Jan.4 to Jan.10

Writer Sanmao (三毛) didn’t spend much time in the mountain village of Chingchuan (清泉) in Wufeng Township (五峰), Hsinchu County, something about the place seemed to deeply impact her heart.

“When I think of Chingchuan, it’s as if there’s a kind of pain,” she wrote to Father Barry Martinson, the Jesuit priest in Chingchuan who invited her to visit. “It’s not tortuous, yet it hurts so much. Whenever something too wonderful enters my life, I always feel pain and loneliness. Of course, there’s joy mixed in as well, but not much.”

Photo: CNA

That was after her third trip there in February 1984, six years after her life in the Sahara Desert and the Canary Islands came to a close with the accidental death of her husband Jose Maria Quero y Ruiz . The late writer, who committed suicide in Taipei on Jan. 4, 1991 (some dispute the cause of death) gained widespread fame for her writings on her adventures abroad, but Chingchuan is one place in Taiwan that she’s still closely associated with.

“After I started living alone, I realized that my loneliness grew by day. The friends from Chingchuan visit me in my dreams almost every night, and these people’s faces make my heart ache,” she continued in the letter.

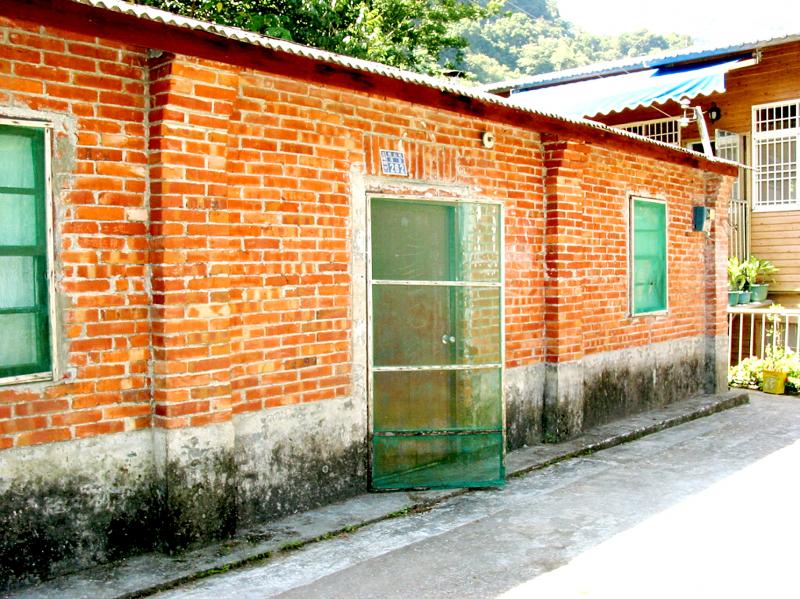

The red-brick residence Sanmao stayed at in Chingchuan has been converted into a museum-cafe-shrine, and is one of the main draws to the mostly-Atayal village where Martinson still resides as the local priest.

Photo: Tsai Meng-shang, Taipei Times

“Chingchuan is beautiful. Chingchuan is real... Please beg for God to take away the confusion and sorrow in my heart,” she wrote.

JOURNEYS ABROAD

Sanmao (real name Chen Ping, 陳平) first met Martinson on Orchid Island in 1972. She had just returned to Taiwan after studying in Europe and the US, where she traveled extensively. They had promised to meet up again in Taipei, but Martinson left the paper with her address in a cab and couldn’t find her house on the day of the meeting. He called her home, but his Chinese wasn’t good enough then to explain to her father what he wanted, and the two lost contact.

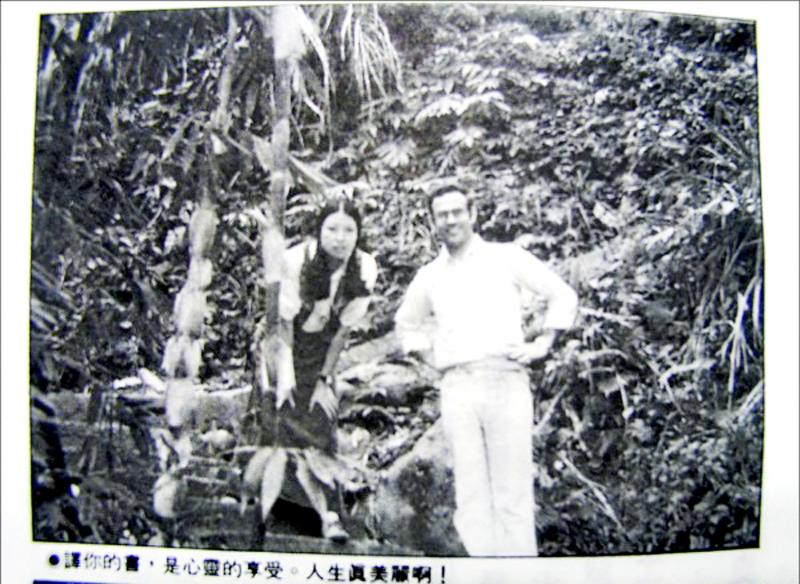

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Sanmao suffered several heartbreaks during this time, including the death of a fiance, and decided that she couldn’t stay in Taiwan anymore after a failed suicide attempt. In March 1973, she set out for Spain again, where she rekindled her friendship with Jose, whom she had first met in school in 1967. They got married and settled in today’s Western Sahara, where she began writing to great acclaim about their life for the United Daily News literary supplement. These stories were included in five collections of essays.

Jose died in a diving accident when Sanmao was visiting family in Taiwan, and the devastated writer returned to Taiwan where she was treated as a literary superstar. She lamented in an 1980 speech: “After I came back, I found that my name had been forcefully changed. My real name is Chen Ping, but now it’s become Sanmao … Sanmao represents those five books, but I represent myself, those are different matters.”

The pressure was such that she sought refuge in the Canary Islands in 1980, writing to her parents: “Human beings are lonely creatures, and I’m just as lonely in Taipei. People know Sanmao, but they don’t know me.” However, she still returned home in 1981 as a special guest for the Golden Bell Awards, after which she began teaching writing to college students and producing her own work.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Under the sponsorship of the United Daily News, she traveled to 12 countries in Central and South America, publishing a book and giving talks across Taiwan about her experiences.

DISCOVERING THE HOUSE

Ten years after their missed connection, Sanmao and Martinson got back in touch. In 1982, Sanmao visited Martinson in Chingchuan for the first time and translated his first book, Song of Orchid Island, into Chinese so it could be published.

Photo: Liao Hsueh-ju, Taipei Times

Despite Sanmao’s itinerant life, she was deeply drawn to Chingchuan. She visited for the third time in 1984, when the villagers held a big welcome party for her at the church. The next day, Sanmao, Martinson and a few young villagers walked across the drawbridge where an old and derelict red-brick house caught her attention.

She writes in an essay published in the United Daily News that she froze in her tracks. “This is another climax of my life of scavenging; I know what kind of treasure I had stumbled upon, and my heart started pounding.”

Martinson writes that the house was full of trash, the walls were crooked and the roof was porous. But Sanmao was certain that this was her “dream house.” She quickly drew up plans for the house, and Martinson managed to convince the owner to rent it to her for three years. She wrote to Martinson about the house, comparing it to the place where the Little Prince met the fox every day.

“The Little Prince sobbingly told me that he could no longer return to the Sahara,” Sanmao wrote. “He needs a place, where his planet is right above him, where he can rest alone and not miss home.”

However, Sanmao had become ill and mentally strained with overwork, and didn’t get to see the house before she left for surgery in the US. In May 1984, she announced in the United Daily News her intentions to open the house to young people in Taiwan:

“I welcome everyone to enjoy the Little Prince’s starry sky; those who desire to return to nature can use this house that I couldn’t even stay in for one day,” she wrote. She urged people not to use it just for tourism and for them to respect the environment and local Atayal culture with a pure heart, and to help out the locals if they could.

Martinson writes he received numerous calls asking about the house, and countless people from across Taiwan passed through due to Sanmao’s calling. Sanmao finally visited the house in the summer of 1985, before heading abroad again. That was her last visit.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful