On Nov. 19 1990, the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences in the US revoked a Grammy award for the first (and so far, only) time. Pop duo Milli Vanilli were disgraced after music producer Frank Farian revealed the pair hadn’t sung a single note on their multi-platinum 1989 album, Girl You Know It’s True. Frontmen Fab Morvan and Rob Pilatus were great dancers, sure, and they looked great in their oversized shoulder pads. But the duo had lip-synced their way to success. In the span of nine months, Milli Vanilli went from the world’s official best new artist to the (handsome) faces of music history’s biggest hoax.

It’s not quite a Grammy, but last month, TikToker Addison Rae Easterling was nominated for a People’s Choice award. The 20-year-old American is a great dancer, sure, and looks great in oversized gold hoops. But Easterling has also lip-synced her way to success. In her one year on TikTok, the influencer has mouthed along to songs by Nelly Furtado, SZA and Katy Perry. She now has 65 million followers, a weekly podcast and her own cosmetics line.

The big difference, of course, is that Easterling didn’t deceive anyone; she’s one of 800 million active users who mime along to soundbites on the TikTok app. But you can’t help but feel Morvan and Pilatus — who were in their mid-20s at the time — would’ve fared much better 30 years on, in the TikTok era.

Photo: AFP

Today, lip-syncing is everywhere. On TV, shows such as Lip Sync Battle and RuPaul’s Drag Race have turned the practice into a competitive art. In August, US comedian Sarah Cooper landed a Netflix special after she shot to fame mouthing along to Donald Trump speeches earlier this year. Last month, Boris Johnson’s fiancee Carrie Symonds even spent an evening judging the pantomiming talents of LGBT+ Conservatives. How exactly has lip-syncing gone from the entertainment industry’s most scandalous secret to entertainment in its own right?

When Top of the Pops hit British screens in 1964, miming was a core part of the show, used in order to maintain quality control. But artists who valued, or wanted to be seen to value, authenticity would occasionally refuse to lip-sync: Iron Maiden, Nirvana and Oasis all offered various forms of protest (the Gallagher brothers switched places when performing Roll With It in 1995). Miming was maligned by fans who felt they were being cheated, plus it had the potential to be horrifically embarrassing. In 1988, All About Eve famously blundered on TOTP when the band couldn’t hear the backing track and sat stony-faced while it played for the audience at home. They came back on the show a week later on the condition that they could play the song live.

Yet as we moved into the aughts, lip-syncing became a more widely accepted aspect of pop stardom. In his 2006 book Performance and Popular Music: History, Place and Time, academic Ian Inglis argues that MTV’s dependence on “photogenic rock singers and striking videos” normalized lip-syncing, as viewers came to expect complicated performances in live shows. In 2009, Reuters was able to report that Britney Spears, “is, and always has been, about blatant, unapologetic lip-syncing” without anyone blinking an eye. While the practice could still scandalize (see: China deeming a little girl too unattractive to sing at the 2008 summer Olympics opening ceremony, replacing her with another, lip-syncing child), by the end of the decade, non-deceptive lip-syncing was widely accepted and enjoyed.

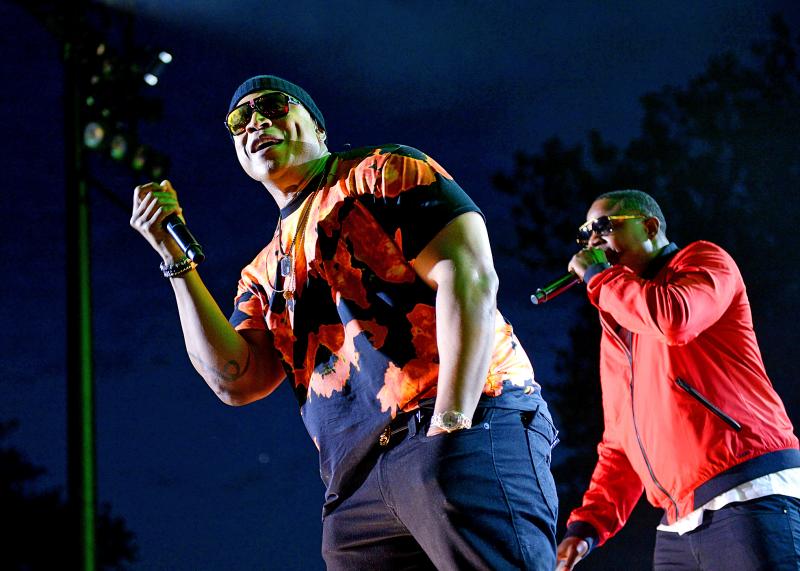

Photo: Reuters

Today, the average child in the US, UK and Spain spends 80 minutes a day on TikTok, where lip-syncing reigns supreme. The most popular video on the app, with more than 40 million likes, sees 23-year-old Filipino-American Bella Poarch mouth along to M to the B, a diss track written by a Blackpool grime MC in 2016. It’s an unlikely pairing — Poarch has the wide, innocent eyes of a Disney princess, M to the B was written by then-16-year-old Millie Bracewell, who was engaged in a back-and-forth beef with fellow teenage MC Sophie Aspin. At the height of their YouTube fame four years ago, the duo exchanged insults such as “sket”, “slag”, and “daft little dog”.

Poarch doesn’t lip-sync those lyrics in her viral hit — she sticks to the clean part of Bracewell’s song, instead mouthing, “It’s M M M M M to the B” while contorting her face over the course of 11 seconds. The clip is equally baffling and enticing — why have half a billion people watched it? Why do you find yourself watching it over and over again?

Poarch’s popularity might seem like a thoroughly modern mystery but, in fact, the Internet has always allowed lip-syncing to flourish. One of the Web’s biggest early viral hits was the Numa Numa Dance uploaded by vlogger Gary Brolsma — it’s estimated that between 2004 and 2006, more than 700 million watched him mouth the words “Ma-i-a hi, ma-i-a hu, ma-i-a ho, ma-i-a ha-ha.”

Photo: AP

Writing in 2006, Slate writer Sam Anderson argued that “amateur lip-syncing” was “liberated” by the Internet, with YouTubers attracting thousands of fans by turning “a private folk art” into a public spectacle.

Of course, anyone with a hairbrush and a mirror knows that lip-syncing is an enjoyable act, but the real question is: why do people like watching it?

“I think the appeal is often rooted in parody,” says Elizabeth Cohen, a professor of communication studies at West Virginia University, “The humor often stems from the incongruity between the person doing the lip-syncing and the person being lip-synced.”

Lip Sync Battle has attracted millions of viewers since its inception in 2015 — popular clips include Anne Hathaway licking a hammer in homage to Miley Cyrus’s Wrecking Ball and Dwayne Johnson channeling Taylor Swift by Shaking It Off. In the middle of the 20th century, the growing popularity of jukeboxes allowed drag queens to engage in identity play and make lip-syncing an integral part of their culture — last year, more than 6.5 million Brits watched RuPaul’s Drag Race UK on BBC Three, marveling as queens were asked to “Lip Sync for Your Life.”

But why is lip-syncing having a heyday now? Cohen says TikTok videos “provide a pleasant distraction from more serious and stressful things going on” — arguably, the app was born at the right time in 2016. A year later, it took over Musical.ly, a Chinese app dedicated entirely to lip-syncing, and changed culture for ever.

Cohen argues that the app allows people to foster community, which can be invaluable during lockdowns.

“Lip-syncing requires a little bit of talent but not much, so it’s something that’s extremely accessible for a lot of people to participate in,” she says.

Despite this low barrier for entry, lip-syncing can be an avenue for creativity. TikTok Trump impressionist Sarah Cooper has shot to fame in less than a year, and she isn’t alone in using lip-syncing for political satire.

Meggie Foster is a 27-year-old from Oxford who has been creating viral parodies of British politicians and celebrities since March. Foster says each short clip takes between two to five hours to make — she has to memorize the celebrity’s words, swap outfits and find the right props (such as the £5 note she wiped her tears with as Meghan Markle, or the bottle of Smirnoff she swung around as Priti Patel).

Half a year ago, Foster was a theater graduate who had just been furloughed from her sales job; now she has her own agent, and she was recently stopped by a jogger who recognized her on the street.

“It does feel surreal, but it’s been a really good launchpad for my acting,” Foster says.

Yet she hasn’t yet been able to monetize her talent, and doesn’t want to pursue lip-syncing as a full-time career.

“I wouldn’t want to be labeled ‘the lip-sync girl’ … it’s one tool in my toolkit,” she says. “There’s much more to me.”

Foster might not want the label, but plenty of others do. More than 80 percent of TikTok users have posted their own videos to the app; after Bella Poarch’s mega-viral hit, there are now 7.5 million videos featuring M to the B. Milli Vanilli even have their place — just over 200 people have created videos set to Girl You Know It’s True, lip-syncing along to history’s greatest lip-syncers.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she