When it was first suggested to Yuval Noah Harari that he appear as a character in the illustrated version of Sapiens, his mega-bestselling “brief history of humankind,” which is about to be published in graphic form, he did not jump at the idea.

“I vetoed it,” he says over the phone from his home outside Tel Aviv. “I try to keep myself mostly outside my books.”

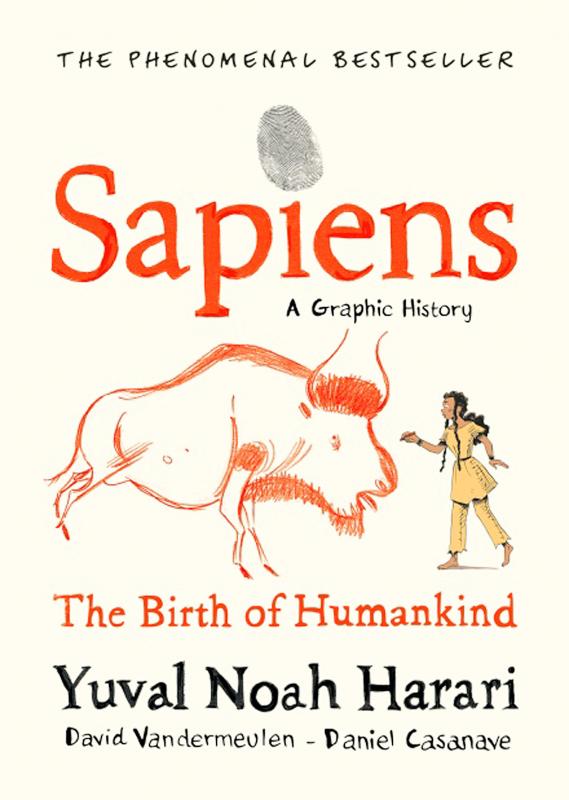

Sapiens covers the broad arc of our species’ story, from the emergence of human cultures in Africa 70,000 years ago to our hyper-connected present, in 500 pages. It has been one of the most spectacular publishing successes of the past decade, selling more than 10 million copies since it was translated into English in 2014, and its enormous popularity has turned a little-known Israeli history professor into one of the most influential public intellectuals on the planet.

But for all his ambition and influence, Harari cuts a rather sober figure. Slim, bespectacled and shaven-headed, he speaks softly but insistently not just about our distant past but also of the near future of humanity and the various existential threats looming.

“If Harari weren’t always out in public,” a New Yorker profile noted earlier this year, “one might mistake him for a recluse.”

So it’s curious to see the 44-year-old appearing in Sapiens: A Graphic History, serving as an avuncular cartoon tour guide through the early days of humanity. On the opening page he greets us from an armchair, book open on his lap, ready for story-time; later he leads a fictional niece through the complexities of evolution and his theories on how an obscure savannah-dwelling ape rose to world domination.

His co-authors on the new book, the French illustrator Daniel Casanave and Belgian scriptwriter David Vandermeulen, insisted Harari step into the frame.

“They convinced me it’s a very efficient storytelling technique, and that it would make it easier to convey at least some of the messages if you have this guide who accompanies the reader,” Harari says.

As a compromise, they agreed to include a cast of scientists “who could explain different disciplines and present different theories — it’s important to show science as a collaborative effort and not as an individual enterprise,” Harari says.

Some, such as the Oxford anthropologist Robin Dunbar, a specialist in primate behavior, are real figures who have shaped Harari’s thinking; but most are fictional. Among the cast are a masked superhero, Doctor Fiction, who personifies “the human superpower to create and believe in fictional stories”, and a hard-boiled New York detective “investigating who killed most of the big animals of the planet more than 10,000 years ago”. (Spoiler: it was us.)

Sapiens grew out of an undergraduate lecture series on world history at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where Harari still teaches, before becoming a bestseller in Israel in 2011.

“The core ideas have remained the same” with each new adaptation, says Harari, though the illustrated version did give him “the opportunity to rethink some of the details — science has discovered a lot of new things over the past decade and a half.”

It also challenged Harari to flesh out some of his original observations.

“Texts can be very abstract, but when you draw, you have to be concrete,” he says. “So, for example, if you discuss sexual relations between Sapiens and Neanderthals, in a text you can avoid the question of, was it a Sapiens man with a Neanderthal woman or the other way around? What did they look like? It forces you to go back to the scientific research. And of course, it brings up a lot of issues, ideological and political, about race and gender. Even if you don’t have all the facts, you need to make a call. Some of the liveliest debates that we had were exactly about such issues.”

Sapiens has already reached tens of millions of readers across nearly 50 languages. Now, in addition to the illustrated version, which will unfold over four volumes, Harari — who last year founded a social-impact company called Sapienship with his husband and agent-manager Itzik Yahav — is planning a history of the world for younger children; there is also talk of a TV adaptation of Sapiens and a touring exhibit. What is it about the book’s message that he feels is so urgent to get to an even wider audience?

“I think it answers a crucial need,” he says. “Because we live in a global world, you need a big-picture understanding of history now to really understand your own life. Most educational systems basically just teach you the history of your country, your religion, your culture. I went through 12 years in Israeli schools and never heard a thing about the history of China, or about anything prior to Judaism. I don’t think I had a single lesson about the agricultural revolution. So people need this big picture, and Sapiens provides it in a way which we tried very hard to make accessible and interesting and fun.”

Accessibility is key here.

“When you look at what’s happening now in the world with COVID-19, and all the conspiracy theories, you see the importance of science reaching not just a small elite, but everybody,” he says. “One big handicap is that science is usually much more complicated than the conspiracy theories, and scientists often speak in jargon and numbers and statistics and graphs, which most people find difficult — people usually think in stories.”

In the graphic version, “we remain faithful to the core scientific facts and theories, but we can experiment with new ways of telling the story, and thereby reach a wider audience.”

Harari is aware that the success of his books has led some people to view him as a prophet, which makes him uneasy.

“I keep saying, ‘I don’t know what’s going to happen.’ The whole point of writing books is to try to change the future, not to predict it.”

However, he admits he feels fearful about what lies ahead.

“In the long span of history, the Black Death and the influenza of 1918-19 were much worse. [COVID-19] is a relatively mild epidemic in terms of mortality. Its most dangerous potential is its impact on our ability to deal with other threats. Nuclear war, ecological collapse and the rise of disruptive technologies like AI — these three threats can really destroy human civilization if we don’t handle them correctly. And all three demand global cooperation to deal with them. If we react in the wrong way to the present crisis, it will destroy whatever remains of global cooperation; it will create a poor, violent world, which will not be able to have a common plan of action against global warming or how to regulate the explosive potential of AI. That’s the most dangerous outcome of all this.”

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) and the New Taipei City Government in May last year agreed to allow the activation of a spent fuel storage facility for the Jinshan Nuclear Power Plant in Shihmen District (石門). The deal ended eleven years of legal wrangling. According to the Taipower announcement, the city government engaged in repeated delays, failing to approve water and soil conservation plans. Taipower said at the time that plans for another dry storage facility for the Guosheng Nuclear Power Plant in New Taipei City’s Wanli District (萬里) remained stuck in legal limbo. Later that year an agreement was reached

What does the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) in the Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) era stand for? What sets it apart from their allies, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)? With some shifts in tone and emphasis, the KMT’s stances have not changed significantly since the late 2000s and the era of former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). The Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) current platform formed in the mid-2010s under the guidance of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and current President William Lai (賴清德) campaigned on continuity. Though their ideological stances may be a bit stale, they have the advantage of being broadly understood by the voters.

In a high-rise office building in Taipei’s government district, the primary agency for maintaining links to Thailand’s 108 Yunnan villages — which are home to a population of around 200,000 descendants of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies stranded in Thailand following the Chinese Civil War — is the Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC). Established in China in 1926, the OCAC was born of a mandate to support Chinese education, culture and economic development in far flung Chinese diaspora communities, which, especially in southeast Asia, had underwritten the military insurgencies against the Qing Dynasty that led to the founding of