With calls to grant political asylum to Hong Kong dissidents, Taiwan’s refugee law has been in the spotlight recently. Exhibitions, workshops and presentations on the issue have been organized by NGOs and activists. However, absent from the discussion has been an examination of the role of refugeeism in shaping contemporary Taiwan.

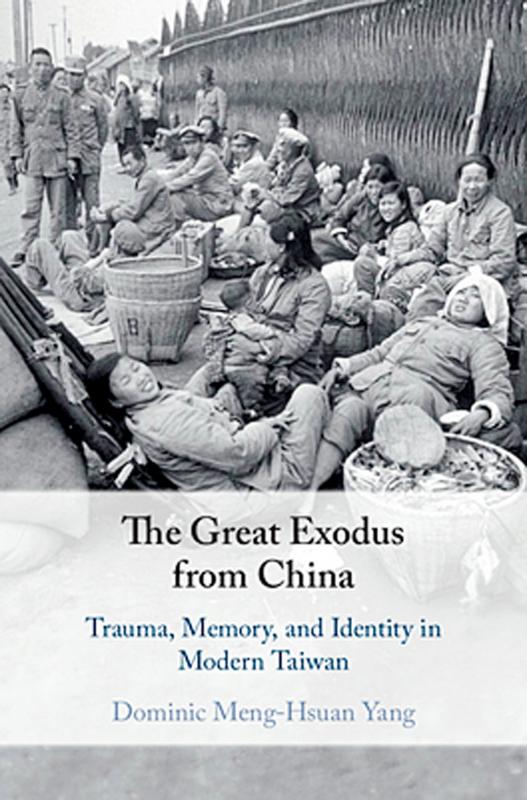

A recent exhibition revealed the historical parallels. Among the photographs taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson in China between 1948 and 1949, currently on display at Taipei Fine Arts Museum, images of the mass displacement caused by the civil war feature prominently. From well-to-do legislators to ragged soldiers, all walks of life are represented. While most refugees ultimately remained in China, many fled to Hong Kong, and roughly a million arrived in Taiwan in what Dominic Meng-Hsuan Yang (楊孟軒) describes as “a human tidal wave … a gigantic influx of people.”

Coinciding with the exhibition is the release of Yang’s book, The Great Exodus from China: Trauma, Memory and Identity in Modern Taiwan. This timely monograph underscores the social diversity of the refugees. Aside from military and high-ranking officials who had landed in Taiwan at the end of World War II, the earliest arrivals, Yang explains, were the more affluent and influential types — those who could leverage money and status to secure prime position on planes and boats.

Some of these bigwigs balked at being called refugees or exiles. In one interview, an “urbane and affable” ex-customs official was agitated by Yang’s questions. This wealthy octogenarian insisted he and his wife were “not your typical refugees.” They had arrived in Taiwan literally under their own steam after he had chartered a boat for his family, 20 of his subordinates and their families. The crossing, he stressed, had been made with “great comfort and full amenities provided.”

Yet, when Yang pointed out that, luxury notwithstanding, this had been a forced migration, the former civil servant was incensed. Repeating his claim that it had been a voluntary relocation, he stormed out of the room, slamming the door. Mortified at having caused offense, Yang reflected that the anger and denial he had witnessed was borne of humiliation at the disintegration of everything this Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) stalwart had held dear.

At the other end of the social scale, Chiang Si-chang (姜思章) was one of more than 13,000 male residents of the Zhoushan Islands pressganged into the KMT army and removed to Taiwan in May 1950. Meng’s description of wailing relatives wrestling with soldiers as their loves ones were ferried away is eerily reminiscent of Cartier-Bresson’s photographs of KMT “recruitment” in Beijing in December 1948. In one image, which ran in the Jan. 3, 1949 issue of Life magazine, a woman is shown pleading with a soldier. “Consolation,” read the accompanying caption, “is all one mother finds in search for her son.”

But whereas Cartier-Bresson’s photographs capture the anguish of an exodus unfolding, Yang focuses on the impact on the displaced and, in turn, Taiwanese society. He resists what he sees as a Eurocentric “single-event model,” of trauma stemming partly from the notion of the Holocaust as a “limit event” and a “universal symbol of the global human-rights/memory culture.” Instead, Yang argues that the post-World War II migrations to Taiwan resulted in “a multi-event trajectory of repeated traumatizations” based on a perennial search for identity and home.

Chiang’s case is instructive. Kidnapped as a 15-year-old, he remained embittered toward the KMT. After three years in prison for insubordination and an attempted escape in the 1950s, Chiang eventually managed to sneak back to China via Hong Kong, reuniting with his family in 1982. Cofounding the Veterans Homebound Movement (老兵返鄉運動) in 1987, in an unlikely alliance with the fledgling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), he became instrumental in getting then-president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) to lift the ban on Taiwan residents visiting China.

Yet, while Chiang Si-chang had dreamed of this return for decades, like most first-generation waishengren (外省人, “Mainlanders,” or people who fled from China with the KMT after 1949 ), he showed no desire to resettle. Taiwan, after all, was his home. And Chiang was among the few to find his birthplace largely intact with a loving family waiting for him. Most were not so fortunate.

Central to Yang’s thesis is that these “homecomings,” which at best could never match expectations and, at worst, were devastating shocks to the returnees, compounded the trauma. Villages were unrecognizable, ancestral shrines and tombs destroyed; where families remained, avaricious relatives jockeyed for the largesse they believed their “Taiwan compatriots” were duty-bound to dispense. In most cases there were no hooks on which the prodigal sons could hang their nostalgia.

The second “homecoming” to a Taiwan that was undergoing rapid democratization and with it, for the first time, open discussion about the White Terror period, was a further blow to the waishengren. Suddenly, they were branded colonizers, complicit in the abuses of Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) dictatorship.

Yang’s greatest achievement is to show that, rather than accomplices, many of these people were victims. Through analysis of such factors as the disproportionate crime and suicide rates among waishengren in the early years, the psychological effects of rootlessness and isolation on laobing (老兵, elderly veterans) and the mnemonic strategies that refugees employed to cope, Yang elucidates a prolonged trauma comparable to contemporary humanitarian crises.

In his epilogue, Yang admits to ethical concerns over his “subject position.” As a Canada-raised “1.5 generation” Taiwanese, he returned to Taiwan to research an MA thesis on the 228 Incident. Stoked by personal grievances, resentment toward “Mainlanders” informed this work. Gradually, however, Yang acquired “a mediated and historically informed empathy for waishengren.” This helped create “some kind of critical distance from the fidelity to my own family trauma.”

In adopting what historian Dominic La Capra’s calls a “working through” approach to trauma, Yang provides a sensitive and balanced appraisal of the waishengren experience in Taiwan. More broadly, The Great Exodus is a timely reminder of the importance of compassion for refugees everywhere.

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

A six-episode, behind-the-scenes Disney+ docuseries about Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour and Rian Johnson’s third Knives Out movie, Wake Up Dead Man, are some of the new television, films, music and games headed to a device near you. Also among the streaming offerings worth your time this week: Chip and Joanna Gaines take on a big job revamping a small home in the mountains of Colorado, video gamers can skateboard through hell in Sam Eng’s Skate Story and Rob Reiner gets the band back together for Spinal Tap II: The End Continues. MOVIES ■ Rian Johnson’s third Knives Out movie, Wake Up Dead Man