming one of the first Taiwanese immigrants to Vancouver.

He also became a more serious political radical. In 1970, there was an attempt to assassinate Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), at the time Taiwan’s vice-premier, when he was on a state visit to the US. Charles Yang contributed a month’s salary to the would-be assassin’s defense fund, and appeared on TV in Seattle to defend the protest movement. This was a risky move. Defiance, even in far-away Canada, could result in jail, torture and even murder of family members back home in Taiwan. But Charles’s immediate family were all now in North America. He did try, twice, to re-visit Taiwan but was luckily denied the necessary documents. Others in his position had gone but had never returned.

In British Columbia life was not without its problems. The Canadian province had a history of anti-Chinese racism, though measures to reverse this were to begin in the 2000s. But even some Taiwanese immigrants retained language-based prejudice, such as that of Hokkien-speakers vis-a-vis the others. Differences between immigrants from Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia only added to the mix. Yang responded by becoming active in the Vancouver Taiwanese Presbyterian Church.

Charles’s wife died in 2010. Vancouver remained one of the world’s most desirable cities to live in. Over 100,000 Taiwanese have gained Canadian citizenship, with the largest community living in Vancouver. Moreover, the 2014 Sunflower protest movement gave Charles new hope for Taiwan’s future.

The book’s last chapter is a depressing account of the afflictions of old age as experienced by Yang. Doctors aren’t exempt from the shocks that flesh is heir to, after all.

It seems to me extraordinary that this book, on sale at a very cheap price (under three US dollars), both in Kindle and paperback format, isn’t better known. It’s both authoritative — the author spent three years on her research — and gripping. Clearly Charles Yang provided a wealth of personal information, but Julia Lin has in addition researched her background with enormous thoroughness, making this a book I will long return to and remember.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.