OCT. 12 to OCT. 18

The Japanese government tried hard to convince Yang Chao-chia (楊肇嘉) to adopt a Japanese name, sending several agents to visit him in 1942. The outspoken political activist turned them down each time, finally deciding to flee to China to avoid further harassment.

Two years earlier, the colonial government began encouraging Taiwanese to adopt Japanese names as part of its kominka policy of fully assimilating the population. However, by the end of 1941, only about one percent had complied.

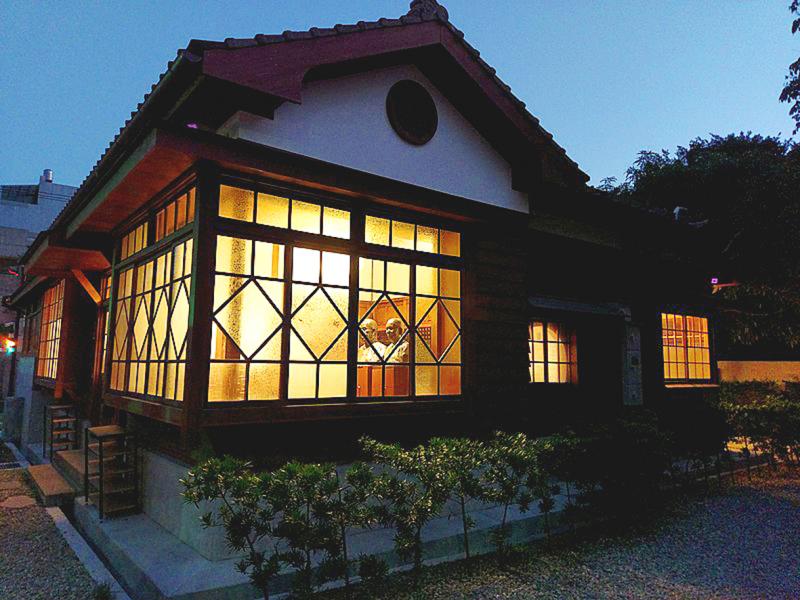

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“They hoped that I would lead by example and influence the masses. But how can I sell my soul? How can I betray my ancestors?” Yang writes in his memoir.

Yang’s strong distaste for Japanese rule permeates the entire memoir, beginning from the introduction, where he rails against the Japanese efforts to destroy Han culture and identity among Taiwanese.

“Over 50 years [of Japanese rule], we have lived like slaves and have been treated worse than livestock,” he writes. “But in such dire circumstances, did we forget [who we are]? Did we throw away [our identity]? Did we lose our dignity? I can answer with full confidence: No!”

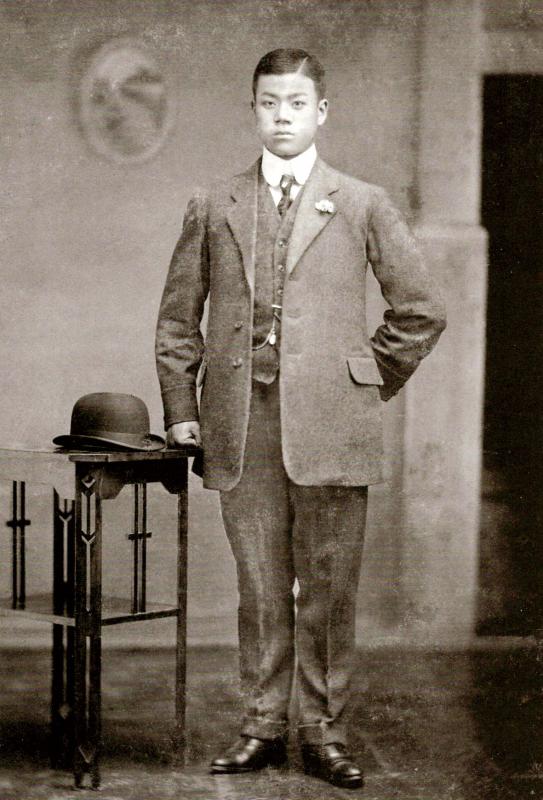

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yang had retired from activism by then due to Japanese imperialism, but just a decade earlier he was dubbed the “Taiwanese Lion” and gave his all for Taiwanese autonomy, finally achieving limited results when the Japanese allowed partial elections in 1935.

Yang’s journey to China was not smooth as he was captured by the police in Japanese-occupied Manchuria and detained for 16 days. Despite opposing the government for much of his adult life, this was his first time in jail. He was released due to his connections, and settled with his family in Shanghai. He moved back to Taiwan after World War II.

‘JAPANESE PUPPET’

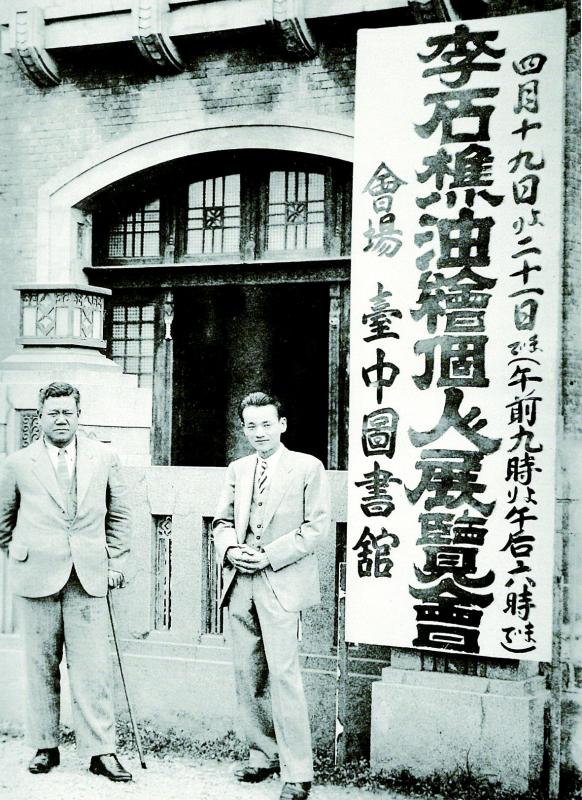

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yang was born on Oct. 13, 1892 to a farming family in today’s Chingshui District (清水) in Taichung City. He was old enough to remember fleeing into the forest with his entire village in 1895 as the advancing Japanese army barreled through the area. Fortunately, nobody was harmed, although the soldiers slaughtered the livestock and raided the rice jars.

“But we heard all sorts of terrible news from other areas. In one village, all the young men were conscripted into the army and never returned. In another village that tried to resist, the Japanese massacred [all of its people] and burned it down ... Although nothing happened to us, we were very cautious and afraid of these ‘foreign barbarians.’”

When he was six years old, he was adopted by the richest family in Chingshui, also surnamed Yang.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“When I was four, I was forcefully cut off from the motherland with the entire Taiwanese population, and when I was six, I was forcefully cut off from my birth parents. As a child, I had already experienced the double trauma of loss of country and loss of family,” he writes.

Although Yang ran away several times, it was because of his new family that he received a formal education and was able to study in Japan at the age of 15. He returned to Taiwan in 1914 and worked as a teacher in his hometown. At this time, he was still happy to work with the Japanese, and served as a local official, although he was known for frequently challenging the government for the rights and welfare of Taiwanese.

In 1920, Yang became the chief of Chingshui Street (a Japanese-era administrative unit), but he called it a “puppet position” under the guise of “fake autonomy” as control was still in the hands of the Japanese. He realized that the only way to change things was to establish an elected Taiwanese assembly and hold direct elections for local positions, which coincided with the ideals of rising activists Chiang Wei-shui (蔣渭水) and Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂).

The various passive resistance movements stoked the fire in Yang’s already burning heart, and he threw himself into the heat of the action despite his position.

“I’ve awakened! The entire population of Taiwan is also awakening!”

AUTONOMY ACTIVIST

Yang’s first act of public defiance came in 1925, when activist Tsai Hui-ju (蔡惠如) insisted that he participate in the sixth petition to the Japanese Imperial Diet to establish a Taiwanese representative assembly. This was against the rules as a public official, but he set out for Japan with the delegation anyway. Although the effort failed again, the group was given a hero’s welcome by a cheering crowd when they landed in Keelung. There was no turning back for Yang.

Over the next decade, Yang tirelessly fought for Taiwanese self-rule. While the resistance movement split into leftist and rightist factions, Yang supported the rightists, believing that leftist ideals would tear the movement apart since most of its leaders were wealthy, highly-educated landowners. For Yang, Taiwanese autonomy should be the sole goal of the movement.

In 1930, he helped form the Taiwan Local Autonomy Alliance (台灣地方自治聯盟), which grew quickly and attracted large crowds during its speeches across the colony. Five years later, the Japanese finally allowed the public to elect half of Taiwan’s city and township councilors, and the alliance fielded many candidates — all but one made it to office.

Yang deemed the election a success, writing that it went fairly and orderly.

“Our hard work over the past five years has not gone to waste,” he says. “We have created a new environment for the people and society of Taiwan, and set a good precedent.”

However, this celebration was short-lived as Japanese imperialism was growing. The government launched the kominka movement in 1937, its first move banning Chinese in all newspapers. Yang and Lin traveled to Japan that June to plead for the new cabinet to reverse its policies, but things took a turn for the worse when Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China on July 7.

The Alliance disbanded in August, and Yang retired from activism to focus on his family, whom he writes that he had neglected for the previous seven years.

“For the people of Taiwan, I helped them obtain what nobody had been able to achieve; I did what nobody dared to do, and what nobody was willing to do. I think that I did not let Taiwan and its people down.”

Although Yang clashed with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) at first over Taiwan governor-general Chen Yi’s (陳儀) misrule, he later supported the government and seemed to be happy enough that it allowed a certain degree of direct local elections without the heavy restrictions that the Japanese placed on the 1935 votes.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on