Is the trash can half full or half empty?

When it comes to handling garbage, Taiwan has made tremendous progress. The proportion of waste that ends up in landfills has shrunk to less than 1 percent. Thanks to one of the world’s highest recycling rates, there isn’t enough household refuse to keep the nation’s incinerators busy.

Yet, at the same time, anyone who travels through rural Taiwan will see plenty of bottles, cans and plastic bags by the roadside. Much of this waste persists in the environment as microplastics after it degrades.

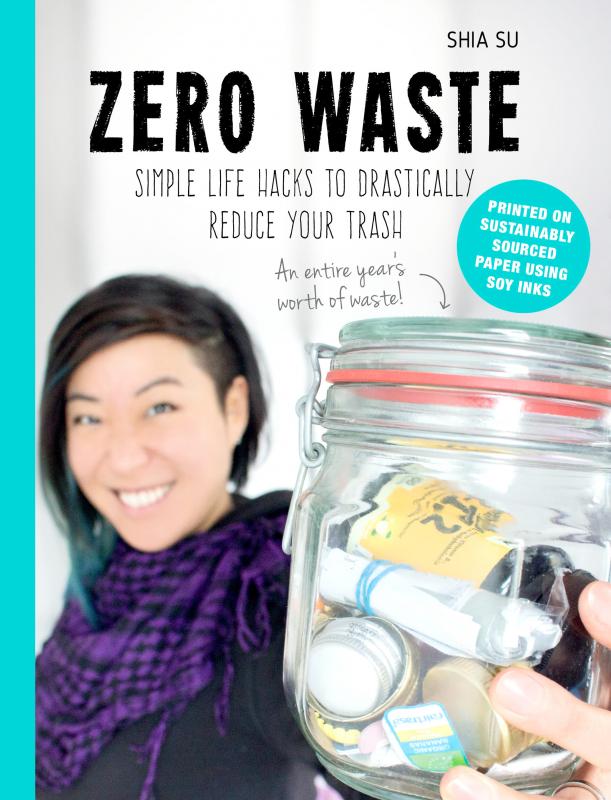

Photo Courtesy of Shia Su

“Minimizing the amount of waste we create is one way to reduce our environmental footprint,” says Shia Su (蘇小親) author of Zero Waste: Simple Life Hacks to Drastically Reduce Your Trash.

Inspired by the realization that “our wasteful ways are literally draining this planet,” Su — who was born in Germany to Taiwanese parents — and her husband, Hanno Su, gradually adjusted their consumption habits to the point where they now produce about as much garbage in an entire year as the average Taipei resident generates every few days. To reduce their energy footprint and environmental impact, the couple also follow a vegan diet, live in 10-ping studio apartment in Cologne and buy only secondhand goods.

‘ZERO WASTE’

Photo Courtesy of Shia Su

Many of the tips in Su’s book first appeared on the couple’s English and German-language Web site, wastelandrebel.com. Readers can learn about composting in the confined space of an apartment, how to make plant-based milks at home, how to freeze bread without plastic and using rye flour instead of liquid shampoo.

Zero Waste was first published in 2016 in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Since then, Su has made multiple revisions, with the German-language edition now in its sixth edition.

An English-language version appeared in 2018. Taiwan’s Cite Publishing brought out a traditional Chinese edition, titled Zero Waste: A Beautiful Life Without Plastic, Waste or Garbage (零廢棄: 不塑、不浪費、不用倒垃圾的美好生活), last year.

The changes Su has made to the book reflect not only her own learning curve, but also conditions in different countries and the appearance of new eco-friendly products.

“I’ve updated the information on zero-waste dental hygiene items, as some innovative products have hit the market. I rewrote and completely localized the book for the North American English edition myself. That wasn’t too difficult, since I was living in Canada at the time, and familiar with what was available in Canada and the US,” she says.

The different editions also list local zero-waste stores, which Su describes as “the true heroes, as they enable access to packaging-free goods.”

One such shop is Unpackaged U (U商店) in New Taipei’s Sanchong District (三重).

“As far as I can tell, what you’d find in a bin in Taiwan is similar to what you’d find in other countries in East Asia, North America and Europe. Supermarket packaging is very similar across the globe. Convenience products, takeaway food and ordering-in have become increasingly popular,” Su says.

Su has noticed that people in Taiwan cook at home less often than their European and North American counterparts. She attributes this to eating out being so affordable.

“East Asian and North American countries do have a stronger single-use culture than you find in most European countries. In Germany, both cold and hot beverages are served in real cups and glasses in most places, unless you request otherwise. In Canada and the US, it is usually the other way around, with many coffeeshops not stocking any reusable cups,” Su says.

Even though Taiwan’s night markets and bubble-tea stalls generate a great deal of single-use trash, Su says that the country is doing better than North America in one respect: “In Taiwan, disposable food containers have been made from plastic-lined paper for many years. These aren’t so bad for the environment as the Styrofoam containers which are still going strong in many parts of the US and Canada. In Germany, disposable food containers are usually made from aluminum or plastic, and there’s now a slow shift to compostable alternatives.”

On her Web site, Su writes that zero waste “is first and foremost a shift in mentality towards empowerment. In finding an open mind to try new things, we learn to challenge the status quo and tread our own path to happiness. Material things don’t make us happy in the long run.”

BABY STEPS

When the couple began their waste-reduction journey, they didn’t expect to get as far as they have — and Su advises those who aspire to a zero-waste lifestyle to take baby steps, and not dwell on what seems difficult or impossible.

“We wanted to reduce our trash and live more sustainably, so we tried one thing after another at our own pace. I never thought beyond the next step. If one approach didn’t work, I’d just try another one,” she says.

Su often speaks of the joy that comes with each breakthrough, whether it’s getting a sushi bar to put a take-out order in her reusable container rather than a disposable box, or meeting a health-food store owner who decided on the spot to begin encouraging customers to bring their own bags when buying organic rice.

Recalling the second episode, Su says, “It was then I realized things could change for the better if I just let my voice be heard.”

Her reminder to consumers that they’re not limited to what’s offered on supermarket shelves is particularly relevant in Taiwan, where every town has at least one daily, traditional market where vendors sell meat, vegetables and fruits that aren’t sealed in plastic.

Su often receives emails from readers whose minimal-garbage ambitions aren’t shared by other people in their household. She recalls that when she and her partner decided to go vegetarian “my mom made it very clear she wanted no part of it.” Two years later, when the couple went vegan and embarked on their zero-waste lifestyle, Su’s mother again expressed dismay.

Within another two years, however, her mother had begun cooking vegan dishes, refusing plastic bags when shopping and carrying her own reusable chopsticks.

“She rinses old plastic bags out and hangs them up to dry for reuse,” says Su.

Su’s mother wasn’t the only one to surprise her. Many of Su’s friends are now big fans of Meatless Monday or reusable coffee cups.

“It rubs off eventually,” she says, asserting that if everyone were to pick up a few eco-friendly habits, the impact could be huge: “I firmly believe it isn’t just a drop in the ocean. Together, we are the ocean.”

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful